aNewDomain — Evidently I get good ratings on RateMyProfessor.com.

aNewDomain — Evidently I get good ratings on RateMyProfessor.com.

Today, some of my students tried to tell me how good my ratings were. They were surprised when I said I preferred not to know about it. “But they’re all good!” they said.

Even good ratings can be bad, though.

Online ratings have a self-selection bias.

Here’s the first problem: Online rating sites carry a well-known bias. It’s called self-selection. People only take the time out of their day to rate products and services if they’re really motivated to do so. And usually that’s because they either  really loved or really hated an experience. So you find a lot of five-star ratings and a lot of one-star ratings, but rarely anything in between.

really loved or really hated an experience. So you find a lot of five-star ratings and a lot of one-star ratings, but rarely anything in between.

In other words, a lot of good ratings doesn’t mean I’m a great professor. It really just means nobody cared enough to damn me with faint praise.

Not everything is rate-able.

Here’s the next problem, and the one that makes me so wary of this site: College instructors are not commodities or services amenable to such ratings.

I don’t, for starters, owe students a good experience.

I owe them honesty and integrity, promises made and kept, and fairness. That’s it. It isn’t my job to entertain people, make dull material interesting, or cater to every person’s individual beliefs and worldviews.

Secondly, I don’t owe students good grades. I owe straightforwardness and a certain amount of pedantry, as in: No, sorry, 88 is not 90. You’ve got a B, not an A.

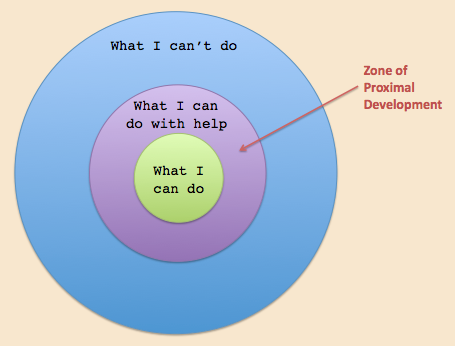

I do owe students a challenge. The work should always be just a little bit beyond what students are capable of or comfortable with, forcing just a bit of a stretch.

I do owe students a challenge. The work should always be just a little bit beyond what students are capable of or comfortable with, forcing just a bit of a stretch.

I owe them a chance at growth, in other words.

But I’m not that interested in what my students think of me. They keep coming back to take more advanced classes, and I like that.

I also worry that places like RMP might promote a certain amount of trolling.

What about trolls?

If someone were to complain, that could follow me around. When I apply for faculty positions elsewhere, maybe the search committee looks at RMP as a matter of course. Who wouldn’t? But there doesn’t seem to really be a process of establishing if these are even real students of mine, or certainly that their beefs are legitimate.

Profs do sometimes engage with the feedback they get over there. And I worry about that, too. See, websites make money through traffic. The more traffic you get, the more you can monetize.

Any why should an online ratings site be able to make money off the back of my labor?

Now, I owe some things to students but I definitely owe nothing at all to potential students shopping for teachers. I owe less to websites attempting to make money on the back of my labor. I never consented to this.

When profs engage with feedback, now there’s a conversation. Comments sections are fantastic for traffic but are little more than mosh pits for Internet trolls. I have to assume this particular mosh pit is regulated. But how can you be sure?

And everyone who logs in to provide more content is giving RMP free content, which means more hits and more dollars for the site. When did I become a marketing guy? I don’t care at all about online ratings or the sites that host them.

My last concern and maybe the biggest one is this: Students are not customers.

In the 1990s, under ISO standards, we were all encouraged to work out who our customers were and whether we were serving them appropriately. And in a lot of places, students got identified as the end customer of education.

In the 1990s, under ISO standards, we were all encouraged to work out who our customers were and whether we were serving them appropriately. And in a lot of places, students got identified as the end customer of education.

That’s a horrible mistake.

Students are stakeholders inasmuch as what we do affects them. And I hope we affect them profoundly. But it isn’t like students are showing up to a buffet, taking what they want and paying for it. They’re coming in to be evaluated on behalf of a society that needs morally upright, critically thinking educated professionals.

I serve in many capacities in this process. As a gatekeeper: You may pass, you may not pass. As a mentor. As a role model — but, oh god, please don’t let them all make me their role model.

I’m also a sounding board, teacher, editor, educator. But I’m not a service provider.

College isn’t another fast food restaurant.

College isn’t McDonalds. You don’t get to always get what you want, and you can’t be mad like when there are pickles on your burger and you specifically asked for no pickles.

My job in many of the roles I fill is to disappoint people. This paper doesn’t meet the stated requirements. These answers are not correct. This behavior is not appropriate to the classroom setting. These deadlines have passed. I am glad you prioritized funerals or medicine ahead of grades, and you did that, and now your grade is lower than you want. Sorry. But trust me, it’s worth it.

So, good ratings or not good ratings, I don’t like what’s happening here.

Online ratings are a fact of life in the Internet age, true. Maybe we all have to live with them.

And yes, I never signed on to be commodified or have my teaching methods discussed in public. But ultimately it’s a small enough burden to bear, overall.

I do worry that we’re giving students lots of good reasons to commodify professors and education generally. For-profit schools certainly have encouraged the trend toward thinking of students as customers (more as commodities themselves, cows to be milked for their education benefits or student loans then left by the wayside to repay those loans later). This results in the changing of curriculae to be easier and more accessible, which leads to graduates possibly being rejected later because of a lack of adequate preparation or skills.

And education is so much more expensive today than it was 40 years ago or even when I went to college. It’s gotten so much more expensive that it hurts to even think about. We help less and less with subsidies and grants, state funding, and tuition assistance programs, which makes the student really seem to be the customer. In the modern world, students have paid for a dramatically higher percentage of their educations than society has overall.

So don’t they, in the end, own those educations?

Maybe I should rethink my stance against students as customers and online ratings in general. Maybe I really do owe everyone an A, a nice time and some gentle reassurance that their medieval ideas are every bit as good as anything they derive from critical thinking.

Think about it.

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

Image one: Personal.PSU.Edu, All Rights Reserved; image two: AYoungerTheatre.com, All Rights Reserved; image three: InnovativeLearning.com, All Rights Reserved; image four: FactsExplosion.weebly.com, All Rights Reserved.

I am also a professor and just checked my rating at RPM — B+ — but it was a small sample and two people hated me. On our campus we also have student ratings for each section, so the sample is much larger, but your obserrvation holds true there also — mostly 5s a few 1s and few in the middle.

I heard a presentation at the EDUCAUSE conference a few years ago by the people who analyze student evaluations at a university in the south (but I don’t recall which one). Their approach was to focus on the ratings that were not 5 or 1, but between. They reaonsed that those people would have put more thought into the feedback.

They did not pay attention to the ratings themselves, but to the supplementary comments on those in-between evaluations. I do the same and find those comments helpful and valid at times.