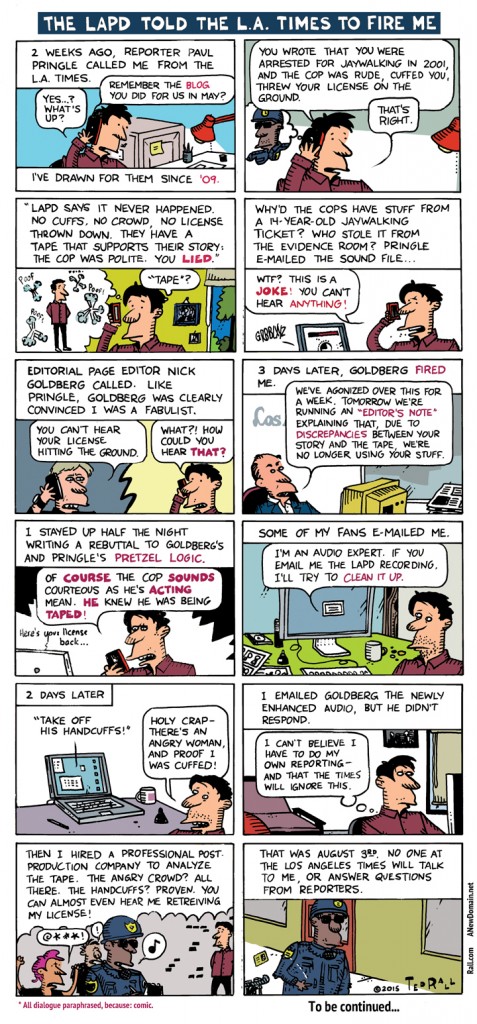

aNewDomain commentary — When The Los Angeles Times told me it had doubts about an Opinion Pages blog I’d written for them I was worried. The LAPD, which hated my many anti-LAPD cartoons, had given my editors a tape that purportedly showed that I’d lied in the piece.

— When The Los Angeles Times told me it had doubts about an Opinion Pages blog I’d written for them I was worried. The LAPD, which hated my many anti-LAPD cartoons, had given my editors a tape that purportedly showed that I’d lied in the piece.

But nothing prepared me for what came next: The Times published an “Editor’s Note” that told the world, in print and online, forever to come, that I was a liar.

My friend, a fellow cartoonist, was furious. “The nuclear option!” he yelled. “I can’t believe it!”

I was lucky. I was able to prove I wasn’t a liar. But …

Even after this publication and I paid for — and posted — an audio-enhanced version of the tape that proved I hadn’t been lying, the newspaper refused to admit they messed up. Instead, management doubled down. Now my case has become the focus of a controversial debate about police and state influence over a free press.

Instead, management doubled down. Now my case has become the focus of a controversial debate about police and state influence over a free press.

Outside the shrinking population of professional journalists, few people know how allegations of ethical breaches by reporters get handled. So here’s an overview of how a typical newspaper editor responds to a case like mine, involving an alleged breach of journalistic ethics.

My troubles began when someone in the LAPD or LAPPL police union slipped a secret audiotape of my 2001 jaywalking arrest to someone at the Times. (The Times is refusing to answer questions, so we don’t know who gave it to whom.)

What would most editors do in the same situation?

My colleague Gina Smith is a longtime newspaper journalist and has written columns, articles or been on staff for a half dozen of the nation’s big metropolitan dailies. She called around. Not surprisingly, given all the flap around my scandal, almost all the editors she contacted refused on-the-record comment. However, a few did comment on the record, but on the condition of anonymity.

They all said they would be careful.

“I would have to investigate,” one editor-in-chief from a large West Coast daily told Gina when asked what they would do. “Even if the tape had been clearly audible, I would’ve had to have brought it to the editorial board. Especially if it was well-known that the police disapproved of this columnist’s coverage.”

