aNewDomain — Every academic term, as we talk on the subject of motivation, we get to Viktor Frankl and his objections to Jean Paul Sartre. Sartre asserts that our job in life is to accept the utter banality and the complete lack of meaning in life – and then to face up to that fact with courage.

— Every academic term, as we talk on the subject of motivation, we get to Viktor Frankl and his objections to Jean Paul Sartre. Sartre asserts that our job in life is to accept the utter banality and the complete lack of meaning in life – and then to face up to that fact with courage.

Frankl was a guy with every reason to believe that. His life during World War II was one of complete thrownness. Arbitrary choices of others dictated whether he lived or died, and under what conditions he lived.

This line: Left are the showers, right are the camps. The next line: Left is Dachau, right is Auschwitz. But the thing is, Frankl in the end rejected banality. And in one of the greatest works of 20th century psychology, Man’s Search for Meaning, he explained why: Because people who suffer for something can endure it, while people who suffer for nothing cannot.

So it takes about 15 minutes to get through this part of the unit. But today it took much longer. You see, I could not stop crying.

This never happened before, not on this topic.

I think it had something to do with this bit of news: Oskar Gröning, a former accountant at Auschwitz, admitted complicity in the operation of the death camps. He never personally did harm to anybody, but he knew what was happening there. He saw it every single day. He said nothing and did nothing.

I think it had something to do with this bit of news: Oskar Gröning, a former accountant at Auschwitz, admitted complicity in the operation of the death camps. He never personally did harm to anybody, but he knew what was happening there. He saw it every single day. He said nothing and did nothing.

In court, he appears to have considered himself beyond any Earthly forgiveness. He did not burden his accusers with such requests. And he stated that the crimes done there were beyond the judgement of men. Only God, he said, can judge such terrible sins.

Gröning was complicit in the deaths of 300,000 people. That’s an amazing number to contemplate. It is staggering, sickening.

And he received a four-year sentence.

The man today is 94-years-old. It’s conceivable he will serve out his sentence, but much more likely he will die in an infirmary long before those four years are done.The sentence is symbolic.

And as a symbol, it sucks.

Punishment is not effective for behavior modification. Science understands that, even if most actual people do not. At the same time, this sentence can be seen as the measure of the worth of a human life. More specifically, a Jewish life. Four years for 300,000 lives comes to this: 1/200 part of a day for each life taken.

In America, accessory to murder is punishable just as murder. In Germany, apparently, there is a different standard. If he is to serve part of a sentence, why not a hundred years per count, or three hundred million years confinement?

He’s going to serve just as much in any case, so why not give some more significant statement on the value of a life?

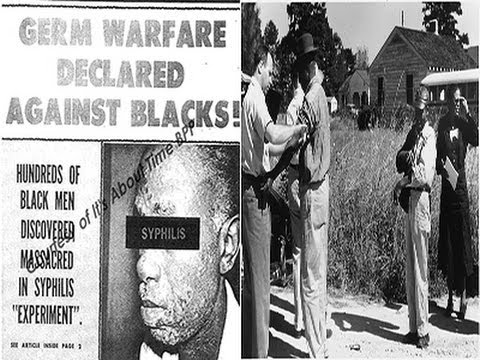

There’s that, and then there’s this: In the 1930s through the 1970s, we studied the effects of syphilis on human bodies.

In particular, we studied African American men with the disease and denied them treatment.

Even though treatment was readily available.

This was the shameful Tuskegee Experiment, which you can read about at this link.

The Tuskegee case comes up in ethics class at the graduate level. I try to get students to look at all the possible sides of each case, to see the good and the bad. Often they are scared to look at all sides, or they lack the imagination to do so. But it’s still completely necessary.

The reason is, the people who did this did not think they were doing something evil. They thought that they were contributing to the sum of human knowledge, aiding in the development of treatment protocols for the disease at hand.

We look at this case and see no ambiguity: The people in charge were clearly wrong, clearly evil, clearly at fault.

But it is precisely this lack of access to ambiguity that gets us into trouble.

We think we are good, and therefore that we cannot do evil things – or even morally ambiguous things. By refusing to think these situations through all the way, we fail to see how we are ourselves at risk for the same kinds of behaviors. Like racist behavior, sexually inappropriate behavior, dehumanizing behavior.

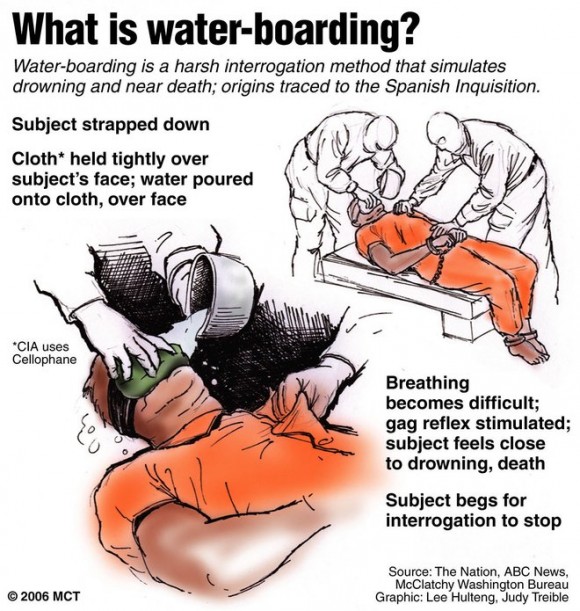

Psychologists who should have and did in fact know better took part in torture.

They developed programs of interrogation and enhanced interrogation, helped create the conditions in which maltreatment could occur and flourish, and covered up after the fact.

Other psychologists shielded those criminals from prosecution and ethics investigations.

Without a doubt, they all thought they were doing something good. And, believing that, they were incapable of examining the actual implications of their behavior.

We did this. Us. We repeated Tuskegee and we repeated Auschwitz. We dehumanized people so that we could mistreat them.

Nothing more is of any salience.

It does not matter what kind of people were tortured. They were people with civil rights and human ones.

Our job as psychologists is to protect those rights and defend their dignity.

Under duress or not, as psychologists we must be held to a higher standard than prison guards at Auschwitz.

So today I could not get through a lecture on Frankl and Sartre because I grieved the whole time.

I grieved those lost in the camps and those who presided over them, too. They were equally lost.

I grieved over those who sickened and died of syphilis in the Tuskegee experiment who need not have, and the doctors who allowed this to happen for the sake of knowledge.

And I grieved over terrorists, killers, and also innocent men who were tortured by or on behalf of Americans.

I grieved for us, that we have learned so little after so much suffering.

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

Image one of Auschwitz era Oskar Gröning: Independent.co.uk, All Rights Reserved; image two: Reuters.com, All Rights Reserved; image three: KatieBeaches.wordpress.com, All Rights Reserved.