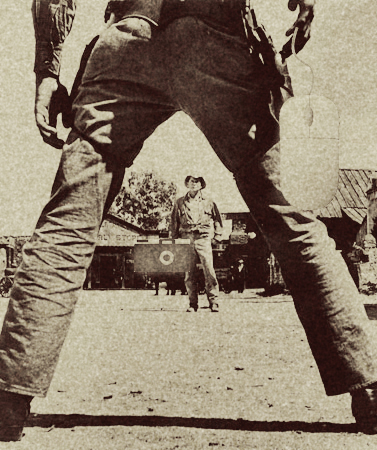

aNewDomain.net — On the Internet, image rights and usage are a little wild west-y in terms of a copyright showdown. Think of it this way: You’re like Black Bart — knees bent with your hand hovering over your holster ready to appropriate an image. And at the opposite end of the square is the sheriff, the guy who created and owns the image.

Once an image is transferred into a commodity, it becomes a fragile thing. Even if you know what you’re doing, your pictures can be the object of a bitter showdown.

Image credit: Viki Reed

There is No Artistic Merit to a Phonebook …

But it’s my image, you might say. Surely I own the rights to it? Yes you do, said Michael Grecco in an article at EditorialPhoto.com. And maybe you don’t.

In most cases the photographer is the copyright holder. The exceptions are employees where the company owns the work, and photographers who have signed a work-for-hire agreement. Since the work is copyrighted at the moment of capture, work-for-hire agreements are not enforceable unless they are signed BEFORE the capture of the image.”

Oh, and the photo must have stand-alone artistic merit. Grecco clarifies:

A copyrightable work must be … an ‘original work of authorship.’ The example that is often given is that you can not copyright a phone book. There is no artistic merit to a phone book. There must be some sort of value to it, however minimal … You can NOT copyright a concept. The look and feel of the image is what is copyrightable.”

License and Registration, Please, Ma’am …

True dat, the image is yours upon shutter release. Without the work being registered with the U.S. copyright office, however, you’ll find that violators don’t have much to fear. The burden is on the artist to prove the value of their work. As Grecco says, “Without registration there is no mechanism for triple damages.” Don’t forget you’re paying the lawyers to fight for you, too. Someone using your image unlawfully has better odds at winning than a gambler does at the Borgata Casino. It’ll cost you more to get your ounce of flesh than it would cost the thief to license it up-front.

Carolyn E. Wright. Image credit: PhotoAttorney.com

Okay, I’m Gonna Be Sick …

Now you know. You perused TinEye and Google Images and found one of your shots on someone’s website or magazine article. Black Bart took his shot. You’re not dead yet, but what do you do? How do you find an attorney specializing in all things photography? Carolyn E. Wright, a fantastic photographer and lawyer whose site PhotoAttorney.com is THE first stop for photographers who start getting serious about their intellectual property, told aNewDomain.net:

The best way to find a lawyer is to get references. Talk with other photographers and business colleagues to solicit their recommendations. You may be able to review an attorney’s credentials at LexisNexis Martindale-Hubbell (a national listing of lawyers at www.martindale.com). Just as with doctors, many lawyers practice or specialize in certain areas, so it is best to find one who has experience with your particular issues. For photographers, issues can range from copyright and trademark to employment and contract law. While you may hire one attorney to help you with certain needs, that attorney may refer you to another lawyer for help in a different area of practice. When you hire your lawyer, make sure that the agreement is in writing and that the agreement specifies what work is to be performed.”

She also makes it clear that keeping someone from crossing the line is your duty:

“It’s not Getty’s, Google’s or Bing’s responsibility to protect photographs! Instead, photographers must do everything possible to protect their photographs. The first step is for photographers to learn as much as they can about the issues related to copyright.” For more information, check out Wright’s article, “Five Things You Can Do to Protect Your Online Images.”

Wright continues the good fight with an article on Naturescapes.net called, “Help! I Found an Infringement! Now What do I do?” She admits that the documentation procedure for returning fire is more complex, but it is as crucial as the registration process. Ultimately, you have a couple of options. You can keep your response simple and request a credit be attached to your photo. Or you can escalate things further by filing a Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) Takedown Notice. Once again, Wright has a lot to say about your options in an article called “Using the DMCA Takedown Notice to Battle Copyright Infringement.”

Image credit: John C.H. Grabill and Viki Reed

A New Sheriff’s in Town

The Digital Millenium Copyright Act was enacted in 1996. It was the Clinton Administration’s attempt to address copyright issues specific to the Internet. Back then, the world was a much simpler place with just Yahoo, AOL, Prodigy and Alta Vista.

The comparison to a creative high noon is accurate. Today’s high school graduation class is older than the first effort to organize the digital wild west. (Fortunately a work at this time doesn’t have to be registered in order for you to take advantage of the DCMA.)

