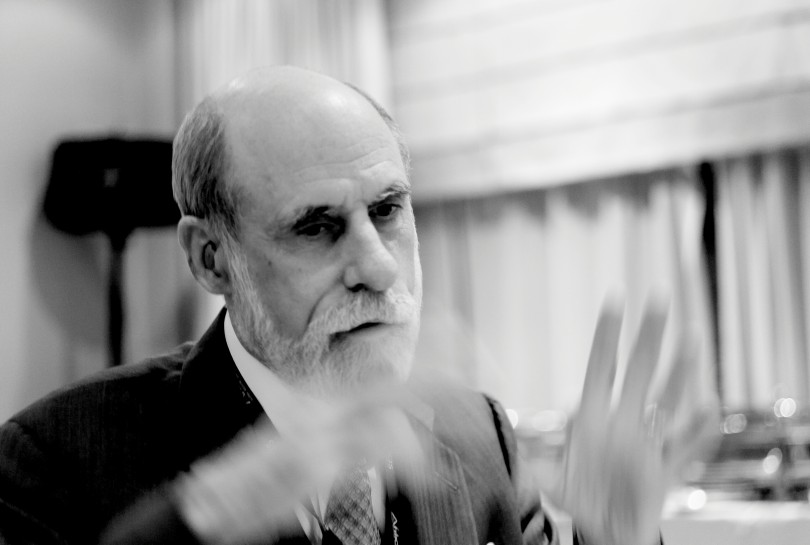

aNewDomain — In today’s Daily Dozen, I directed my 12 questions at Vint Cerf, the Internet pioneer and Google exec who is often called “The father of the Internet.”

Cerf, a vice president at Google and its chief Internet evangelist for 10 years now, is one of those rare industry figures who has secured a place in the history books. Along with former Stanford scientist Robert Kahn, Cerf designed the TCP/IP Internet network protocol, the technology on which the Internet is built and the one that made possible its earliest incarnation, known as ARPANET, back in the 1970s. Their 1973/1974 paper, “A Protocol for Packet Network Interconnection” is in many respects its cornerstone.

But Cerf, Kahn and other early 1970s connectivity pioneers could not possibly have envisioned the wholesale societal transformation that has come to pass as a result of such Internet communications protocols. Or could they?

I wanted to know what it’s like for Cerf to survey the Internet in light of what came before. It’s been awhile since we talked, and I was pleased and relieved to see he was pretty much the same as I’d left him — still as outspoken, opinionated and candid as ever. Here’s what he had to say:

Q. What surprises you?

Cerf: The influx of content on the web. The fact that millions of people want to share what they know is surprising; the advent of things like Wikipedia was surprising to me. I had not expected to see this level of interest in sharing knowledge. I’ve been pleasantly surprised.

Q. What addicts you?

Cerf: I’m not a game player, so that doesn’t addict me. But I can get lost in crawling around on Wikipedia and looking things up, lost in the sheer wealth of all the information, and clicking on links to go deeper and deeper.

And then there’s the damn email. It’s just pouring in. I feel an obligation to read it, and it is consuming.

Q. What thrills you?

Cerf: So much. The possibilities of remote medicine, remote diagnosis and remote teaching are thrilling. Also, the ability to stay in touch with a huge collection of people. I have 16,000 people in my Rolodex — the fact that I can keep in touch with many of these people is amazing. So is video conferencing, which wasn’t really ready even a decade ago. And the casual availability of the Internet. When you can just sit outside in your gazebo and reach anything — and anybody.

Q. What scares you?

Cerf: I’m not scared, but I am worried that the infrastructure upon which we are dependent is so brittle. I’m worried about malware, penetration of operating systems, insulation of trojan horses. We have a lot of software out there — software with bugs, bugs that will be exploited.

Also, as we all rely on the cloud, and software and hardware continues to change so quickly, I worry that all the data we are creating is going to disappear. The Digital Dark Age is something I’ve been talking a lot about for this reason.

And I’m worried about privacy. As we increasingly rely on (the Internet infrastructure) to control the physical things at work and at home, there are real concerns. For instance, if you had a technology that could determine if anyone was at home, a burglar could watch that data and figure out what the pattern is. Then again, in the case of a fire, you would want authorities to be able to determine who most likely is in what room. How do we grant only ephemeral access to these things without violating privacy and allowing others to? That is what we have to figure out.

Q. What gives you hope?

Cerf: I have the optimistic feeling that most people don’t mean any harm; they mean well. I’m fully aware there are some people who don’t have our best interests at heart, they want our information or money, and that is all disappointing. But somehow we are surviving in spite of it all. That gives me a lot of hope.

Q. What annoys you?

Cerf: Spam is one annoying thing. We have really great spam filters at Google, but still some gets through. And the incredible trivial nature of so much stuff online is annoying, too. There are 400 hours of video being updated every minute on YouTube, for instance.

Q. What pisses you off?

Cerf: People who blame the Internet for things they should be blaming themselves for. It’s like looking in the mirror and blaming the mirror for how you look. I’m annoyed when people don’t realize that the index is anything but a reflection of society when they blame Google for what is on the Internet. You know, Google just indexes the web. We don’t create its content. People forget that.

Q. What keeps you awake at night?

Cerf: Mostly my concern that we need to increase the security of our infrastructure.

Q. What blows your mind?

Cerf: I didn’t dream all this would happen back in the early days (of Arpanet). But I did believe society would open up society in ways I couldn’t imagine before. It has. I am satisfied that this has happened.

Q. What do you regret?

Cerf: The fact that the net is abused is something I regret. Then again, there is far more utility than harm in it. We need to make sure we are always emphasizing freedom, and that we continue to do so.

Q. As “father of the Internet,” what advice do you have for its children?

Cerf: We need to teach today’s children critical thinking. The Internet confronts them with all kinds of potential sources of misinformation and inaccuracies. In school, we should say to them, “Look at these 12 sites and evaluate them. Tell me if each site is accurate or not. And, by the way, you haven’t done the assignment if you are just using online sources and not (primary) sources. There are things in the library you are not going to find online.”

This sort of training gives the child the beginnings of the type of critical thought they’ll need, so they don’t just accept everything and everyone they see at face value. Unfortunately, there are people who believe we should not teach children to question what they’re told, not to question authority. This is a mistake. As the saying goes, everyone has a right to their opinion, but not to their own facts. We need to teach them that.

Also, we should teach programming in schools. Not because children need to be programmers, but because they should learn the discipline so they can understand how to break things into logical pieces. It’s a way of thinking that’s powerful — and it applies to many, many other things.

Q. If you were a DOS application, which application would you be?

Cerf: Oh, that’s a funny question!

Well, let’s see. I know I wouldn’t want to be a Microsoft application …

What I would want to be is an application that connects people to other people. Because I spend most of my time doing that. That is what I truly love to do.

For aNewDomain, I’m Gina Smith.

The 1973 paper Vint Cerf and Robert Kahn published in 1974, called “A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication,” is readable in full below.

A Protocol for Packet Network Intercommunication: Cerf, V.G. & Kahn, R.E., 1974

Cover image of Vint Cerf: By Joi Ito from Inbamura, Japan (Vint Cerf) [CC BY 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, All Rights Reserved