aNewDomain — I am a lover of fiction. As both a reader and a writer, I spend a lot of time thinking about the state of reading in America. Is digital access to media eroding our connection to the paperback novel? Has the constant buzz of news feeds impacted this nation of idealistic dreamers? Is it still important to sit down and read a fictional story?

I ponder these questions lying in my bed before I turn off the light. On any given night there’s a 50/50 chance I’ll be perusing my news feed or plowing through another Gaiman novel. I think about these questions on BART, where far more than half of the commuters and tourists are staring intently at their mobile device of choice rather than a book or a magazine.

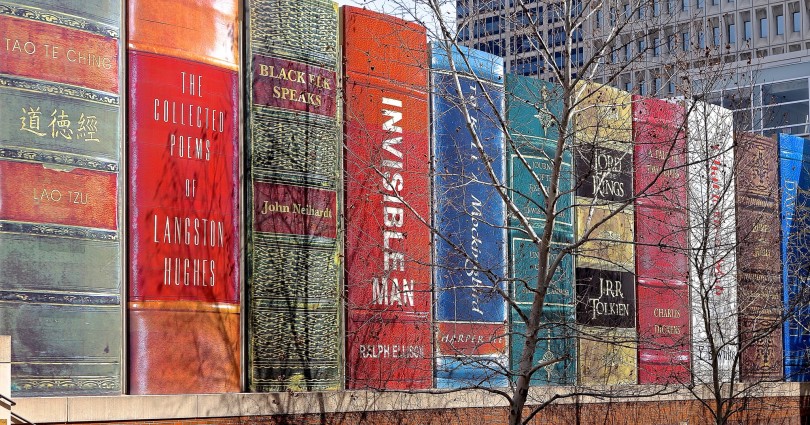

In my opinion, reading is essential. Particularly, the reading of fiction. We need fiction to feed our creativity, tell our brains to relax and to allow us to step into a different world. Don’t we all crave those things? Even so, I don’t think I’m alone in fearing that at this point, our society might not be geared toward them any more.

Paper vs. Digital

Are e-books changing everything about book consumption? Yes, they are.

Are e-books changing everything about book consumption? Yes, they are.

Historically, humans used the oral tradition to tell stories and to describe events — both true and untrue. Think back to how Herodotus’ histories were collected or how epic poems like “The Iliad” and “The Odyssey” were amassed. Over time, these and many other stories were captured in writing. Fast forward to the advent of the printing press and publishing houses in London and New York and you can see that we have moved through two different periods of time which encompass the ways we shared information with one another.

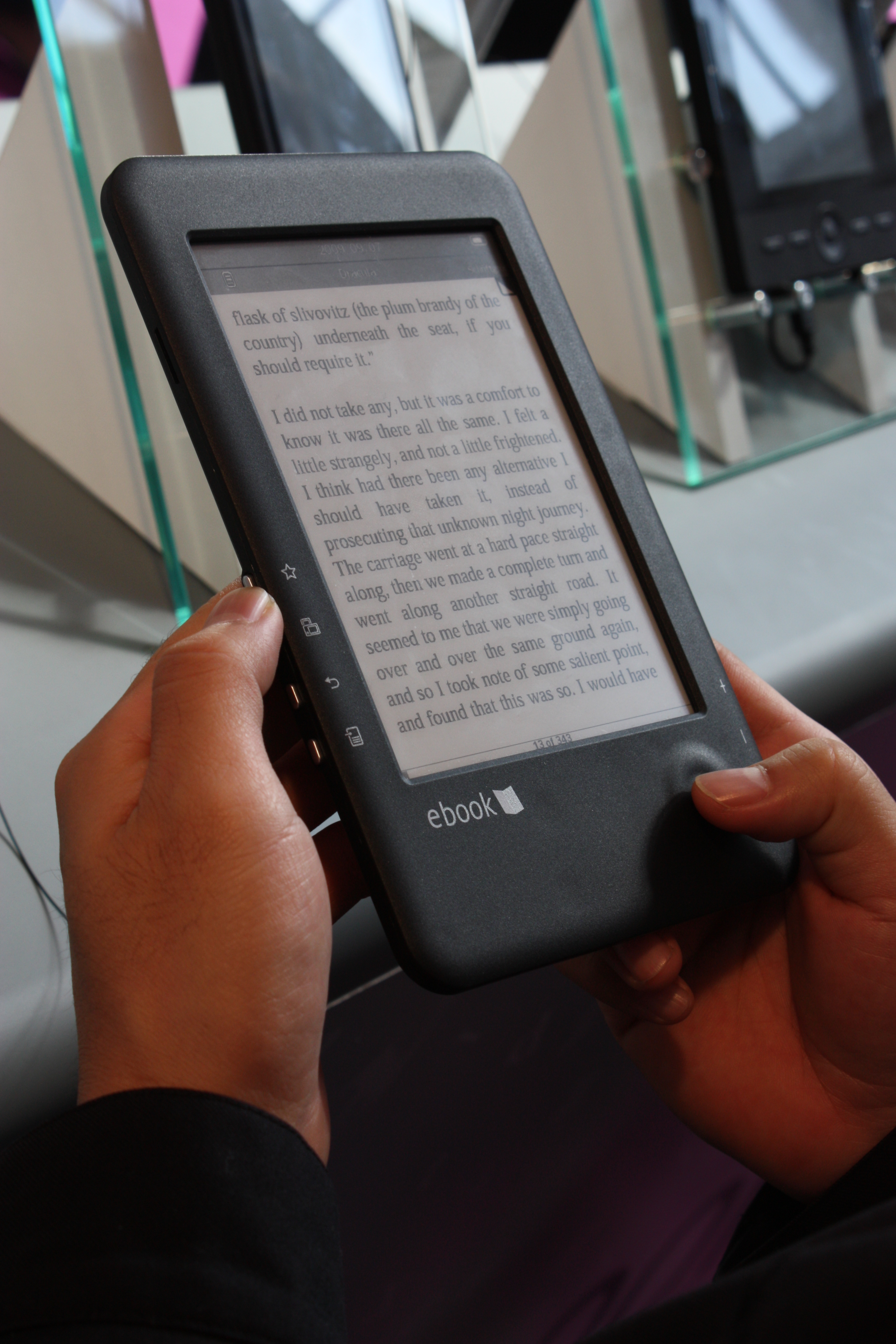

E-books mark the start of a new age in news and in literature. While similar in many ways to traditional physical publishing, the e-book and other forms of e-text changes how we access the information. Our text is now searchable, interconnected and on-demand immediately. This is not to place value on e-text — it’s not necessarily better or worse — but it is fundamentally different.

The real issue with e-books is not the text itself, but the devices on which you can read the text. Kindle or iBooks might display beautifully and search quickly while an app like Oyster gives you access to literally hundreds of thousands of books, but all of them require a smartphone, tablet or computer. And those devices have a huge number of other apps, just a click away, which can take consumers from the well-crafted world of words to a movie, TV show or stream of social news.

Moshin Hamid said in the New York Times,

“E-reading opens the door to distraction. It invites connectivity and clicking and purchasing. The closed network of a printed book, on the other hand, seems to offer greater serenity.”

If you constantly read on a device, it means you could also be watching TV, checking the news or scrolling through cat memes (see what I did there? Distraction).

How can we expect to engage fully in literature if the temptations of the world are at the same fingertips that scroll across those digital pages? And if we don’t engage fully — due to overstimulation, lack of self-control or minor techy addiction — we won’t fall into the imaginative world of literature as quickly.

The News Feed

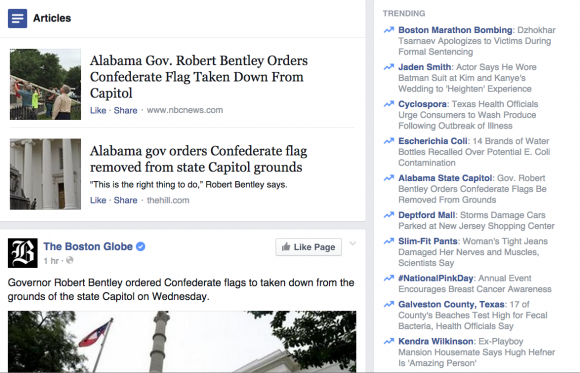

The most distracting of all these device-based entertainments is the news feed. I remember when the Facebook feed first rolled it out — my homepage was no longer my profile page, it was endless information about everyone I knew. As the feed progressed (and spread to every other social sites) ads, links and news stories began to fill the space.

The most distracting of all these device-based entertainments is the news feed. I remember when the Facebook feed first rolled it out — my homepage was no longer my profile page, it was endless information about everyone I knew. As the feed progressed (and spread to every other social sites) ads, links and news stories began to fill the space.

I have two issues with the news feed. First, it enables a culture of brief, momentary encounters. Gary Vaynerchuk, an entrepreneur in e-commerce, gave an educational lecture at No Film School. He said,

[I spend my time] figuring out how to story-tell in micro-moments. [We] live in the greatest ADD culture of our time, [we] have absolutely no time. I’m obsessed with the notion of how do I tell you my story, when you take out your phone, and you do this.”

The “this” he’s describing is the endless smartphone finger scroll. While Vaynerchuk is completely right — to get your story or point across in today’s world, you must adapt to the news feed — I don’t see this is a good thing. This mentality further empowers our brief, ADD attitude toward all forms of media, and makes full concentration (on something like a novel) more and more challenging.

The second issue I have is that while the news feed seems to present a wide variety of endless information, the algorithms currently in place actually make the rapid cycle very closed. Not only does the feed show so many competing stories that the brain can’t possibly (and doesn’t want to) delve deeply into a single one, but it quickly becomes a curated version of the world.

And, music and film-trailers aside, the articles that tend to surface for everyone are about police brutality, political mishaps, crazy recipes and celebrities. Sure, you can control and block certain content, but how many of us do that? Rarely are the trending topics about a great piece of literature you can read, for free, at that very moment. If that did pop up, would anyone take the time to do it?

The Decline of Reading

The National Endowment for the Arts conducted a study called “Reading on the Rise,” which measured American literary reading habits over 26 years. It showed that between 2002 and 2008 reading of fiction rose on a national level. It deemed this success to many factors, but mainly to a strong governmental and school-wide push to increase literary interest in the youth.

And, for those six years, it worked. Since 2008, however, the number of fiction readers have dropped to 46 percent, the same number as in 2002, and the lowest number the country has had in the last 30 years.

Quentin Fottrell of MarketWatch lists a number of reasons. He cites the rise of autobiographies and self-help books (still reading, but not fiction), social networking’s lack of fiction promotion and downright narcissism. He says,

Americans may be more fascinated with their own lives than with those featured in great works of literary fiction: Some 56 percent of Internet users have searched for themselves online, such as by typing their own name into Google, according to the Pew Research Center. Studies also show that people’s attention spans are getting shorter.”

While each of those points is valid, I think the desire and accessibility for apps and smartphones has played a role as well. The iPhone was released in 2007. Apps have grown so tremendously from 2008-2012 that entire industries and full-fledged economies have exploded in the U.S. And with all that great, life-changing technology, our national reading went down.

PEW Research shows that tablets and e-reader ownership is continually on the rise, and while that does mean people read books and care about reading, it also means their method of reading is more closely connected to the news feed and a hundred other distracting apps.

What Fiction Can Do For You

So, you might wonder at this point, why is fiction so important?

So, you might wonder at this point, why is fiction so important?

