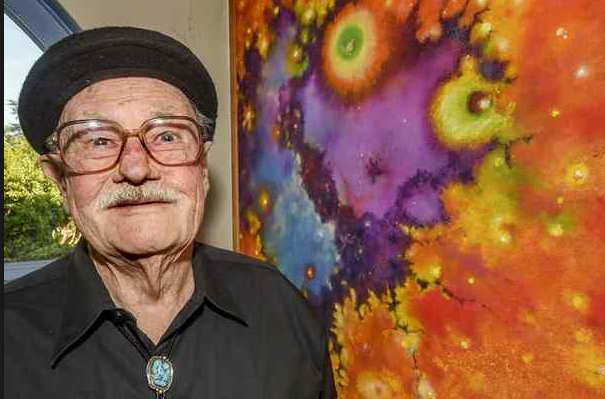

aNewDomain – The legendary astrophysicist Richard Davies is gone, I found out today.

aNewDomain – The legendary astrophysicist Richard Davies is gone, I found out today.

He was 95.

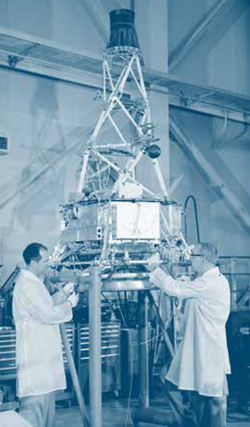

I wasn’t surprised, of course, to find that much has already been said about his long, productive scientific career at Caltech’s NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratories. After all, he led the effort to put America’s first satellite in orbit, just 84 days after Russia’s Sputnik got there. That was just one of the critical accomplishments of his long and storied career as a leading Cold War era physicist.

But I was surprised to find that no one noted the passing of the era to which he belonged. It was an era that helped define a glorious age in American science, the era of Beat Science.

Like his partners in crime and fellow beat scientists Richard Feynman, Al Hibbs, and Gus Albrecht, Davies was deeply influenced by the hipster Beat Generation movement of his youth.

These were gutsy scientists who were as home with theories and equations as they were with painting, poetry and the vagaries of social justice. They made science their art.

Science reached intense and fertile creative heights during the years they led it.

As perhaps the last surviving Beat scientist, Davies’ passing now marks the end of that era.

Here’s what you need to know about it, and what we all should remember.

When Beats met science

Beat scientists were a product of a unique time and space in American cultural history.

They were musicians, poets and writers. And artists. That was what Davies was. He was a painter, and a great one.

As a young engineer working with Davies in a JPL wargaming project in the mid eighties, Davies fascinated me with that mixture of extreme artistic talent and towering scientific accomplishment.

It was clear to me even then that Davies was of a breed that was fast becoming extinct. And so it has.

Peaceniks and physicists

Davies friends and colleagues Feynman, Hibbs, Albrecht and the artist Jirayr Zorthian were all Beat Generation peaceniks.

Like the Hippie Generation that followed theirs, they were morally and philosophically against the idea of war.

Yet they were practical about it and preferred to work for peace from the inside.

I remember that Davies lived by the ancient adage of si vis pacem, para bellum.

That is, if you want peace, prepare for war.

In Davies’ long career, our wargaming project at JPL in 1980s was but a tiny blip. That simulation went on to become a central training tool for the Joint Chiefs of Staff. They used it to train theater-level commanders for nearly 30 years. That’s a long, long life for a simulation.

Davies had no interest, he said, in working on a weapons program. But wargaming? Perhaps by helping to prepare for war, he could help at least limit the carnage. Davies’ understanding of the horrors of war were not theoretical. He flew 30 combat missions during World War II, experiencing plane crashes and the deaths of friends and colleagues.

Davies had no interest, he said, in working on a weapons program. But wargaming? Perhaps by helping to prepare for war, he could help at least limit the carnage. Davies’ understanding of the horrors of war were not theoretical. He flew 30 combat missions during World War II, experiencing plane crashes and the deaths of friends and colleagues.

That particular war game saved American soldiers lives in two wars through better training of their top commanders and might have possibly saved some enemy soldiers’ lives as well.

This is where his head was at, in those days.

Cool, hip and dangerous

The thing about Davies, Feynman and the rest of the Beat scientists was — they were kind of hip.

And to the rest of the world — especially their superiors — they were effectively dangerous.

Their bosses, after all, had had little control over where any one of them would end up or what they would do.

There was absolutely nothing nerdy about Davies and the other pioneering Beat scientists and artists in his group. And there was certainly nothing predictable about them.

[mks_button size=”large” title=”READ Here’s Elon Musk’s Plan to Colonize Mars ” style=”rounded” url=”https://anewdomain.net/elon-musk-mars-spaceship-colony-plans-full-text/” target=”_blank” bg_color=”#8224e3″ txt_color=”#FFFFFF” icon=”” icon_type=”” nofollow=”1″]

They practiced science as an art, an intense and rigorous art. It was the perspective they brought to everything, actually.

