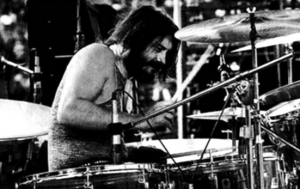

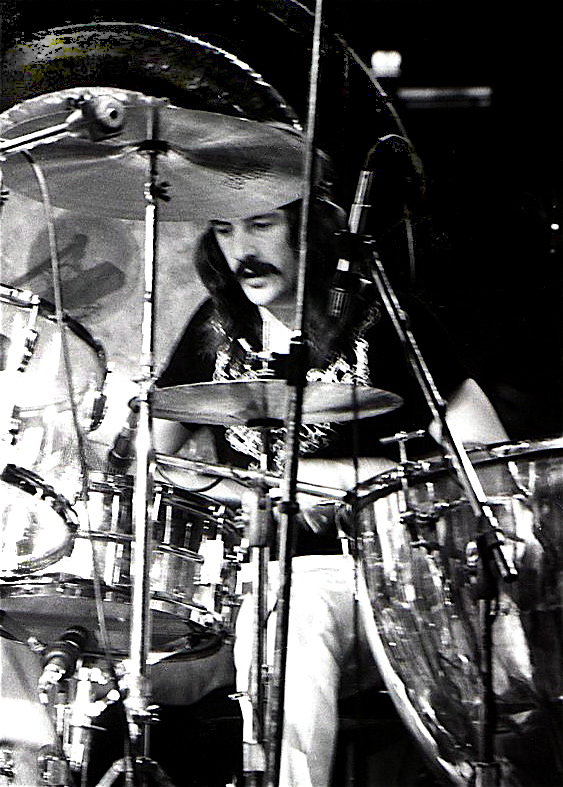

aNewDomain — If you love rock as much as I do, you’ve got to honor the late Led Zeppelin drummer John Bonham. Now would be a great time to do it. It’s the 35th anniversary of the famed drummer’s passing. One of the most influential and revered drummers in rock music history, Bonham died Sept. 25, 1980, of a pulmonary edema resulting from a vodka binge. He was 32 years old.

aNewDomain — If you love rock as much as I do, you’ve got to honor the late Led Zeppelin drummer John Bonham. Now would be a great time to do it. It’s the 35th anniversary of the famed drummer’s passing. One of the most influential and revered drummers in rock music history, Bonham died Sept. 25, 1980, of a pulmonary edema resulting from a vodka binge. He was 32 years old.

Foo Fighters’ Dave Grohl summed up the effect Bonham produced during Led Zeppelin’s heyday in the late 1960s and 1970s. He said, “John played the drums like someone who didn’t know what was going to happen next — like he was teetering on the edge of a cliff. No one has come close to that since, and I don’t think anybody ever will.”

Bonham always was a larger than life personality, and a real Jekyll and Hyde persona, too, according to those who knew him best. Robert Plant remembers him as “a great, warm, big-hearted friend.” How much he missed his wife, son and daughter while on tour. “Bonzo” Bonham, as he was known, was a tight family man with a great sense of humor. But when he was in his cups, he was the Bonzo Monster, getting plastered and riding his motorcycle through hotel hallways while on tour. Press notes given to journalists covering the band on tour in the mid and later 1970s would read something like, “Never speak to a band member unless they speak to you first. And never make direct eye contact with John Bonham. This is for your own protection.”

But all this is a sidenote to his masterful, incredible drumming.

But all this is a sidenote to his masterful, incredible drumming.

The hardest-hitting drummer of his day, rivaled in that regard (perhaps) only by Cozy Powell later in the 1970s, Bonham was, first and foremost, loud as hell. Louder, maybe.

Long before guitarist Jimmy Page and future Led Zeppelin manager Peter Grant convinced him to join the group in 1968, Bonham was getting kicked out of bands — for playing too loudly, according to his official biographers. He would use the largest drum sticks he could find, and call them his “trees.”

Always in search of the ability to play louder, in 1973 Bonham began playing, for concerts, a Ludwig Vistalite kit. These drums could provide increased volume and power, as was engendered by the set’s denser, non-porous shell.

Scroll below the fold to see some of the best YouTube videos I could find capturing Bonham.

R&B meets jazz meets metal: the Bonham equation

Despite his heavy hitting ways, Bonham had an R&B and jazz-influenced style of playing which he utilized to dramatic effect.

He could play with precision just behind or just in front of the beat, and he made incredibly creative use of triplets and sixtuplets, although he never was a “swing” drummer. These techniques coupled with his pure volume enabled much of the edge-of-mayhem song arrangements for which Led Zeppelin became loved, famous and immensely wealthy.

But as time, tours and increased fame wore on, Bonham’s already prodigious appetite for alcohol grew. This spelled doom.

It was only a matter time, those who knew him best worried, before Bonzo would go gonzo.

And so he did.

The day the drummer died

The day the drummer died

The problem that would kill him first became evident for John Bonham a few months before the day of his death.

On June 27th, 1980 at a concert in Nuremburg, Bonham began playing insensibly, falling behind the beat (way behind) after just a couple of songs, and then eventually passed out entirely behind his drum kit, causing the show to be canceled. It would never be rescheduled.

The official press release from the band stated that Bonham had stomach problems because he had eaten too many bananas earlier that day (ha!). More likely, he’d drunk too many banana cows (just my informed speculation).

On the day of September 24th, while preparing for the North American leg of Led Zeppelin’s 1980 tour, Bonham downed the equivalent of 40 shots of vodka, as an official coroner’s autopsy later confirmed.

Led Zeppelin assistant Rex King, who picked up Bonham that morning to go attend rehearsals at Bray Studios, reported that the drummer had nothing to eat except two bites of a ham roll when they stopped for breakfast. There, Bonham also downed four quadruple vodkas, King said. The band and crew members report that Bonham ate nothing else all day as he rehearsed and downed shots.

Eventually, the drummer passed out. He would then be taken to a bedroom at Jimmy Page’s house, which wasn’t far from Bray Studios, in Clewer, Windsor, UK, a home fans know as “The Old Mill House.”

Rumors would persist later that Bonham died in another one of the houses which Page owned at the time — the former mansion of infamous black magic practitioner Aleister Crowley, whom Page openly admired and studied.

But that’s not where Bonham bit it.

According to authorities, Bonham had passed out sometime after midnight and was placed in bed, on his side. Sometime during the night, Bonham’s body began to eject the copious amounts of alcohol that it couldn’t process, but the drummer was so knocked out from vodka that his body wouldn’t let him wake up.

Tragically, Bonham died in the wee hours of the morning from pulmonary edema. In other words, after throwing up in his sleep the liquid waste from his guts eventually settled into his lungs, drowning him.

It was a horrific way to die. Led Zeppelin bass player and keyboardist John Paul Jones found Bonham dead on the morning of September 25, 1980.

Some suspected foul play at first, because the inebriated Bonham had been placed on his side, the wrong way always, to put down a drunk. But Bonham and all of the Led Zeppelin band members and crew members were experienced drinkers, and any one of them would know how to place someone they believed had merely fallen asleep after “normal” amounts of drinking, authorities concluded.

Besides, there was no motive. The police quickly decided that there was no foul play or malicious intention.

Two months later, Led Zeppelin announced that the band was permanently finished, uninterested in carrying on without the irrepressible, irreplaceable Bonham.

There would never be a 1980 North American Tour for Led Zeppelin for its latest album, and its last, “In Through the Out Door” (ITTOD).

There would never be a 1980 North American Tour for Led Zeppelin for its latest album, and its last, “In Through the Out Door” (ITTOD).

There would never be another tour, ever again, anywhere.

So going backwards, the band unknowingly ended its final tour on July 7th, 1980 at Eissporthalle in Berlin, Germany. And, unknowingly, it had given its farewell tour to North America in 1977 — a tour that was cut short after singer Robert Plant learned of the tragic death of his little son Karac from a mysterious stomach virus.

Speaking to “Rolling Stone” magazine in 2014, Page was asked why the band didn’t go on after John Bonham’s death. Page replied:

Led Zeppelin wasn’t a corporate entity. Led Zeppelin was an affair of the heart. Each of the members was important to the sum total of what we were. I like to think that if it had been me that wasn’t there, the others would have made the same decision. And what were we going to do? Create a role for somebody, say, ‘You have to do this, this way?’ That wouldn’t be honest.”