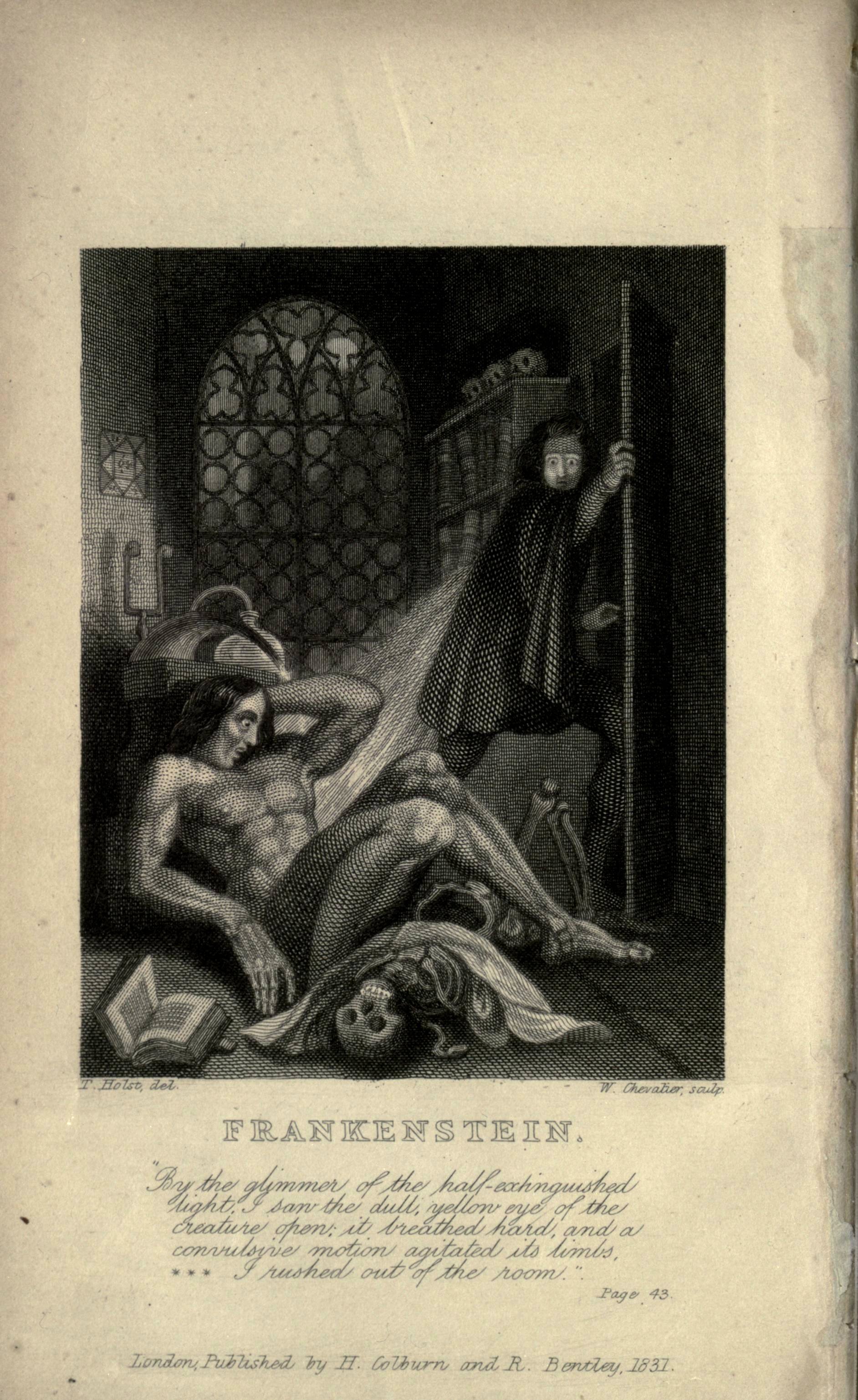

A couple reasons. A study released by psychologists showed that reading literary fiction — like Charles Dickens and Anton Chekov — can increase your empathy. In figuring out the complex character motives involved with reading great literature, the study claims, we can actually better understand humans around us.

It’s ironic that social networks may actually pale in the development of human understanding and connection when compared with reading great literature.

But it’s more than that. Fiction lets us see new worlds — worlds that are separate from this incredibly fast-paced reality. Worlds that are unique and abundant and true in their own way.

If we are so focused on tiny snippets of news that cycle endlessly and only depict the current state of affairs, how will we create something new? Innovation is the hottest tech trend out there, but I believe we must take the time to fully enter another perspective in order to create anything unique.

For aNewDomain, I’m Daniel Zweier.

Ed: The original version of this article ran in aNewDomain’s BreakingModern. Read it here.

Images in order: Library by Dean Hochman via Flickr; IFA 2010 Internationale Funkausstellung Berlin 65 by Bin im Garten via Wikimedia Commons; Screenshot by Daniel Zweier; Frankenstein.1831.inside-cover via Wikimedia Commons