Their devotion to it wasn’t slavish or fed by some kind of outsized ambition. Despite this — and, perhaps, because of this — they went on to collect numerous Nobel prizes.

They worked hard, alright. And they played just as hard or harder.

They worked hard, alright. And they played just as hard or harder.

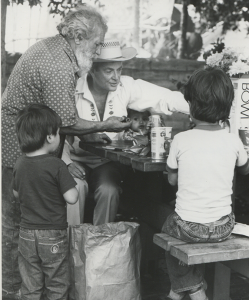

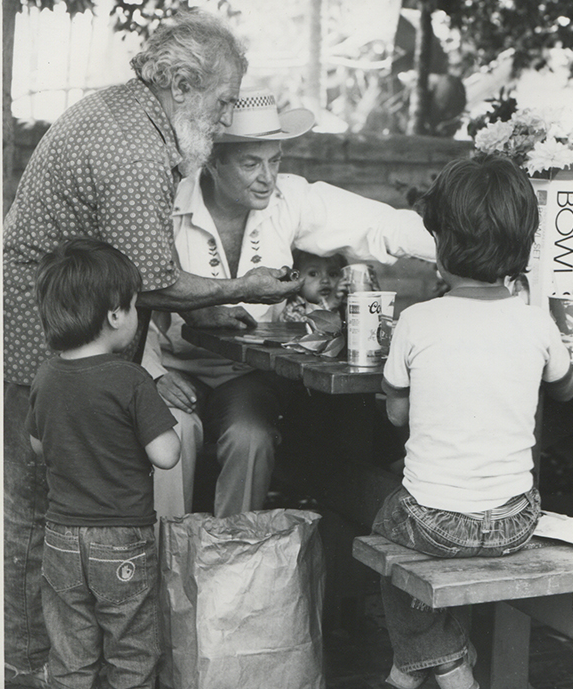

The rowdy parties they hosted at Zorthian’s ranch in Altadena were the stuff of legend (adjacent).

Once, while Charlie Parker was performing, riled up guests started tearing off their clothes off.

Feynman, Hibbs, Albrecht and the rest also organized what they called their Sunday affairs, which were weekly concerts over at Chilao Flats, on the Angeles Crest Highway.

Featuring classical, jazz and hybrid performances, these events were built around visual art, too. During intermission, they exhibited lots of art — theirs and that of their friends — and Zorthian would typically lead an arts discussion that touched on it all.

The photo above, by the way, was taken at a Zorthan bash in 1961. That’s another shot from the same party, below.

When scientists were rockstars

These days, in programs like The Big Bang Theory and other media, the brightest scientists often are portrayed as hapless eggheads and out-of-touch, irrelevant social outcasts.

Typically, they are depicted as trivial people, losers whose good work is doomed to falling in the hands of a cold, hard and largely amoral corporate machine.

That wasn’t the reality of Davies and the other Beat scientists at NASA and JPL.

Back then, NASA scientists were like rock stars. And they definitely got the rock star treatment. They were celebrities in every sense of the term.

They were at once heroes of American science and American culture.

Scientifically, of course, they had chops. Take Davies. He could count among his long list of engineering feats the fact that he was a key member of the team that built the United States’ first satellite, Explorer I.

It was a monumental feat of engineering that managed to rapidly finish a satellite and get into orbit a mere 84 days after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik.

“The Sputnik (launches) cut through the core of the entire nation,” remembered Richard Davies at a NASA reunion of its greatest space scientists a few years back. “The Soviets were not supposed to be ahead of us.”

After the Navy’s unsuccessful launch of its Vanguard rocket in December 1957 — it was a direct response to the Sputniks— JPL and the Army got the US’ go-ahead to develop Explorer.

Davies worked on spacecraft dynamics and post-launch data analysis.

“There was excitement. We were chafing at the bit,” Davies added. “We had been working on solid rocket stages for many years.”

“We experienced numerous failures in the beginning [of the space program],” he said . “But these disappointments didn’t dampen our desire to try again.”

“I’ve seen so many people with souls damaged by the unending sameness of their work,” Davies added. “But we were lucky. Our souls were lifted by the very nature of our endeavors.”

“I’ve seen so many people with souls damaged by the unending sameness of their work,” Davies added. “But we were lucky. Our souls were lifted by the very nature of our endeavors.”

Those were heady times. But as the 1970s wore into the 1980s, NASA grew into a slow-moving, aging bureaucracy.

And they presided over that, too.

The Challenger Disaster

NASA’s transformation from high-flying revolutionary to big, fat, slow government bureau was tragic for anyone who remembered the glory days.

The aging Beat scientists were known to grouse about the way NASA decision making had evolved. It was often clouded by political expediency that left science and sometimes even safety behind, they complained.

This became tragically evident one winter day in the mid 1980s. On Jan. 28, 1986, Davies and the rest of us in our group at JPL gathered around a TV in a co-worker’s office. Inexplicably, the Challenger had exploded after launch, killing everyone onboard.

We watched the news unfold silently. Suddenly, ABC News anchor Peter Jennings broke into say that NASA was about to make a statement about the tragedy.

Most of us had no idea who the NASA officials were who began speaking. But Davies did. Suddenly, Davies unleashed his trademark stentorian voice:

“Those bastards!,” he boomed. “I knew it!”

Not long afterward, Feynman was appointed to the Challenger investigation committee. JPLers like Davies were more than happy to arm him with boatloads of information about the Challenger’s design and NASA’s space shuttle program.

The investigation culminated in Feynman’s publicly revealing that the shuttle’s O rings were to blame for the explosion.

Lest anyone claim they couldn’t understand the explanation, Feynman famously dunked a set of model O rings in a glass of ice water to show how brittle they became when cold. Those brittle, cracking O Rings were the reason Challenger exploded.

Someone would’ve caught this back in 1950s and 1960s, when NASA was a lean, fast-moving operation filled with its share of hip Beat scientists.

Those days were so over.

Those days were so over.

Addicted to the system

Davies was a Caltech student in the 1940s when he decided to enlist in the Army Air Corps.

He flew 30 combat missions over Germany as a navigator and reconnaissance officer, winning the Distinguished Flying Cross. He often described the experience as “My year of living dangerously.”

And when he was free to go home and be safe again, Davies re-enlisted, explaining to friends that he was “addicted to the action.” He later explained that his war experiences were the reason he never worked on a weapons system.

After the war ended, Davies met a Welsh grad student in a London Library. He fell in love with and married Gwenda, who was also an accomplished artist.

Once married, the pair made their home Altadena, where Gwenda taught generations of children at art workshops.

Gwenda also introduced her husband to the Los Angeles painter John Altoon, who launched Richard Davies’ career as an artist.

In addition to the physics and the painting, there were marathons. A dedicated runner, Davies was forever training for marathons, an activity Feynman engaged in, too. (In fact, it was during a marathon training session that Feynman discovered the cancer that eventually took his life.)

As he grew older, Davies kept up his marathon training. At 54, he was a nationally ranked age-group marathon runner, coming in with a 2:50 marathon time.

He ran regularly in such races well into his 60s until he finally gave it up.

But he never gave up his art. Davies spent his retirement years working as a painter.

As you can see from images of his paintings throughout this post, he particularly focused on pointillist works that represented astronomical bodies like spiral galaxies, with each star appearing as a dot of light among countless others.

He exhibited at McGinty’s Gallery at the End of the World in Altadena and at the Armory Center for the Arts.

The beat goes on

I find it telling that Davies rejected the “greatest generation” accolade. He just didn’t believe that those born after the Great War were the “greatest generation.”

But Davies was a card-carrying member of the Beat Generation to the end.

And in retirement, he continued to grow his hair long and sport a bohemian goatee.

It’s funny. The popular imagination has a way of compacting eras down to a single entity. That’s why I am writing this column, you know.

Three hundred years from now, I’m sure, the rock ‘n’ roll era will be compressed into just The Beatles and their lead singer Mick Jagger. And they’ll get all the props for their hit songs Hotel California and Stairway to Heaven.

My fear is that the Beat science of the Cold War era may go down as little more than the work of Richard Feynman, a truly great man whose accomplishments seem to already be expanding to include those of his circle of friends. (Though it would be nice if someone remembered Feynman for his art, too.)

Now Feynman would’ve been first to remind us, extraordinary things tend to come from extraordinary groups of people, people who work together.

Now Feynman would’ve been first to remind us, extraordinary things tend to come from extraordinary groups of people, people who work together.

Richard Davies, by any measure, was extraordinary.

Davies died at the age of 95 on May 25, 2017 at his home in Altadena, CA.

As the Beats would say, so long, Daddy-O. You were the beatest.

Translation: He was awesome.

For aNewDomain, I’m Tom Ewing.

p.s. First, here’s Richard Feynman delivering his O ring determination after the NASA Challenger disaster.

This NASA article features Davies, Henry Richter and other 1960s Beat scientists who attended the space agency’s reunion celebration. Check it out in full, below.

NASA : Return of the Scientists as uploaded by aNewDomain’s Gina Smith on Scribd

Credits: Feynman with bongo: BigBlogTheory, All Rights Reserved; Zorthian parties at the ranch, KCET.org, All Rights Reserved. Mariner team image, NASA.JPL.gov; Public Domain.