Out Through the In Door? It would’ve been better …

The 1980 Led Zeppelin tour was in support of their August, 1979 studio release, “In Through the Out Door” (ITTOD), recorded in late 1978. This would prove to be the band’s and John Bonham’s final studio album.

From the outset, the album was fraught with controversy. After the death of his five-year-old son, Robert Plant decided he wanted nothing more to do with Page and his black magic ways, even though the band never broke up and, of course, black magic could never officially be verified as contributing to the little boy’s death.

From the outset, the album was fraught with controversy. After the death of his five-year-old son, Robert Plant decided he wanted nothing more to do with Page and his black magic ways, even though the band never broke up and, of course, black magic could never officially be verified as contributing to the little boy’s death.

Plant got infuriated a year later when reading in some magazine that Page had enlisted Roy Harper to write lyrics for a new Led Zeppelin album. He broke his silence with Page and a new album got written, according to Stephen Davis in his book, Hammer of the Gods: The Led Zeppelin Saga.

Page wasn’t happy with the final album, and he would make that fact clear, at least indirectly, in some later interviews. He dismissed the record (ITTOD) as being essentially a Robert Plant solo effort and “a little soft.”

It’s true that the album’s writing and arrangements were dominated by Plant and John Paul Jones, with the latter’s newly discovered modern synthesizers all over the record, marking the first (and last) time that Jones dominated a Led Zeppelin album’s songwriting. The album features the only two original Led Zeppelin compositions on which Page is given no songwriting credits (“All My Love” and “South Bound Saurez”), while Bonham isn’t given any songwriting credits at all.

Jimmy Page did still engineer and produce “In Through the Out Door,” as he had produced every Zep studio record.

Jimmy Page did still engineer and produce “In Through the Out Door,” as he had produced every Zep studio record.

There’s a claim that Page deliberately mixed Plant’s vocals low, and a listen to the album’s tracks seems to confirm this.

The reasons for the change in dominance in the band were simple, though. At the time of the recordings, Bonham was fighting what had become full-blown alcoholism and Page was a heroin addict. Both men would all too often miss scheduled recording sessions, according to Jones and Plant. Overall, Page’s playing on the record is clearly not up to his usual, previous standards.

Led Zeppelin also had to release the album in a rock ‘n’ roll cultural climate change.

In England, by 1980, punk rock had come to dominate, especially in the eyes and ears of the media. Hard rock bands with eight-minute or 10-minute songs and mythopoetic lyric themes like the ones Led Zeppelin had perfected were, if not dinosaurs, apparently on the way out. Even so, in the U.S., where punk was slower to take hold, the appetite for Led Zeppelin’s signature themes and sound still was huge. People hungered for more.

But there was something to be said for Page’s dislike of or disappointment with ITTOD. The song selection on the album is inconsistent, at best, according to a lot of listeners, and I’m one of them.

Some of the album’s material comes across merely as comical or even a parody of the band, such as the ridiculous rockabilly inspired “Hot Dog” and the Caribbean-inspired break in the midsection of “Fool In the Rain,” which became one of the record’s three radio hits. It was a break I was not alone in finding annoying. And then there was “All My Love,” written for Plant’s dead young son, Karac. Still, it became a big FM hit in the U.S., despite the desperate sound of Led Zeppelin straining to do pop rock.

Page had already discussed with Bonham how the next Led Zeppelin album was going to have to go back to the earlier, more urgent, heavier sounds.

But because of Bonham’s vodka-fueled passing, no such album would ever be made. In a world where tragedy begets tragedy, that was the death that John Bonham’s death hastened.

Today, I mourn both those deaths.

Honor John Bonham by making your own, better “In Through the Out Door.” Here’s how.

I always loved half of ITTOD and hated the other half. However, when I bought the record I also bought Coda along with it. Coda was a 1982 album of studio cuts that never made it onto the albums they were recorded for, plus one “live” soundcheck recording from 1970 (a cover of Willie Dixon’s “I Can’t Quit You, Baby”).

