aNewDomain — Few concepts stymie me so much as does forgiveness.

aNewDomain — Few concepts stymie me so much as does forgiveness.

When I travel to China, I try to pick up a few key words and phrases. The endeavor is mostly hopeless, because my friends are from many places in China – they claim to all speak the same language but sometimes their dialects are mutually unintelligible.

So I learn how to ask for a cup of coffee from my friend from Beijing, and my friend from Chengdu says that’s all wrong, and friend from Nanjing teaches me a third way to say it.

This is the problem with forgiveness, fundamentally: it means too many thing to too many people. Ask a classroom-sized group of people and you’ll get 30 mutually unintelligible answers.

But maybe Dr. King and Malcolm X can help us shed some light on the problem.

For starters, let’s dispense with the forgetting part. If we forget the slights done to us, there is nothing to forgive. The concept loses any tenuous meaning it might have had. No judgement is rendered by the amnesiac.

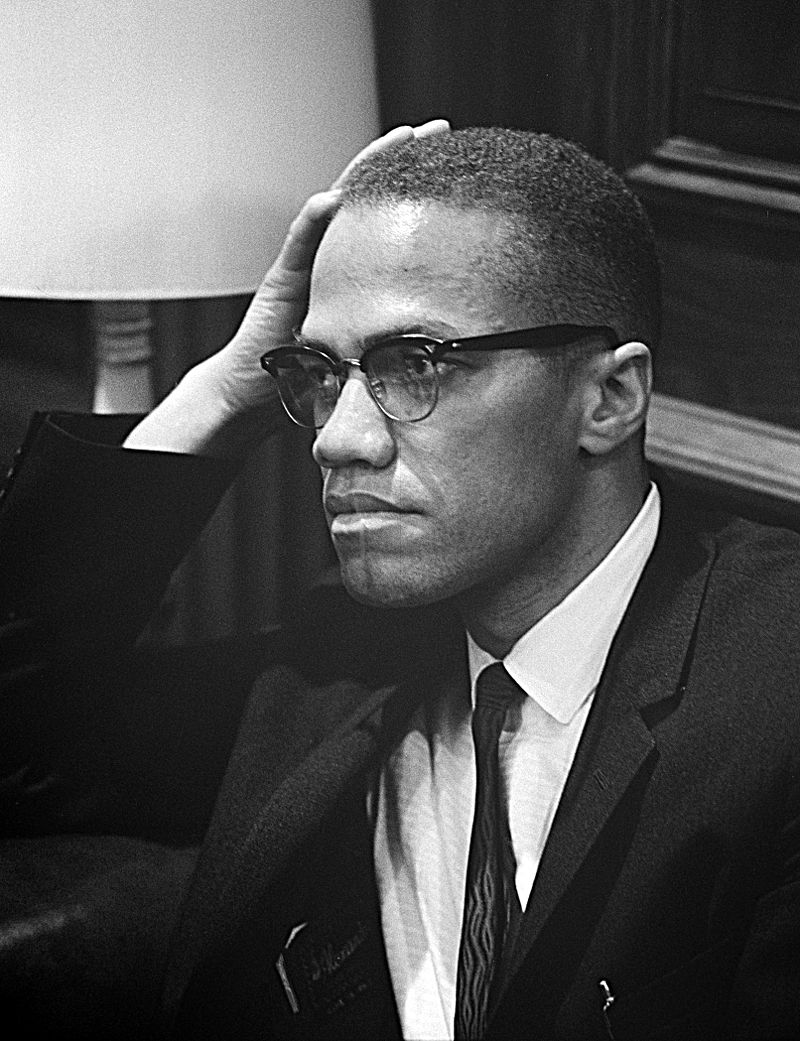

Malcolm was a very unpopular man in his time. He was beloved by many and hated by many more. His death was ultimately by violence, as he predicted. And his crime was, mostly, to remind people of the hurts done by their people. White people, who for years X referred to as “devils,” were in fact responsible for a host of crimes against blacks. We continue to be at least complicit in an economic and social system that values people according to their skin color.

Malcolm was a very unpopular man in his time. He was beloved by many and hated by many more. His death was ultimately by violence, as he predicted. And his crime was, mostly, to remind people of the hurts done by their people. White people, who for years X referred to as “devils,” were in fact responsible for a host of crimes against blacks. We continue to be at least complicit in an economic and social system that values people according to their skin color.

The Nation of Islam version of faith to which X ascribed for many years reads as something of a delusional system. X converted in prison and was a devout follower of the faith and of Elijah Muhammad. They shared an apparent folie à deux, a religious delirium that featured blacks as the ancestor race and whites as a devil race created by selective breeding to torment them for 6,000 years.

The thing with most delusions is they often have truths at their roots. Not always, to be sure, but often enough we can look at what’s under a delusion and find something too big to talk about openly. Even a psychotic person is, ultimately, pretty reasonable, reliable in their own way.

And the psychoses here are really no wilder than any other religion. While even Malcolm X described the Nation of Islam of Elijah Muhammad as a cult, scientology contains many stranger assertions (such as that the universe is a hundred trillion years old and we know the name of the being who created it). So does Mormonism (blessed undergarments can protect you), Judaism (there will be a literal resurrection at the end of the world and so you need to keep your Earthly remains in good shape against the day) and even Christianity (wine literally transmutes into blood if consumed under the correct circumstances, and you should definitely drink it).

Each of the things a religion espouses, while not literally true, reveals something of the anxieties, of the realities of its practitioner. And Elijah Muhammad’s madness was, in many ways, all too sane.

For example, whites did in fact descend from blacks.

And as X asks repeatedly of black people through his autobiography, do you actually know of any white people who haven’t done you harm?

On a geopolitical level, we have wars over religion and resources that have left Africa in shreds, India divided and China isolated. We have a stone-age Middle East in many places where mineral extraction ought to have enriched everyone. And we have, as X put it, the white man enjoying his paradise here on Earth while everyone else has to wait for Heaven in the hereafter.

All of that is context for this: He also asks why white men would expect black men to love them.

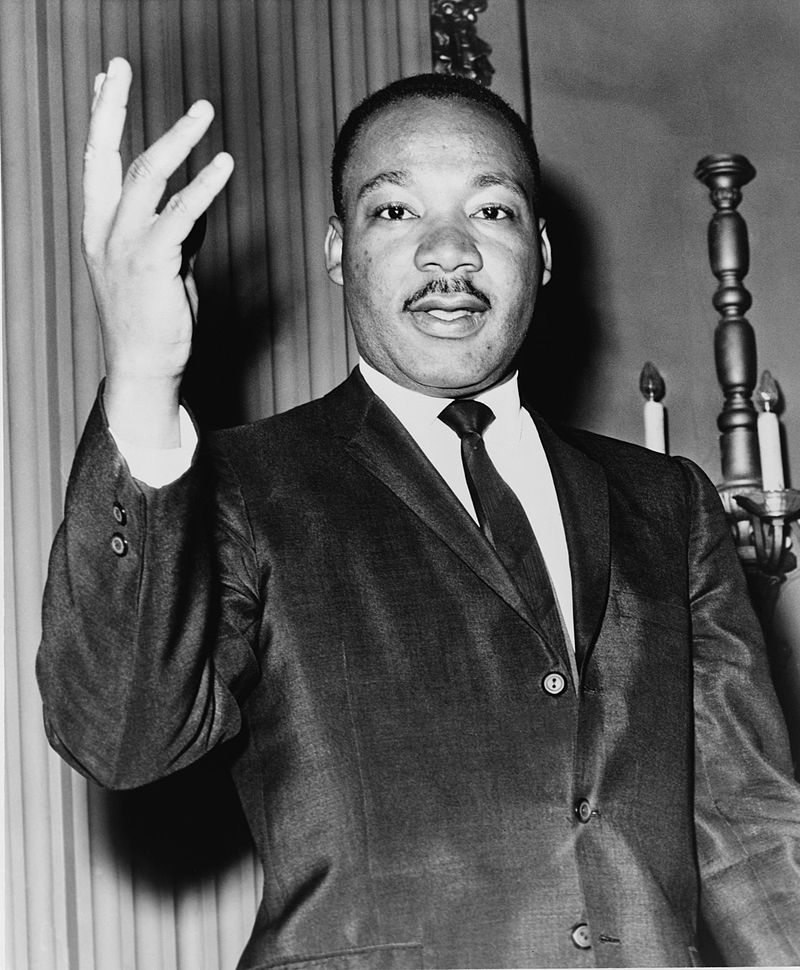

This, I think, refers to the universal love that Martin Luther King, Jr. espoused.

King spoke and wrote of agape, of the brotherhood of all men. He was a Christian, something that X could never condone or comprehend, and King espoused peaceful methods. Turn the other cheek, be patient, suffer well. The primary tactic of King’s protests was to show whites that he and his followers could bear more suffering than the oppressor could stand to heap on him.

Now King wrote more than once of his frustrations with people. With black Christian ministers who showed just the qualities X publicly abhorred, but also with the white men who arrested, fined, jailed and beat him and his. In all his years of work, though, King never raised a hand to anyone, and tried his best never to speak or write in bitterness.

