aNewDomain — Hindsight is 20/20. Believing we knew what was going to happen all along, though, is pretty harmless. It’s believing others should have known that is the problem.

In 2012, Italy sentenced six seismologists to six years in prison. Their crime? Failing to predict a 2009 earthquake that struck the small Italian city of L’Aquila.

In the US, we scoffed at such obvious grandstanding. Obvious seismology is not mature enough to say just when and where an earthquake will strike. Public assurances of safety are perhaps out of line, as well as specific predictions of time and place – all seismologists can do is figure the odds.

Much of science is statistical in this manner. The meteorologist won’t even tell you there’s a 100 percent chance of snow when it is snowing right now. She will only say the last 100 times we saw these conditions, there was snow 43 times, so we’re saying there’s a 43 percent chance of snow today.

Now Italy wants to lock up her scientists for getting it wrong.

We scoff at her justice system, maybe, but reckon nothing like that would ever happen here. And it’s Italy’s business if she wants to guarantee nobody feels comfortable practicing science within her borders. Seismology in particular might be set back decades as scientists refuse to make predictions for fear of prosecution.

The information they need to predict earthquakes and protect public safety will be longer in coming because a judge doesn’t understand the nature of science.

Closer to home, we have a problem with mass shootings. Every time one happens we rehash the shooter’s mental state, politics and gun laws.

Closer to home, we have a problem with mass shootings. Every time one happens we rehash the shooter’s mental state, politics and gun laws.

Most chilling for me, though, is that now we have started to check on the disposition of their psychiatrists.

If tectonic pressure release is unpredictable, human behavior is more so to the millionth degree. Humans are at best hopelessly chaotic systems. We can say nothing of the immediate behavior of one individual, only make predictions of broad swaths of humanity based on statistical evidence, when such evidence is available.

When I present to my classes that unemployment is the number one prediction of crime, there is always this instant objection: Doesn’t the person make a choice?

Someone will say something like: Well, my grandmother’s second cousin’s brother’s son was unemployed, and he never did any crimes.

Well, yes, thanks for the anecdotal evidence (a story that appears to contradict the statistics but is unverifiable and not representative of the data). And yes, for one given individual there is a factor of agency to consider.

But in the broad statistical sweep, it is clear that more people make the individual choice to be responsible for crimes when they are poor, unemployed, live in disadvantaged neighborhoods, and generally lack the opportunities shared by more fortunate folks.

So confronted with an out of work man, I can say absolutely nothing about his likelihood of committing a criminal offense. I can say people in general behave thusly under these conditions, but one person is utterly unpredictable.

Periodically, psychiatrists and even psychotherapists are sued by the families of patients who succeed at suicide attempts. Following the Aurora theater shooting, at least one family member sued the shooter’s psychiatrist.

And we hear about state lawmakers drafting bills to make it easier to hold medical and psychological professionals accountable for the actions of their patients and clients.

To a great degree, though, we’re even worse at predicting the actions of our customers than are seismologists or meteorologists at predicting natural processes.

To a great degree, though, we’re even worse at predicting the actions of our customers than are seismologists or meteorologists at predicting natural processes.

This has to do with the aforementioned dizzying complexity of human beings. It also has to do with the nature of our work.

For our patients and clients to get better, we have to trust them. The job of the therapist in particular is to identify with the subjective experiences of the client, to believe they are being as truthful as they can. When they say they feel better, the more we trust that, the better chance they have of getting well.

This could be why maybe half of psychiatrists lose patients to suicide – although that half of the business is less about relationships and trust these days than about administering medications. Still, what are we to do – sue half of all psychiatrists for medical malpractice for trusting their patients when the psychiatrist asks them about suicide ideation and the patient denies it?

Predicting human behavior is somewhere between nearly impossible and actually impossible. It is a problem that plagues parole boards, licensing boards, clergy admissions proceedings, airline pilot recruiters, police academies, covert service hiring and training, a million other places and occupations. How can we let people out of prison when they have been violent in the past – how can we decide they won’t be violent again in the future? How can we let people into sensitive, high-pressure or high-trust occupations?

Protecting the public is a good thing. Placing the guilt for an individual’s suicide or homicide anywhere but with that individual, though, opens us all up to a lot of risk. A risk of spurious lawsuits, to be sure, but also a risk of making it impossible to practice helping professions.

Italy won’t get any warning of its next earthquake.

How long will mental health professionals continue to practice in states that make them responsible for perfect prediction of the unpredictable?

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

Northern Italy 2012 earthquake cover image: “Drinks Shop – Finale Emilia – 2012 Northern Italy earthquake” by Mario Fornasari from Ferrara, Italy – Nel negozio. Licensed under CC BY 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Bullet impact image: “2010 0517 Soi Ngam Duphli 01” by Takeaway – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

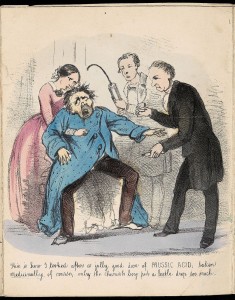

Therapy painting, image: See page for author [CC BY 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons