aNewDomain — I don’t understand dancing. It doesn’t move me and I don’t move. But my family likes this show, this dance contest. So I’m stuck with it. What I notice most are the stories.

aNewDomain — I don’t understand dancing. It doesn’t move me and I don’t move. But my family likes this show, this dance contest. So I’m stuck with it. What I notice most are the stories.

Sometimes they’re stories of privilege, mostly they’re stories of overcoming. Illness, loss, poverty. A guy gets recruited by gangs but turns to dance as a way out. So many people seem to aspire to be great dancers. But why? What’s it for? What good is it?

Sometimes they’re stories of privilege, mostly they’re stories of overcoming. Illness, loss, poverty. A guy gets recruited by gangs but turns to dance as a way out. So many people seem to aspire to be great dancers. But why? What’s it for? What good is it?

Do we need more dancers? Or do we need more engineers, climate scientists, ecologists, community organizers? Or is there a usefulness to the useless?

Society has practical needs. But we don’t have television shows about altruism or fixing our real-life problems, like ending police militarization and systematic racism. We have shows about singing and dancing.

So, what is it all for?

Zhuangzi wanted to know. Here is his story of the useless tree. It lives to a ripe old age because it has no practical value. Maybe the most fundamental question we are capable of asking is: What are people for? And what is the purpose of being alive?

Are we here to make a difference?

Are we here to make a difference?

People sometimes like concrete answers to such questions. Governments, corporations, and religious institutions are happy to provide them. A recent recruiting ad for the U.S. Army asks what you will do to make a difference in today’s world. Is that what we’re for – to make a difference? To make the kind of difference soldiers make?

I say, be wary around people with easy answers to hard questions.

What are we for?

So often the dancers on this show are there because they didn’t have any other really attractive options. Columbia University psychology professor Carl Hart is making waves in the addictions study community in his research with crack addicts. His premise is this: Offered attractive alternatives, both people and non-human animals make unexpected choices about drugs – even those we would diagnose as dependent using the DSM.

Given a choice between $5 and a dose of crack worth more, crack “addicts” choose the money about half the time, Hart’s studies show.

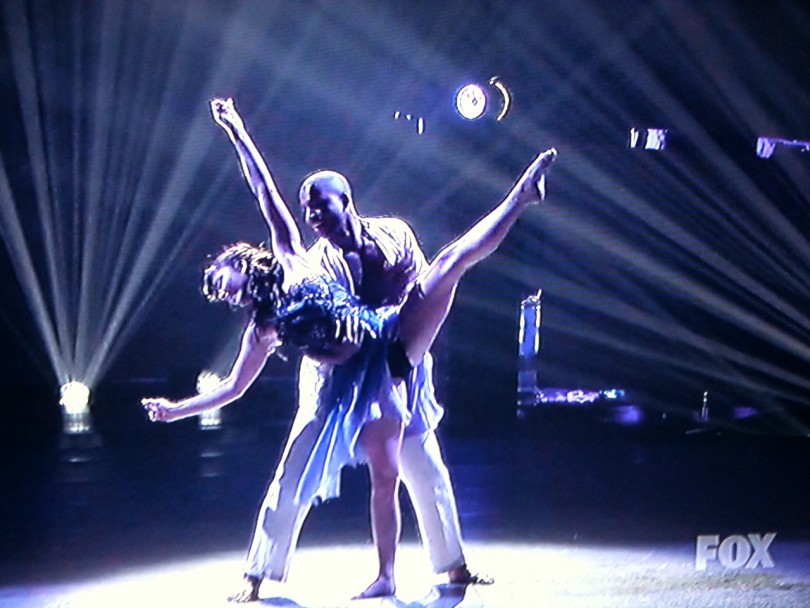

I’ve seen dancers working crowds on the street, and evidently making enough tip money to get by. But I’ve also seen them expressing something. Sure, it could be expressed in other venues, but who would listen or read or look? People stop to watch an arresting dancer; they stop to see something of beauty and pain.

I’ve seen dancers working crowds on the street, and evidently making enough tip money to get by. But I’ve also seen them expressing something. Sure, it could be expressed in other venues, but who would listen or read or look? People stop to watch an arresting dancer; they stop to see something of beauty and pain.

Doesn’t real beauty always involve some pain?

In his preface to A Call To Arms, Lu Xun writes this tale apparently of despair and realistic hope. Only four lines are pertinent here, but this passage contains many bad omens and shadows of grief, loss:

“What is the use of copying these?” he demanded inquisitively one night, after looking through the inscriptions I had copied.

“No use at all.”

“Then why copy them?”

“

For no particular reason.”

Lu Xun sits alone in his room overlooking a tree used for suicide. A useful tree, if suicide itself is of any use. He is critical of his own society, his own culture. He urges modernization. But he is aware of Zhuangzi and all the others. He knows about the useless tree as he overlooks this useful one, and tells his friend, “No use at all. For no particular reason.”

He’s translating Dostoevsky. He also does Nietzsche and several others. He knows about futility and despair, and he knows about beauty and pain. And the dangers of false hope, turning one’s back on the reality of the situation.

I can almost get into the dancing. Sometimes it tickles faintly at the place where I keep my emotions locked up in the back of my head. I can see something in it, something in the uselessness of it.

Once I gave a friend a gift, a chess piece I had carved by hand out of a piece of wood. She said, you didn’t have to do that. I was 19 years old then, so young and naive, but in some ways I saw much more clearly then than now.

I said: But what good is it to do only those things you must?

Dance on, you useless people, you cast-aside, despairing ones.

I hope we never find a use for you.

For aNewDomain, Jason Dias.

Image one: thesceniclife, All Rights Reserved.

Image two: worldofstories.net, All Rights Reserved.

Image three: dema.az.gov

Image four: “Noeud de pendu en ficelle” by Medjaï – Own work. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons