aNewDomain — While giving a talk at Claremont McKenna College about the changing economics of professional satire in the digital age I digressed into a topic I’ve thought about a lot but, for reasons unknown, haven’t expressed much in public:

aNewDomain — While giving a talk at Claremont McKenna College about the changing economics of professional satire in the digital age I digressed into a topic I’ve thought about a lot but, for reasons unknown, haven’t expressed much in public:

And that is: Meritocracy is immoral.

The first time you heard meritocracy defined, you probably thought it was fair. I sure did. If you work hard, you deserve the rewards. Meritocracy made sense to me — because I could win by those rules.

Meritocratic Income

What’s more, under our capitalist system, working hard supposedly entitles you to a higher income. (I don’t know how to square that with the respective salaries of a coal miner and a CEO, who sits at a desk shuffling papers, but whatever.)

What’s more, under our capitalist system, working hard supposedly entitles you to a higher income. (I don’t know how to square that with the respective salaries of a coal miner and a CEO, who sits at a desk shuffling papers, but whatever.)

Under this doctrine, if you’d rather pass your time smoking pot and playing video games than working late, you shouldn’t expect to earn as much as the busy bee. If you’ve ever had to pick up the slack for someone who wasn’t pulling their weight, it’s temping to buy the argument that hard workers deserve higher remuneration than slackers.

Meritocracy has another component as well: the belief that smart people should be paid more than those who are stupid. Though ethically problematic — your IQ is in large part determined by heredity, over which you have no control — few people have a problem with this. I suspect that this is because cleverness, as opposed to raw intelligence, can be honed by studying hard in school. For Americans, whose culture is steeped in the Protestant work ethic, smarts are a corollary benefit of hard work.

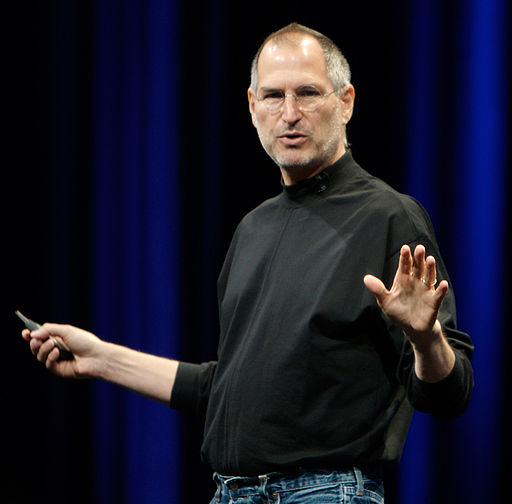

Steve Jobs, the subject of a new movie, embodies the American buy-in of meritocracy. The Apple founder was, by all accounts, a smart guy who worked hard. This assures his exalted status: design genius, business maverick, marketing king.

Steve Jobs, the subject of a new movie, embodies the American buy-in of meritocracy. The Apple founder was, by all accounts, a smart guy who worked hard. This assures his exalted status: design genius, business maverick, marketing king.

In a society with different values, however, Jobs would be remembered differently — or maybe not at all. In a kindess-ocracy, in which gentleness was prized above all else, Jobs — by all accounts a colossal jerk with a ferocious temper who abandoned his daugther at a young age — would have been homeless and destitute.

In a humility-ocracy — a society in which not taking more than your fair share was a mark of what kind of person you were — Apple’s enormous price gouges and stockpiling of humongous cash reserves would reflect Jobs’ greed and contempt for his customers. No admiring biopic for him!

Meritocracy feels hardwired, a value system so universally accepted as to be inherent. So we never question it.

When you stop long enough to question its ideological underpinnings, however, it makes little sense.

Who is to say, for example, that lazy people are worse — and ought to earn less — than nose-to-the-grindstone types? Yes, laziness is their choice. But hard workers choose too. I work hard because I enjoy it. Even if I didn’t need money, I’d work. No one begrudged Steve Jobs’ millions because he worked hard. But so what? Why should Jobs, or me, or anyone who else who likes to work hard get paid more?

Paying people who like to work hard more than people who like to do nothing is as unfair as giving better jobs to people who prefer to wear blue than to those who like red.

I can easily anticipate the primary objection to my argument: people who work hard contribute more to society.

True, they probably create and build more products and deliver more services that can quantifiably measured by capitalist economics. But lazy people are not worthless. Because they don’t spend as much time and energy working, people who don’t prioritize work have more available bandwidth to be good friends, daughters and sons, mothers and fathers. Workaholics struggle to fill those roles well, if at all.

True, they probably create and build more products and deliver more services that can quantifiably measured by capitalist economics. But lazy people are not worthless. Because they don’t spend as much time and energy working, people who don’t prioritize work have more available bandwidth to be good friends, daughters and sons, mothers and fathers. Workaholics struggle to fill those roles well, if at all.

Moreover, in a world with limited resources, it’s good for us hard workers, who are competing against one another for scarce high-end jobs and salaries and awards, not to have to contend with more rivals.

I work ridiculously hard. Yet I am perfectly fine with earning the same exact amount of money as someone who doesn’t work at all. I enjoy my life. Why shouldn’t a person whose best life involves less, or even no work, enjoy it without having to worry about starving to death?

I’m even more skeptical of the smart-people-get-more component of meritocracy than I am of the hard work thing.

Who’s to say who’s smart?

As a child I took a school IQ test that so worried my teacher that she called my mom to inform her that I was mentally disabled. Based on that result, it was a miracle that I could tie my shoes. I was so down in the double digits that, according to this test, they wouldn’t have executed me in Texas.

A few years later, however, a different IQ examination declared me a big friggin’ genius and qualified me for Mensa. Countless readers have declared my cartoons and essays the product of an idiot; others say I’m brilliant. Who’s right?

Think about all the bestselling books and blockbuster movies you’ve read and seen that sucked — after taking the word of Respected Media Gatekeepers that they were great. On the other hand, there are countless should-have-been hits that, because of timing or bad marketing, never caught on.

Where is this meritocracy anyway?

Even if we could stipulate who was smart and who was stupid, what’s so terrible about being stupid? Stupid people didn’t invent atomic fission or cluster bombs or mines that bounce three feet so they blow off your genitals. Stupid people don’t hack your email or maintain NSA computers that spy on you or use big data to get terrible politicians into high office. Stupid people don’t figure out ways to export manufacturing jobs.

It is time to admit the truth: meritocracy is BS. What we really have is a system run by people who create arbitrary measures of worthiness to perpetuate a status quo — a power structure that benefits them. Getting rid of the system and replacing it with one in which everyone’s unique gifts are valued equally — that would be meritocratic.

For aNewDomain, I’m Ted Rall.

Images in order, beginning with cover image: Man at work by CiaoHo via Flickr; Steve Jobs via Wikimedia Commons; DSing by David Goehring via Flickr