So what is this love he speaks of?

So what is this love he speaks of?

X imagined love was a feeling, I think. And therefore he imagined that forgiveness was a feeling, too. I don’t think King loved white people in terms of having feelings of any particular affection for us but it is clear he loved us through his actions. In other words, the verb form of love, which is the action of putting the needs of another over one’s own. This is Christianity outside of the worship hall, the kind of faith that doesn’t complain about people saying “holiday” instead of “Christmas,” but that enacts the Christic revelation.

X wanted to hold us accountable, literally accountable. To establish a separate black nation, away from the whites who didn’t want them, so that we could relate as equals. Now X was also a scholar, a real one: he was a person capable of changing his mind based on new evidence. He did so frequently, which bemused and frustrated his followers — and detractors — at times. Later in his life, near the end, he got over black supremacy and Elijah Muhammad, enjoyed the generosity of Arab Muslims and world Islam, and made peace with Dr. King and the peaceful movement.

But he did not understand forgiveness yet.

He knew someone would shoot him. He knew it would probably be a Black Muslim, one of Muhammad’s men. It turned out to be three of them. And he faced his end bravely, right on the edge of compassion. And all the time he advocated self-defense, any means necessary.

He wanted a handgun. It’s unclear whether he filed for a permit or not. He says he did, the police say he did not. He says he wanted police protection. The police say he turned down many such offers, his people say he begged for protection and was ignored. But if anything is clear here, it is that he did not intend to mount the cross like Jesus.

King walked into violence with open hands and a resolute peace on his mind. That is love, and that is forgiveness. He forgave, forbore in advance, any violence people might do. He knew that his body might need to be sacrificed to the great work, to the learning we had to do. We had to hurt people, see that we had hurt them, and publicly feel the guilt and shame of those actions. Nothing else was going to cause any change.

His tactics were at least nominally effective. Desegregation as a matter of law is still awaiting desegregation as a matter of fact, and the voter rights provisions King saw enacted in his time are currently under assault in places like Alabama, where they are closing DMV offices in black neighborhoods to make it more difficult for blacks to obtain the necessary IDs to vote. But much of the racial violence is over with and ended in a way he could be happy about: without the resentments and recurrences created by violent revolution.

Malcolm X only spoke once in the presence of King. He is reported (by Alex Haley based on witness testimony, in X’s biography) to have told Coretta Scott King that he wanted to help: that he was presenting an alternative to King for white people to consider. They could accede to peaceful protest or suffer violent retribution. He wanted King to succeed his way, in other words, and no longer sincerely believed in violence as a solution.

His autobiography is blisteringly honest. He doesn’t portray himself in a good light, but as a product of his environment. Mean, sometimes, predatory when necessary. A dope dealer, a drug user, a thief. And he knows who made the environment, who made the man, who made the prison where he ironically found peace and scholarship. His big regret through the whole story is a young woman he turned away, a blonde woman who asked, “What can I do?” He replied, “Nothing,” and let her run, tearfully, out of his life.

His autobiography is blisteringly honest. He doesn’t portray himself in a good light, but as a product of his environment. Mean, sometimes, predatory when necessary. A dope dealer, a drug user, a thief. And he knows who made the environment, who made the man, who made the prison where he ironically found peace and scholarship. His big regret through the whole story is a young woman he turned away, a blonde woman who asked, “What can I do?” He replied, “Nothing,” and let her run, tearfully, out of his life.

Through all this, then, I think we can distill the essence of forgiveness. It is not at all a feeling or an amnesia. Nor is it a failure to hold the offender accountable for their actions. It is, rather, a commitment to love the person regardless of their actions. And by love, here we mean the verb form of love: to keep their best interests forefront, ahead even of our own. To love them, in other words, regardless of how we feel about them.

X never seems to have forgiven Muhammad, the man he credits with lifting him up when he was in prison and also with trying to destroy him, to literally kill him by the end. But he does seem to have forgiven himself, to have given himself the latitude, the permission to change his mind.

He was one of our great men, our great people. If only he had had time. His was a life defined by change, by making new decisions based on good scholarship. What might he have been next?

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

Image one: “Martin Luther King Jr NYWTS” by Dick DeMarsico, World Telegram staff photographer – This image is available from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cph.3c26559. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons; image two: “Malcolm-x” by Marion S. Trikosko – U.S. News & World Report Magazine Photograph Collection, Library of Congress, Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons; image three and cover: By New York World-Telegram and the Sun staff photographer: Wolfson, Stanley, photographer. [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons).