aNewDomain — Nationally, we have race problems. A stack of them. Are we making progress? Nationally, maybe. As individuals, though, we can kind of see where authors and screenwriters are, race-wise, by how much risk they are willing to take with their characters.

aNewDomain — Nationally, we have race problems. A stack of them. Are we making progress? Nationally, maybe. As individuals, though, we can kind of see where authors and screenwriters are, race-wise, by how much risk they are willing to take with their characters.

Can you make your characters evil? Or are you afraid to?

Dean Koontz included a man with Down syndrome in his novel, The Bad Place. I’m very much in favor of including everyone it makes sense to include, and I am in no way criticizing that choice. But it does say something about Koontz’ disability acceptance that his character is magical. The guy is a psychic, an idiot savant in the old sense, blessed with insight because of his lack of sophistication. He is a holy fool.

I know lots of people with this condition, and I am of an age when intervention was usually limited to shutting them up in an institution and forgetting about them. This would happen to people who are stubborn sometimes to the point of violence, non-verbal, who often need help with basic eliminatory functions.

People would come to work for our agency that helped people with these conditions, thinking they would meet the sweetly retarded, magical people in movies and books. They didn’t last long.

Everyone has traits good and bad, desirable and not, lovable and more challenging. When we idealize a person, we strip them of personhood. It takes an effort, sometimes, to love people who need you and, simultaneously, don’t want you around because they’ve had to say goodbye to so many people who they needed.

Or take Will Smith in “The Legend of Bagger Vance.” He is cast as a magical black person who knows everything about golf and helps Matt Damon win.

When you can make your diversity of characters all equally good and equally evil, it is more likely you’re telling a real story, a story that’s true regardless of the fictional quality of its facts.

When you have to idealize certain kinds of people, you’re more likely trying to sooth your own troubled conscience.

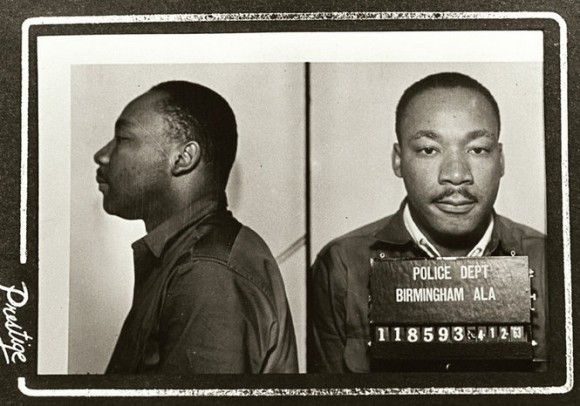

Take the way we deal with Dr. King. We idealize the man, forgetting or forgiving his indiscretions, paying no mind to the morally difficult choices he made – skipping over one protest because another would look better on film; withholding support from one demonstrator or victim because their past, for probably racist reasons, wasn’t quite clean enough for the white media.

He was still a hero, still deserves all those schools named after him; but he was just a mortal man, like you and me. No special holiness caused him to do what he did. That means you could do it, too, if you wanted to.

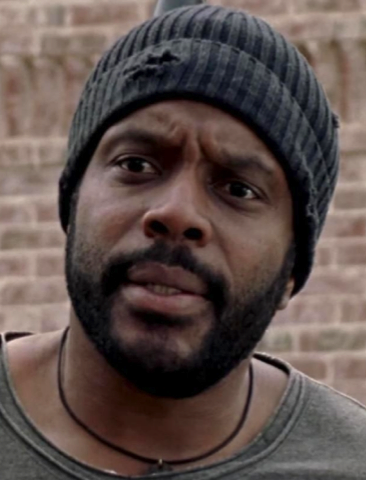

We can observe this progression in The Walking Dead. Let’s start with T Dog.

T Dog had almost no speaking lines in season 1. His purpose was somewhere between tokenism and being a foil. He was the black cast member but, perhaps more importantly, he set up Merle Dixon as the villain.

Because T Dog was there, Merle had a reason to speak his most racist lines. Without Merle, his comparatively mild treatment of Glenn would present too subtle an evil. Later in the series, when Tyreese joined the show, fans started the sort of running half-joke that only one black man was allowed on the cast at one time. T Dog suddenly got a soliloquy and then died, and we also learned that when someone who almost never had lines got a long speech, that was their exit.

And really, without that speech, who would have cared about T Dog dying? He brought no skill, no dialogue, no hopes or dreams to the story – a failure of the writing.

And really, without that speech, who would have cared about T Dog dying? He brought no skill, no dialogue, no hopes or dreams to the story – a failure of the writing.

Tyreese brought complexity.

Physically he fit a particular stereotype but mentally and emotionally his complexity made him beloved by fans. He was good, good to a fault. He despaired over the state of things, trying to internalize Bob Stookey’s philosophy of unconditional happiness and, ultimately, failing. He wouldn’t kill. In the end, he died without really violating any of his personal ethics.

A step forwards: A black man with real lines, real emotions, depth and complexity. But still too idealized. The idealized character can be seen as acceptance and processing of the tokenism of T Dog.

More progress, and progress that really makes the show watchable now, is Father Gabriel.

Gabriel is a coward. He harbors evil in his heart even while he stands at the front of a church. His actions led to the deaths of his parishioners: he locked up the church and pretended he wasn’t home as the first waves of the apocalypse rolled through town. When Rick and his crew found Gabriel Stokes, he was all alone with his church as a fortress.

Black people aren’t all cowards but Gabriel is not all black people. That’s the point here. The first two black characters on the show (excluding the transient ones like Morgan), the ones part of the crew, were either marginalized or idealized.

Perhaps a perception that each black character must stand for one’s attitudes towards all black people informs the way these characters are scripted.

But black people are, first, people. With hopes, dreams, ambitions, and sometimes dysfunctional ways of coping with the world.

When you can’t make your characters good or evil according to their individual needs or the needs of the story, you risk stereotyping – either positive or negative, these are equally harmful. Tyreese was nearly not a person but a saint, a spirit.

It is when anyone could do anything, when your characters are not predictable because of their color or gender, that things get really interesting.

Think of it like a George R.R. Martin story. In book 1 of Game of Thrones, he kills the best character in the story – the most morally wholesome, conflicted character, the one you thought was driving the whole plot.

Think of it like a George R.R. Martin story. In book 1 of Game of Thrones, he kills the best character in the story – the most morally wholesome, conflicted character, the one you thought was driving the whole plot.

He did it on purpose. It was a statement: Everyone is at risk here.

If you can’t do that, what’s the point in writing? If you won’t kill off your story’s children or people of color or women, if you won’t make the autistic guy the bad guy for fear of offending someone, then why bother? We all know the outcomes in advance. They’re the sainted sorts of outcomes that don’t really happen in real life.

In real life, people are deep. Even the shallow ones, yeah, and even the ones who never let on. If you have trouble writing diversity, consider whether you have a deeper problem with diversity. Like, maybe you go to an all-white church in an all-white neighborhood, and you should consider getting out more.

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

Cover image: IMDb.com, All Rights Reserved; inset image one: huffingtonpost.com, All Rights Reserved; image two: Christian-Miracles.com, All Rights Reserved; image three: TheCatholicCatalogue.com, All Rights Reserved; image four: undeadwalking.com, All Rights Reserved.