aNewDomain commentary — Movies are the historical record.

Americans experience the Vietnam War by watching “Apocalypse Now,” slavery in “12 Years a Slave,” and D-Day through “Saving Private Ryan.” A lot more Americans watch historical movies than read history books. Which, when done well, is not a bad thing. I’ve read countless books about the collapse of Nazi Germany, but the brilliantly-acted and directed reenactment of Hitler’s last days in his Berlin bunker depicted in the masterful 2004 German film “Downfall” can’t be beat.

When a film purports to depict a historical event, it becomes the only version of what most people believe really happened. So, as we move further into a post-literate society, misleading historical filmmaking isn’t just a waste of two and a half hours.

It’s a crime against the truth.

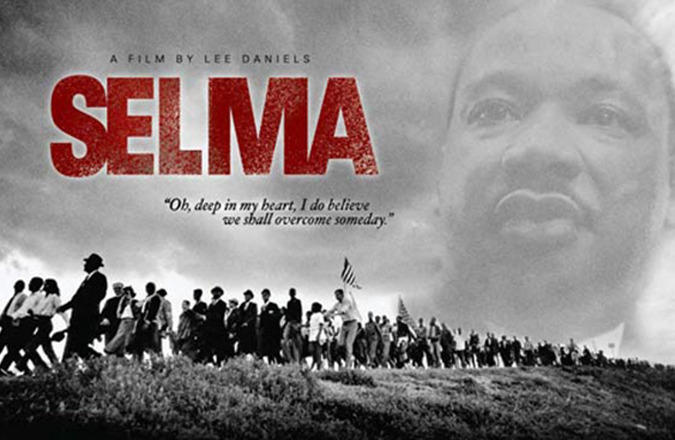

Ava DuVernay-directed film “Selma” is at the center of controversy, both due to its semi-snubbing by the Oscars – viewed as backtracking from last year’s relatively racially diverse choice of nominees – and accusations that it plays loose with history.

Former LBJ aide and Democratic Party stalwart Joe Califano fired the first shot with a Washington Post op-ed. “Selma,” wrote Califano, “falsely portrays President Lyndon B. Johnson as being at odds with Martin Luther King Jr. and even using the FBI to discredit him, as only reluctantly behind the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and as opposed to the Selma march itself.”

Former LBJ aide and Democratic Party stalwart Joe Califano fired the first shot with a Washington Post op-ed. “Selma,” wrote Califano, “falsely portrays President Lyndon B. Johnson as being at odds with Martin Luther King Jr. and even using the FBI to discredit him, as only reluctantly behind the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and as opposed to the Selma march itself.”

He’s right.

Robert Caro’s magisterial four-volume biography of Johnson portrays him as a deeply flawed man, but one whose passion to push for desegregation and an end to discrimination against blacks informed his political career throughout his life, though it wasn’t always obvious to his detractors.

It was only after JFK’s assassination brought him to power – actually, a movie portraying Kennedy as reluctant to support civil rights would have been accurate – that he had the chance to push through both the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which he did aggressively and quickly, despite what he famously predicted would be the loss of the South to the Democratic Party for a generation or more.

Johnson gave J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI too much latitude, which Hoover used to harass King, but there’s no evidence that, as the movie depicts, it was LBJ who ordered Hoover to send audiotapes of King having sex with other women to his wife. And let’s be clear: every important conversation in the Oval Office was being taped. We have the transcripts. We would know if that had happened.

Califano takes his defense of his former boss too far when he says “[the march on] Selma was LBJ’s idea.” Otherwise, the facts are on his side: the LBJ in “Selma” is not the LBJ King knew.

Fans of the film argue that it doesn’t matter.

“Did ‘Selma’ cut some corners and perhaps tilt characters to suit the needs of the story? Why yes — just like almost every other Hollywood biopic and historical film that has been made,” the media writer David Carr writes in The New York Times.

Yes, in a movie the story is the thing. It’s hard to imagine “The Queen” — about the inner workings of the British monarchy and its relationship to then-Prime Minister Tony Blair in the aftermath of the death of Princess Diana — working without a lot of made-up dialogue between the principals. However, the great detail of these obviously private conversations signals to the audience that they don’t come out of a transcript, and that we must be witnessing a fictionalized account.

There comes a point, on the other hand, where so many corners get cut and so many characters get tilted that a film ceases to resemble history and enters the territory of complete fabulism and, in the case of “Selma” and LBJ, retroactive character assassination.

The clash between MLK and LBJ – King pushing, Johnson resisting – isn’t merely some extraneous detail of the script in “Selma.” It’s the main plot of the film.

It didn’t go down like that, yet thanks to this BS film, a generation of Americans will grow up thinking that it did.

Alyssa Rosenberg of The Washington Post repeatedly calls “Selma” “fiction.” As in: “film and other fiction.” To her, apparently, film is always fiction. But it’s not.

Like books, film is a medium.

Film can be nonfiction.

Film can be fiction.

“Califano’s approach,” she writes, “besides setting a odd standard for how fiction ought to work…suggests that we should check fiction for inaccuracies.”

As usual, the crux of the debate boils down to an inability to agree on definitions of terms. For those like Rosenberg who believe that everyone knows movies are just for fun, it doesn’t matter that “Schindler’s List” depicts showers at Auschwitz spraying water rather than Zyklon B — even though that never happened, and thus serves to understate one of the horrors of the Holocaust. To the all-movies-are-fiction crowd, “Zero Dark Forty” is cool despite its completely false claim that torture led to the assassination of Osama bin Laden.

“This is art; this is a movie; this is a film,” director DuVernay told PBS. “I’m not a historian. I’m not a documentarian.”

That’s sleazy. Truth is, her film is being marketed as fact, as she knew it would be. And it’s doing better because of it.

Audiences need a ratings system to separate films that purport to recount actual historical events from those like “Selma,” which are fictional tales using historical figures as hand puppets.

I suggest that the MPAA institute the following ratings:

Rated H for Historical: a film that makes a good faith effort to recount history accurately.

Rated S-H for Semi-Historical: a film that relies on devices like made-up dialogue and encounters, but whose basic plot line reflects history to the best of our knowledge.

Rated H-F for Historical Fiction: a film in which anything, including the basic plot line, can be made up out of whole cloth.

If the movies are going to lie to me, I deserve to know before shelling out my $12.50.

For aNewDomain, I’m Ted Rall.