aNewDomain — Culture has always been class-based. Rich people went to the opera; the poor listened to heavy metal. But what we read and watch and listen to is becoming segmented into more striations with wider gaps between them, reflecting income distribution.

aNewDomain — Culture has always been class-based. Rich people went to the opera; the poor listened to heavy metal. But what we read and watch and listen to is becoming segmented into more striations with wider gaps between them, reflecting income distribution.

I was thinking about this while reading that ultimate periodical for, by and about the richest one percent: The Sunday New York Times.

The Times is historically elitist: You get lots of reviews of classical music and fine arts, hardly anything about rock, hip-hop or comics. In Timesworld, a $150 dinner qualifies as a moderately expensive meal. A $650 hotel room is something you might actually consider.

But recently I’ve noticed that the gaps between what the Times prints to try to attract the audience targeted by its advertisers and the interests and tastes of most of its upper-middle-class striver readers are getting more pronounced. Just this weekend, I was tearing through the Sunday edition. (Despite lower page counts, it is still a whale of a paper.) I did it in under an hour.

The Times doesn’t have many pieces I want to read anymore.

The Times doesn’t have many pieces I want to read anymore.

The paper was always a pretentious publication. Now it’s pretentious and blah. The Times delivers too many puff pieces on corporate executives, too many political horserace articles minus actual politics and way too many dreary profiles of boring authors, musicians, etc.

But the really big change in The Times? It’s the tone of the stuff they print.

Good writing draws you in no matter what the topic. A decade or two ago, you could count on The Times, more so than The New Yorker and The Wall Street Journal, to print words strung together in a way that would make you care about anything from asparagus cultivation to arbitrage. Now, not so much. Everything in there reads like it was written by a pod person on a triple dose of Prozac.

The Times is all flat-line affect.

Which, in a way, is interesting — interesting in a dull way but still interesting: You see, to make it as a successful journalist in 2015, you have to be able to make videotaped mass beheadings dull.

This is, in a way, a skill. But who has time to read it?

So, today I read The Times in a slow-down-to-check-out-the-car-wreck way. And I came across an item that brought home the widening cultural class divide. Here it is:

So, today I read The Times in a slow-down-to-check-out-the-car-wreck way. And I came across an item that brought home the widening cultural class divide. Here it is:

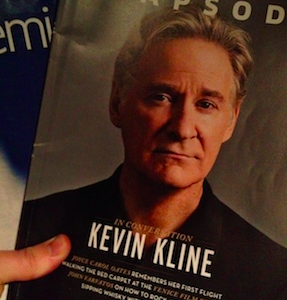

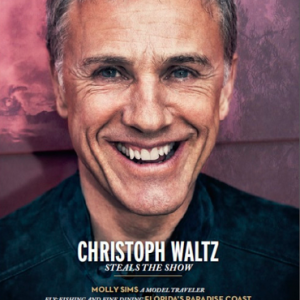

Breaking News! United Airlines has a new in-flight magazine, but it’s only for those who pay top dollar for flights. And it only features the type of literary fiction Timesians like long-time book critic Michiko Kakutani classify as “high-end.”

Good God.

Reports Alexandra Alter:

“As airlines try to distinguish their high-end service with luxuries like private sleeping chambers, showers, butler service and meals from five-star chefs, United Airlines is offering a loftier [get it? me, I think puns are low-brow but whatev], more cerebral [read: boringly pretentious and/or pretentiously boring] amenity to its first-class and business-class passengers: elegant prose [see previous bracketed phrases. Not by prominent novelists like best sellers James Patterson or Stephen King, but the Times-approved cadres whose covers grace the front windows of your local ‘independent’ bookseller.]”

Alter continues, “There are no airport maps or disheartening lists of in-flight meals and entertainment options in Rhapsody.”

Alter continues, “There are no airport maps or disheartening lists of in-flight meals and entertainment options in Rhapsody.”

But wait. Rich people don’t need airport maps? How do they navigate airports — teleportation?

“Instead,” she writes, “the magazine has published ruminative first-person travel accounts, cultural dispatches and probing essays about flight by more than 30 literary fiction writers.”

She reports a list of authors that includes “literary stars like Joyce Carol Oates, Rick Moody, Amy Bloom, Emma Straub and [Anthony] Doerr, who won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction two years ago.”

I’m glad I’m in Coach. Every one of those writers bores the shit out of me.

To paraphrase the fictional Nazi in Hanns Johst’s play via Mission of Burma, whenever I hear the phrase “literary fiction” I reach for my revolver. Then I run away screaming.

Fiction is good or bad. There is no such thing as non-literary fiction.

Purveyors of literary fiction sometimes wonder aloud why their non-genre genre doesn’t get more attention (from the marketplace). Though I infrequently observe a relationship between quality and sales, I can answer this question: literary fiction is written for an upper crust, very white, well-educated but not-as-smart-as-they-think sliver of the word-consuming public — whose number is too small to create a Stephanie Meyer-scale bestseller.

Purveyors of literary fiction sometimes wonder aloud why their non-genre genre doesn’t get more attention (from the marketplace). Though I infrequently observe a relationship between quality and sales, I can answer this question: literary fiction is written for an upper crust, very white, well-educated but not-as-smart-as-they-think sliver of the word-consuming public — whose number is too small to create a Stephanie Meyer-scale bestseller.

Ninety years ago, these would be the same people who hate Hemingway.

They hate anyone just for writing non-MFA approved sentences that anyone could read, understand, enjoy — and not notice.

To paraphrase Mark Twain, who argued that any library would be improved simply by the absence of any books by Jane Austen, I will endure United’s cramped coach class more stoically thanks to my awareness that there isn’t a copy of Rhapsody in the seat pocket in front of me.

The Times, again:

A United marketing flack ‘said the quality of the writing in Rhapsody brings a patina of sophistication to its first-class service, along with other opulent touches like mood lighting, soft music and a branded scent.’ “

Gag me with a plastic TSA-approved spoon.

But wait, there’s more …

‘We’re not going to have someone write about joining the mile-high club,’ said Jordan Heller, the editor in chief of Rhapsody. ‘Despite those restrictions, we’ve managed to come up with a lot of high-minded [pun alert!] literary content.'”

Listen. There was a time, not long ago, during my own young adulthood, back when upper middle class and upper class people read the same books and magazines. The former aspired to the latter; the latter imagined themselves in touch with the former.

Now there’s literary fiction, a category designed as an exclusion.

In music, this is jazz. In movies, it’s documentaries and art films. It’s NPR and The Times and the Democratic Party.

Today, the rich live in gated communities of the mind. Every house and every person inside them look and talk exactly the same. No weeds on the perfectly manicured lawns.

Just boring, bland, flat bullshit.

As much as they work to keep us out, I know what keeps the cultural one percenters awake at night: Their very real fear that we don’t want to get it.

For aNewDomain, I’m Ted Rall.