aNewDomain — Let’s not start too much with why to write women characters. I’ve already covered that in my piece about racebent Hermione. And I’m not suggesting we all watch out for the Politically Correct (PC) police, either.

If you don’t want to write strong female characters, nobody is going to try to make you. Just, consider wanting to.

I mean, what’s so horrible about including some characters from the 50.1 percent of the population who don’t call themselves men?

Women’s literature is a genre because we need it. We need it in small part because women are different from men; we need it in large part because the rest of literature is largely blind to the needs and even existence of women.

I remember a day oh, 20 some years ago. I was sitting at a conference table with some White officers and a Black sergeant and the topic of discussion was Black Entertainment Channel (BET). One of the officers wondered why we have to have BET. And what would happen if somebody launched a White Entertainment channel.

The sergeant’s answer has stuck with me.

He said, “You already have that. It’s call CBS.” He could have said ABC or NBC or really any other channel that existed at the time.

See, women’s literature is literature. But what we call literature is mostly about menfolk.

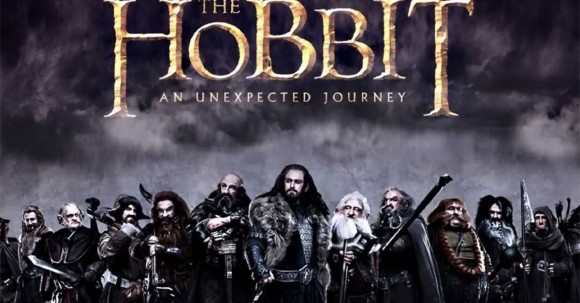

Have you actually stopped and read The Hobbit or Lord of the Rings?

Have you noticed anything weird about those stories?

How about: there’s one important female character, the Horselord’s daughter. She fights like a man. The couple of other females mentioned are there just to be beautiful and appeal to or inspire the males.

The scriptwriters had to post-hoc some more important things for the few women to do besides look hot.

That’s pretty typical.

That’s pretty typical.

I hear lots of excuses about writing female characters, but I suspect folks just never thought about it. The primary excuse: I don’t know how.

The answer to that is this: men and women are virtually identical. Men are many times more likely to rape or murder.

They’re mildly better at sports and math, on average.

In the usual course of events, men are more promiscuous and earn more money and do certain kinds of jobs with greater frequency.

But those differences are averages.

Except for the violence, there are quite small average differences between us. These differences are In size, strength, age, desire, computational skills and so on.

And, as it turns out, it’s difficult to ascribe really any of those small, average differences to the presence of a vagina vs. a penis.

Boys get called on more in math class, for example, and engage in more physical play, and are encouraged to eat everything on their plates. The adults that result from our inevitably sexist parenting are going to have socially created gender differences organized along sex lines.

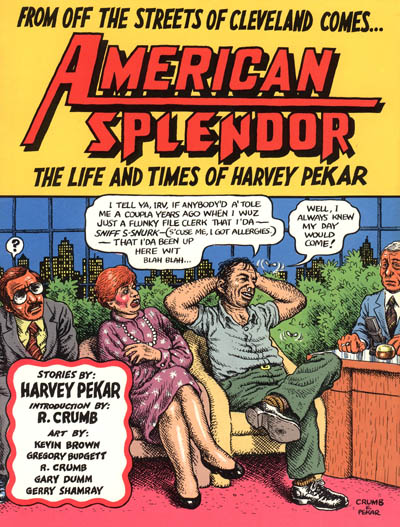

But wait a second: is your story about average people doing average things? Harvey Pekar made a living showing us the dullness, the utter banality of American life in his American Splendor illustrated stories.

But when was the last time you picked up a book and thought Hey, I hope everyone in this story is completely average?

So, look: What do women want?

Women want what men want. They want a pretty lover and someone they can depend on. They want casual sex sometimes, and faith and trust, and a place to call home.

They want a partner who won’t be a little boy they have to take care of.

Men want love with their intimacy just as much as women want that and the converse is a stereotype. And given the right conditions (people aren’t all judgy- and murder-y) women are as promiscuous as men.

It’s pretty simple, really.

Women are good at anything men are good at. No woman ever beat any man at top-level individual Olympic sports, that’s true: The strongest, fastest, high-flyingest people will always be men.

But most of us guys aren’t at all Olympic athletes. Extraordinary women can whip even better-than-average men at their own games.

Look through your science textbooks. We talk all the time about the fathers. The forefathers, the father of psychology, the father of neurobiology. Where are all the mothers? Thing is, our science disciplines were all founded at a time when women weren’t allowed to go to graduate schools.

Women make great scientists, as great as any other scientists. Their menstrual cycles don’t make them unreasonable for a week out of every month and more than male scientists are distracted by comely graduate students. We all compartmentalize and get the job done.

Is there any particular reason all four principle characters on Big Bang Theory have to be dudes? That we romanticize bro-dom?

What would we do with a show about four women friends?

Call it girl stuff and ignore it. That’s what.

BBT has worked hard to include female characters. Everyone important, though, is shagging one of the male characters.

So, here’s what you do. Write your story. Do it your way, the way you want. Then count up characters and find out you forgot to write any women other than love interests who inspire or who are the stakes, but who actually don’t do anything.

Now, take one of the men you wrote and change his name to that of a woman. Don’t make any other changes – not to her actions, not to her attitudes, not to her strengths or emotional expressions.

I bet you five dollars you just took a character who was borderline, on that edge between being boring and having potential, and made them incredibly interesting. Unless you have her peeing standing up or something, people aren’t going to read that character and think, that’s a man with a woman’s name.

To the extent that she violates their gender expectations, the reader is going to fill in the blanks where they can – and wonder why.

Wondering why is what makes character interesting.

Gender-bending is also a great idea. We can replace an iconic male character with a female. This can highlight the absence of females from sexist history. It can also, though, highlight the ridiculous premises, stories and behaviors we accept from male characters. Our opinion of men is so low that we accept sexism and gross acts of violence, sociopathic heroes. Putting a woman in the same situations could be very enlightening.

Take Jack Reacher.

Lee Child’s larger-than life ex MP, solo A-Team character kills without remorse, uses violence often as a first recourse, and thinks nothing of gross property damage. His philosophy is you fuck with me or mine, you deserve what you get. You opened a door you shouldn’t have opened.

The Reacher books are really easy reading. Compelling, even.

My own pet conspiracy theory is that Lee Child is really Stephen King in disguise, or a character actor hired to play himself. But we, as readers, too easily accept that a 6’5” man can wander the countryside getting involved in plot after plot, murdering his way clear, and experience no particular consequences.

What if we rewrote the Reacher story with a female lead?

She’s over six feet tall, made of muscles, hard-nosed as any man.

When someone gets in her way she asks them nicely to move aside and, if they give her any crap, she crushes their face with a vicious head-butt. Then she goes on about her business, more concerned that her shower took exactly seven minutes than that she might have killed or brain-injured someone: they opened a door they shouldn’t have opened.

Throws the whole thing into a different light. Because we have particular preconceptions about men and women, the sex context shows us how inappropriate these actions are, this violence and unconcern. Our opinions of men are so low, we accept Reacher without a lot of questions. Make him a her can shock us into thinking about it.

Wouldn’t that be interesting, and sell some copy?

And could it be worse than casting Tom Cruise in the film role?

Some folks disagree with the idea that we’re basically the same. They’re mostly older folks, who grew up in a time when the codes for male and female behavior were much more segregated than today.

In the modern age, men can be caring and sensitive, women can be bold and murderous.

But the last thing is this: Our culture is shaped to a large degree by our fiction.

The battle for equal rights for same-sex couples has benefitted by mainstreaming.

Television shows and movies with non-stereotyped gay characters have made it much easier to identify with the people asking for their basic civil rights. They have normalized a trait that as recently as 1978 was treated as a mental illness.

The Cosby Show did as much for race relations as anything else, portraying an American family who happened to be black. Everybody watched it and culture changed, if just incrementally.

When we write women characters really carefully to make men and women very different, we might not be making those characters more realistic. I remember a British comedian saying most comedians don’t impersonal celebrities, they impersonate their favorite impersonations of celebrities. When we write with careful attention to how men and women are different, we’re really in danger of just repeating what we’ve seen in other novels or stories or movies.

In other words, we’re in danger of stereotyping, and that makes for lousy writing. If you want a character who is unique, believable and compelling, she can’t be a stereotype.

That means this: If you don’t know how to write a female character, that’s the strongest sign you should do it. You’ll be great at it. Because if you *know* how to write women — or men, for that matter — you’re just laying down cliché after cliché.

Stop it. And start writing.

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

Credits: image one: UK Telegraph, All Rights Reserved; image two: Mashable, All Rights Reserved; image three: SideshowCollectors.com, All Rights Reserved; image four: Anokatony, All Rights Reserved; image five: The Big Bang Theory cast, via Wikipedia; image six: MovieTorrents.net, All Rights Reserved.