When I learned that three of the tracks on Coda were written and recorded for ITTOD, I realized I had something like the real album as the musicians must have originally imagined it.

Through the years, I’ve listened to “my” ITTOD album with great satisfaction, and I invite you to try it out for yourself. Burn a  CD or put together a playlist that goes like this …

CD or put together a playlist that goes like this …

1) “In the Evening” (keeper). The original opening song on ITTOD is one of the greatest Led Zeppelin songs, period. It opens with some electronic music out of some horror film which, in fact, Page had composed for the Kenneth Anger film “Lucifer Rising” (1972) before, cued by Robert Plant’s vocal, the band kicks in with classic Zeppelinesque ferocity and bombast, even with Jones’ synthesizers and a relatively thin Telecaster-sounding Page guitar in the mix. Between the intro and Page’s punched-in, demented guitar solo, together with Plant’s classic blues lyrics (appropriately wailed, moaned and shouted), the song makes the perfect pre-hyperlinks link-back to the band’s earlier days.

2) “Ozone Baby” (from Coda). Get rid of that silly “South Bound Saurez” nonsense and put in this Page/Plant song from Coda. There are no synths, and the song features Jones on eight-string bass (and another punched-in, demented solo by Page). The song evokes the prevailing Punk of the day without bowing to it, and in addition to Jones’ new found synthesizers may have signaled the band’s 1980s direction.

3) “Darlene” (from Coda). We don’t need fools in the rain. This bluesy hard-boogie song gave songwriting credits to all four band members and instead of Jones on synths it features him on piano and bass pedals. A perfect fit with both the new and the traditional Zep sound.

4) “Wearing and Tearing” (from Coda). This Page/Plant song could have been a thrash metal prototype and is a helluva lot more exciting than “Hot Dog”. The lyrics, however, certainly seem to point the finger at Page’s heroin addiction — the main reason I can think of why it ended up on the cutting room floor. Page would later go on to perform the song live (with Plant singing) at the 1990 Knebworth British Rock festival. At that live concert, Plant clearly sings “You know, you know” in the chorus section. But on the original song, it’s undeniable that it sounds as if he’s singing “A needle, a needle, a needle.” Perhaps he isn’t, but it begs the question: did Page, at least subliminally, mix the vocals so low and with so much echo that people could easily mistake “you know” for “a needle?”

5) “Carouselambra” (keeper). Synth-heavy but with some excellent guitar and bass playing, especially in its middle section, this is Zep’s final epic song and a fine one.

6) “Bonzo’s Montreaux” (from Coda). The rule here is that something from Coda has got to replace the sentimental syrup of “All My Love”! So you know,”Bonzo’s Montreaux” was an all-percussion instrumental recorded for the 1976 Presence sessions, and it features electronic treatments and overdubbed orchestration (from Bonham’s drums) added in by Page, thus making it a perfect fit to follow up the electronic outtro to “Carouselambra.” This Bonham/Page piece is rife with both the brought-forward-from-the-past electronic music to kick off the album and the use of lots of leftover material from the previous sessions in the making of the monumental Physical Graffiti double album (1975). It’s a fitting tribute to Bonham.

7) “I’m Gonna Crawl” (keeper). The last blues crawl Zep would ever record. Synth-heavy, but it finishes bluesy and powerful. A truly great take on the unique Zep blues tradition.

Program those seven tracks to play in seamless order, listen over and over and you be the judge: Should that collection have made the last Led Zeppelin record?

For aNewDomain, I’m Brant David.

All images courtesy of: The Led Zeppelin website, All Rights Reserved.

Except: Cover image of John Bonham: via YouTube, All Rights Reserved; image of Led Zeppelin playing in Berlin at its final concert with Bonham: UltimateClassicRock.com, All Rights Reserved; John Bonham 1975 image: “John Bonham 1975” by Dina Regine – http://www.flickr.com/photos/divadivadina/3555264805/. Licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 via Commons; John Henry Bonham gravestone: “Grave JohnBonham sept07” by Ebbskihare – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Image:Sept07.JPG. Licensed under Public Domain via Commons.