aNewDomain — Death and children. It’s a pairing that turns you off right away. It’s risky. Visceral. We want to protect our children from harm, sure, but also even from any thought of harm, from the very idea of it. Keep them from witnessing violence of any kind.

— Death and children. It’s a pairing that turns you off right away. It’s risky. Visceral. We want to protect our children from harm, sure, but also even from any thought of harm, from the very idea of it. Keep them from witnessing violence of any kind.

Mostly.

I mean, my wife teaches fourth grade, and she brings regular reports that kids in her school watch “The Walking Dead.” And that’s clearly … something.

But for the most part, we don’t want our children to think of death. They outlive their pets, and we contrive ways to keep the death of their friends away from them. We for sure turn off the nightly news – I’d rather my son see TWD than that. We sanitize.

But for the most part, we don’t want our children to think of death. They outlive their pets, and we contrive ways to keep the death of their friends away from them. We for sure turn off the nightly news – I’d rather my son see TWD than that. We sanitize.

Is that all for the best?

The denial of death is a luxury available only to very wealthy societies. We have a whole underclass devoted to keeping death a secret, sanitizing it, sterilizing it. Coroners and morticians, undertakers. Preparers of bodies.

It wasn’t always like this, you know. Bodies used to stay in your home a few days after the person had passed. The smell of death was masked with flowers, and hence the tradition of flowers for sympathy. Your loved one would lay on the dining table or in your bed, awaiting the day of the funeral. The family washed and dressed the body. It was unavoidable.

This is what I mean by sanitized. We aren’t castrating hogs on our farm, putting down the runts, chopping the heads off chickens and plucking them for supper. Death is not a daily event but something we have to do with our children, a conversation that must be had. Like The Talk.

Are we having it? Are you ready for that talk?

Are we having it? Are you ready for that talk?

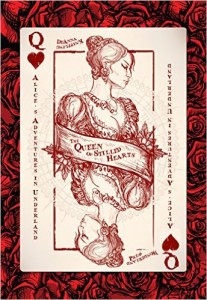

Enter DeAnna Knippling. Her new book, Alice’s Adventures in Underland: The Queen of Stilled Hearts, is a fascinating bit of line-blurring fiction. It stands out, difficult to put into a normal genre. It’s horror, but it’s also fantasy, historical fiction, literary fiction …

It is the story of the story of Alice. How did Lewis Carroll, aka Charles Dodgson, come to write the iconic story? What was his relationship with Alice, then just a young girl?

The story flip-flops back and forth between the events around the creation of the story and the tale itself.

And just to keep things crazy, there’s a twist: Dodgson is a zombie, kept as a pet, a kind of servant.

Some of the themes of Alice are amplified here, the covers ripped off. Dodgson calls his stories a bit of nonsense. An amusing pass-time. In fact, though, we’re wondering what it means to be sane in a crazy world, and to court madness.

Ultimately, what is madness if not death?

You’ve lost yourself. And a self that has gone on has died.

When we fear madness, we fear the loss of identity, walking death. And Underland, the place Dodgson says zombies come from, is full of walking death.

Alice has to learn to pass as one of the dead, pass among them, navigate the peculiar madness. The madness of the dead mirrors, as it must, the madness of the living. This is Sartrean banality, an echo of Shakespeare’s famous lines:

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

(MacBeth)

Life is banal and full of banality. “A bit of nonsense” is all we get. We strive for meaning and here is Dodgson’s desire to be a minister, as the real Charles Dodgson was, but zombies cannot be ministers. Once you have seen death then no banal explanations suffice any longer.

There’s more here. Like any ambiguous stimulus, you can stare into Alice and see whatever you want. It’s the current of unease through the story, never fully realized and never fully resolved, that brings me back.

That’s the unease that fills us when we try to tell our children what death means, the unease that makes us want to gloss the whole thing over with stories about Heaven, eternal life, loved ones looking down on all our earthly actions.

Just a bit of nonsense to pass the time.

Just a bit of nonsense to pass the time.

In our world, in our country, children are protected from death and the idea of death. We think we have all the time in the world, that medicine can save us. In Alice and, indeed, in Victorian England, there were no such protections.

Life and death were brutal and constant and unavoidable. And we had constant war, slavery, sex crimes, transportation, piles of hands cut off native workers who did not bring us enough booty.

It isn’t enough to gloss over death with pretty stories, or to expose us constantly to it, or to ignore it.

So are you ready yet for that talk?

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

Image one: Amazon.com, All Rights Reserved; image two: TheTimes.co.uk, All Rights Reserved; image three: SiliconAngle.com, All Rights Reserved; image four: SiliconAngle.com, All Rights Reserved; image five: DeadBuriedandBack.com, All Rights Reserved.