Sometimes the law is a renegade. For example, attorneys who rightly and wrongly practice hardcore copyright assertion. Matthew Chan, a self-professed web tummler, publisher, speaker and consultant, has declared war on lawyers who are “technically right but morally wrong” by chasing every registered copyright violation they can find and extorting money from the violator.

Chan mentions Getty Images almost exclusively on his website’s discussion forums. One can imagine that he “technically violated” a lot of Getty Images copyrights.

Despite being a stomping baby about his own wrongdoing, there is a kernel of worry about which direction tort is going when we’re still in a gunslinger’s paradise. (For examples, check out Chan’s obnoxious forums at his website.)

Chan is not alone, however. In 2011, WebCopyPlus! (a content provider offering SEO/keyword rich copy) used an image without paying. The story of how this growing company had to cough up $4,000 for a $10 image license emphasizes the power of registration.

WebCopyPlus! had a stock photography account, but one of its indie-acting copywriters snagged a shot from Google Images. Seven months after using the image on a client’s site, WebCopyPlus! received a cease-and-desist letter from an attorney.

The photographer’s lawyer skipped the I-want-a-photo-credit request. Nor did he invoke the DMCA Takedown Notice. Instead, he shot clear through the heart by issuing a cease-and-desist letter. The next step was a lawsuit. The photog wasn’t happy with mere removal of every remnant of the picture from servers, sites and client pages: he wanted $4000, too.

Counter offers were rejected. The unintentional outlaw had no bullets left.

Now a client was entangled in an ugly legal mess and the attorney and photographer had a copyright registration number which entitled them to triple damages. Naturally, the photographer was within his rights to demand more from WebCopyPlus! but the whole thing felt a little bit like opportunism, like those skeevy commercials you see on TV late at night: “Have you ever been hurt in a traffic accident? Call us now. We’ll get you what you deserve!”

This is a concern with merit. In May of 2013, The Electronic Frontier Foundation, along with the Digital Media Law Project, filed a brief in federal court urging protection for victims of abusive DCMA Takedown Notices. Ultimately, it’s your bad, no matter how ugly it gets.

Okay, I Won’t Use ANY Images, I’m Scared!

It’s only scary if you go down the wrong road. The right of way isn’t so treacherous. Depending on the circumstances, free images are available for your professional and personal use.

First the toll roads: these are images that come with terms and/or a price. In an article on her site called “Copyright Fair Use and Online Images,” attorney Sara F. Hawkins beautifully defines it thusly: “Stock photo services require you to pay for a license, creative commons licenses confer the right to use an image under certain circumstances and public domain images are not subject to copyright in the first place.”

Wherever you find an image, take a trip down the rabbit hole to find the original source and verify its terms of use. If asked, many copyright holders are happy to allow bloggers and non-commercial entities to use an image with a credit. You must confirm permission to use any image. These are hangin’ words.

Well, Except For …

Fair use: it’s the term meant to acknowledge the copyright holder while protecting the public’s interest to know. If you have questions concerning fair use, Wikipedia covers the minutiae serviceably. The Electronic Frontier Foundation defines fair use by what it isn’t — as a limitation on copyright instead of another version of it.

The fair use saloon: a joint where everyone is okay with the copyrighted image being used. Product review, criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship or research are all forms of fair use.

According to APhotoEditor.com, you still need a top-off: “Always include the photographers name and links to both the image(s) you are writing about and their portfolio in your story or in the caption to the image. The destination of the anchor link for the image should be the page where the image was found (most blogging platforms have the anchor link to a larger size image so this has to be changed manually).”

There are finer points involved with fair use that include whether the copyrighted work was used to create a new work, was published versus not, etc. Be clear on how you view an image you’re using.

Public domain: start with PDImages.com for a list of public domain image resources. Images become public domain if their copyright has expired or if they were never eligible for copyright in the first place. For work created after 1978, copyrights lapse after the death of the creator plus 70 years. But copyright law is tricky and is characterized by many subtle points. Be sure to go directly to the official U.S. government site if you need copyright clarification.

Holster your sidearms, Black Bart. If you play it right, nobody has to get hurt.

For more information:

- Refer to PhotoAttorney.com‘s no-gray-area lay down of what a copyright holder owns.

- The easiest way to copyright your work is via electronic registration at the U.S. copyright office. However, this process (which costs $45 per filing) limits you to registering images “within the same unit of publication.” For solid footing, it’s best to register the old-fashioned way, via paper. This will allow you to cover your pictures as a “group registration of published photographs.”

- For a definitive how-to guide to help you navigate the registration process at the Electronic Copyright Office, take a look at Carolyn E. Wright’s step-by-step tutorial.

- For the paper trail version, photographer Chris Martino does an equally thorough job.

Based in New York, Viki Reed is a senior photographer and pop culture commentator at aNewDomain.net. She’s worked with SubBrilliant News, Anti-Press and Thewax. Check out her work at vikireedphotography.com and email her at Viki@aNewDomain.net or viki@vikireedphotography.com.