Another editor-in-chief we interviewed is with a large Midwestern metropolitan daily. This editor also requested anonymity, but said:

“I would have wanted a lot of information before I would have signed off on the first-person column – especially knowing of the past controversies with my columnist and the police department,” she told aNewDomain.

And if the piece was approved, and ran — and then the police approached with a tape intended to discredit the writer? “I would request a meeting with law enforcement officials and my columnist – and perhaps, the company attorney – to (examine) the incident on tape.”

“I would write a news story about the situation and the claims,” she added, saying that story would quote “both my columnist and law enforcement. I would post their (tape) – which should be considered an Open Record since it isn’t part of an ongoing investigation – online for readers to judge for themselves. If I determined that there wasn’t enough evidence to refute my columnist’s claims, I would not take any action.”

In most newsrooms, the source of the tape (the LAPD) coupled with its object (a cartoonist known for anti-LAPD cartoons) would make editors wary, our sources said.

Given the clear political motivation for the leak and its inconclusive content (6 minutes of static out of a 6 minute 20 second tape), odds are that I would never have heard about this dubbed audio — copies of recordings are impossible to authenticate and are thus inadmissable in court — in this “he said/he said” story.

Escalating beyond a shrug would typically require stronger evidence that I’d violated journalistic ethics. What if there had been a “smoking gun” on the LAPD audio tape — something that seemed to point to a clear, intentional lie in my work, about something more meaningful than a minor detail (gutter vs. sewer)?

That wasn’t the case here.

But if it had been, the next step for a careful editor would be authentication. The audiotape, whose provenance was inherently highly suspect, would be sent to a reputable scientific lab to check for signs of tampering and manipulation. But that would require the original micro-cassette, as well as the recorder used at the time. There is no evidence that the Times has the original, or that it still exists.

As we know, the Times — which had already jumped past the “shrug” stage into treating the copy as meaningful — took another leap, taking the police at their word when they said the tape was okay.

If the recording had been deemed to contain substantial cause for alarm (which it wasn’t) and then proven to be legit (which it hasn’t), the next step would be to bring me in to tell my side of the story to the editorial board. This would be the Very Serious Stage, when your job is on the line. Most editors would want the cover of a group decision, as well as the benefit of multiple points of view in considering an action as grave as declaring a journalist guilty of an ethical breach (such as, say, plagiarism).

Now let’s assume that the editorial board had arrived at a consensus that yes, I had wrongly called the LAPD officer rude and unprofessional in my May 11th blog. What next?

Two points you should be aware of: Generally speaking, opinion pieces are allowed more latitude than straight news.

And: Online blogs, even about news, are not held to the same standards as straight news.

Given that this was an online opinion blog, and the facts in question concern a personal anecdote, even a solid determination that I had lied would have been highly unlikely to have resulted in the “nuclear option” at most papers.

I might have received a stern warning.

Further escalation?

Perhaps an “Editor’s Note” explaining to readers that the LAPD disagreed with my account.

Worse? They could have suspended me, pending a detailed investigation (such as checking out the tape). That’s what NBC did to Brian Williams, before bringing him back, but to MSNBC.

The big bomb? They could have told me I was fired, and for lying, without printing anything. I might have had a case for wrongful termination in a court of law, but there wouldn’t have been a defamation issue.

What they actually did — the nuclear option — is virtually unheard of in American newspapering, even for grave offenses like plagiarism. Instead of investigating, the Times took less than 24 hours to decide to let me go. They didn’t let me speak to the editorial board, which did not meet to discuss my case. They didn’t have me confront the LAPD. They didn’t make any attempt to authenticate the tape — which, we now know, cannot be authenticated, and when enhanced confirmed my account rather than the police’s.

Given the fact that I wasn’t guilty of anything — no lie whatsoever — the chasm between an appropriate response and what the Times did instead is astonishing.

For aNewDomain, I’m Ted Rall.

Additional reporting by Gina Smith.