aNewDomain — I am not a game theorist or an economist, but it’s pretty obvious that the work of Jean Tirole, who nabbed the 2014 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, applies perfectly to two Silicon Valley arenas. The first is the so-called two-sided market. The other is the regulation of one-sided marketplaces like those dominated by monopolies and oligopolies.

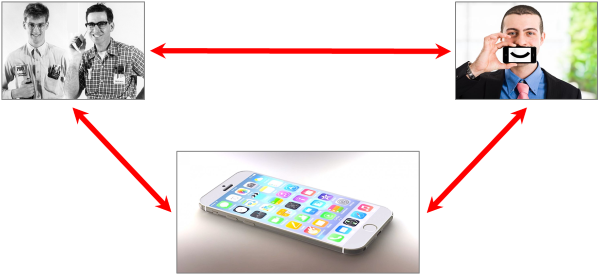

The Apple iPhone is an example of a product with a two-sided market. Apple sells iPhones to end users and also profits from app sales by developers. In Econ 101 we learned that a company maximizes profit by setting a price at the point where marginal cost equals marginal revenue. But that’s too simple for this example. The iPhone is at once a consumer product and a for-sale development platform.

Apple wants to attract application developers as well as sell iPhones, and the more iPhones it sells the more attractive the platform is to developers. Winning more developers means more apps, which means more revenue for Apple, and it also makes the iPhone more attractive to end users. So the optimal price for an iPhone is not the point at which marginal cost equals marginal revenue. Rather it equals something lower.

Apple and its two-sided market

The Apple iPhone is a product for consumers and a platform for developers. That’s why its optimal price isn’t obvious.

Google’s optimal pricing is an extreme example of this sort of thing. Google supplies search and other services to end users, and it sells ads to businesses. The more services it supplies, the more it learns about its users. Correspondingly, the more valuable it becomes to advertisers. This how Google became an edge case: It prices consumer services at zero, relying solely on revenue from advertisers. On the other hand, it charges businesses $50 per user per year for Google Apps for Work, which is $120 U.S. with unlimited cloud storage.

The business services offer a few extra management features, but the marginal cost for a new user is essentially the same.

Why the price difference? Business users are able to turn off ads, and Google doesn’t scan business emails to gain intelligence. This is a one-sided market.

Now consider Google apps for education. The service is free and it isn’t ad-supported. Google gives schools a break, presumably, because it’s betting that post graduation, students used to Gmail and Google Drive applications will keep using them. That generates a long run profit for Google. (Google sure doesn’t earn a Nobel Prize for this idea. When I worked for IBM we gave universities an 80 percent discount on computers for pretty much the same reason.)

Tirole and his co-author, Jean-Charles Rochet, give many more Internet-related examples of two-sided markets in this paper. The mini case studies in the paper are straight-forward but the mathematics is chewy. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

On one-sided markets: monopolies and oligopolies

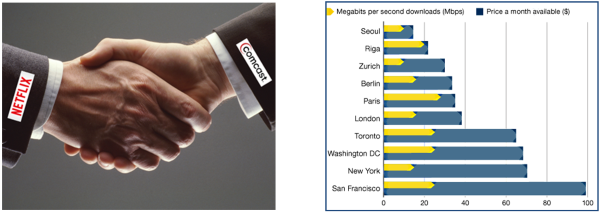

U.S. ISPs like Comcast are able to charge content providers delivery fees and set high prices for end users.

In awarding the prize, The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences lauded Tirole for clarifying “how to understand and regulate industries with a few powerful firms.” That sure sounds a lot like the network industry, a one-sided market if ever there was one.

In the United States we have two regulatory conundrums. The first problem involves consumer pricing. Consider that the incumbent telephone and cable TV companies own the “last mile” infrastructure connecting homes and offices to the Internet. This is what enables these behemoths to set such astronomical prices for end users. The second is the problem of getting network operators to invest in infrastructure.

Let’s look at investment infrastructure first. Joshua Gans, a professor of strategic management at the University of Toronto with close ties to Tirole notes that end-to-end connectivity requires cooperation between competing firms like Netflix and Comcast, but adds that “if you leave firms to come up with the terms of the cooperation themselves, they are going to find a way to remove the competitive parts as well.”

Gans says Tirole solved that problem by employing “a set of rules and practices that would regulate interconnection terms among telecommunications companies for decades, while ensuring there were adequate incentives to compete — and not just on price — but on investment in infrastructure.”

His advice to U.S. regulators: “Open one of Tirole’s books … (and) it is time you listened.”

As for the consumer price problem, Gans says:

The issue in telecoms arises with what is termed the last-mile problem. You only have one set of cables or copper coming into your house. The solution adopted around the world has been to say, okay, one firm owns this cable, but what they have to do is provide access to these cables. So if I want another firm to provide me with TV or Internet, they have to allow that firm to effectively rent the cable from the other firm.”

That strategy worked well in the Netherlands, according to Ad Scheepbouwer, CEO of the Dutch telephone company KPN:

In hindsight, KPN made a mistake back in 1996. We were not too enthusiastic to be forced to allow competitors on our old wireline network. That turned out not to be very wise. If you allow all your competitors on your network, all services will run on your network, and that results in the lowest cost possible per service. Which in turn attracts more customers for those services, so your network grows much faster. An open network is not charity from us, in the long run it simply works best for everybody.”

But it failed in the U.S. Congress anticipated the same sort of infrastructure sharing when they passed the Telecommunication Act of 1996, but the incumbent operators were able to thwart that effort in courts, statehouses and local government.

This frustration was expressed by William Kennard who, as chairman of the United States Federal Communication from 1997-2001, was charged with implementing the Telecommunications Act. Near the end of his term he said “all too often companies work to change the regulations, instead of working to change the market,” and spoke of “regulatory capitalism” in which “companies invest in lawyers, lobbyists and politicians, instead of plant, people and customer service.” He went on to remark that regulation is “too often used as a shield, to protect the status quo from new competition, often in the form of smaller, hungrier competitors — and too infrequently as a sword — to cut a pathway for new competitors to compete by creating new networks and services.”

If regulators are not able to get ISPs to share their infrastructure, there is another alternative — government ownership of infrastructure. While the U.S. cable and telephone companies have fought vigorously against municipal networks, they have worked well in other places, like Stockholm, where the municipal government provides wholesale infrastructure and invites retail ISPs to compete. (It is noteworthy here that FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler says he wants to invalidate state laws prohibiting local governments from providing Internet connectivity.)

In a column on Tirole’s contributions, fellow economics laureate Paul Krugman says that Tirole recognized that there are no comprehensive theories of oligopoly and monopoly and:

Basically, [Tirole] made it OK to tell stories rather than proving theorems, and thereby made it possible to talk about and model issues that had been ruled out by the limits of perfect competition. It was, I can tell you from experience, profoundly liberating.”

My guess is that the executives at companies like Apple and Google were dealing in stories, like the ones described above, without reading Tirole. Thinking about and elaborating on the story had more to do with Apple’s iPhone pricing than the results of a game-theoretic model. It also sounds like economists like Paul Krugman, and also European regulators, are taking Gans’ advice. They are reading Tirole’s books. And so am I.

For aNewDomain, I’m Larry Press.

Based in Los Angeles, Larry Press is a founding senior editor covering tech here at aNewDomain.net. He’s also a professor of information systems at California State University at Dominguez Hills. Check his Google+ profile — he’s at +Larry Press — or email him at Larry@aNewDomain.net.