aNewDomain — I read an interesting article today about children growing up godless. It’s just an opinion piece but it is well cited. In it, Phil Zuckerman contends that secular families might in some ways be more moral than religious ones.

“Moral,” of course, is a loaded term. It is difficult to discuss morality objectively. And it is hard to operationalize the term in a way that both religious and unaffiliated people would agree with. I would suggest that racism is pretty unambiguously immoral, however. Some researchers have even found a correlation between religion and racism.

In other words, more secular people are less racist. Also, they are demonstrably less sexist, heterosexist, anti-immigrant, authoritarian and more rational.

Why it is more moral to be more rational

Okay, that last one is tricky. Why would it be more moral to be more rational? The field of ethics sheds some light on the problem — especially the new approaches to ethics that modern classrooms are having to embrace.

The last version of the American Psychological Association’s (APA) code of ethics made some really substantive changes in the way we approach our professional ethics as psychologists. We moved away from a “Thou shalt not” approach, a set of commandments, and toward an empathy, beneficence and compassion-based model. Rather than banning us from accepting gifts from clients, for example, the APA now encourages us psychologists to think deeply about the cultural significance of such gifts, their impact on the therapeutic relationship, client finances and so on.

In the “Thou shalt not” model, therapists were rejecting trivial gifts from clients that were important. The gifts had cultural significance and a rejection of them potentially harmed the therapeutic relationship and possibly the client. In that model, dual relationships were strictly prohibited — making life extremely difficult for therapists practicing in small communities where it is impossible to never cross paths with one’s clients.

The modern code encourages thoughtfulness, consideration, based around the principles of beneficence and non-malfeasance. Now we must ask ourselves: Is this action going to result in the most good and the least harm for the client?

Some things in the new APA ethics policy are still strictly prohibited. For example, having sex with clients remains unethical, illegal and pretty detestable.

In the ethics class I teach, though, I challenge students to think this through all the way. Strict prohibition is not working. People shalt even though the laws and codes say shalt not. This remains an endemic problem for doctors, psychologists and psychiatrists. What we are not doing is encouraging people to think through the consequences of their actions. Is sex with this person in their best interest – the most helpful, least harmful thing we can do? And, as David Elkins points out in his Humanistic Psychology: a Clinical Manifesto (2009), these rules often are arbitrary and sometimes contradictory. For example, the ethics codes seem to allow us to have sex with former clients once two years have elapsed since the last treatment — but one never, ever should be friends with them.

Religious thinking is set up to to try to solve these kinds of problems, but it often fails. Strict rules handed down by God, inviolable, which in turn lead to blanket applications of those rules in ways that are thoughtless, irrational, harmful – and immoral.

The trouble with not questioning authority

For some people, obedience to authority is moral. This tends to be a conservative viewpoint. The trouble is that authority can lead us astray. Following the Vietnam war, for example, our armed forces started to spend a certain amount of time and effort educating soldiers on when to refuse an unlawful order. I remember some pretty good talks about this in Basic Military Training when I was a recruit in the 1990s. These efforts came in response to the massacres and murders soldiers carried out under orders and made public back at home.

The trouble with an unquestionable authority is that, when the orders seem not to make any sense, we are left to rationalize them ourselves. The ongoing fight for civil rights for people of color is a prime example; we are racist today mostly on inertia. The newer civil rights arena, same-sex marriage, is entirely a religious versus secular battle. Even the Supreme Court, one of the more conservative in history, agrees that essentially nobody is harmed when gay people marry and therefore nobody has legal standing to oppose the practice. But same-sex marriage does undermine the rules and order delineated in religious texts.

With these texts, we lack the ability or even the will to ask the questions the way a professional ethicist might. Through tax rates, inheritance penalties, child custody and a million other potential attacks, same-sex marriage materially harms same-sex couples and benefits nobody. Not even a single hetero marriage has ever been materially improved by denying same-sex couples the same rights as everyone else.

I would even argue that denying same-sex marriage harms all of us, in the same way racism harms all of us. My rights are threatened when they are provisional, and in these cases my rights are provisional on my being White and heterosexual. In some places they are also dependent on my faith — if I have to be judged in a court that displays the Ten Commandments in the courtroom, for example, or I have to eat prison food that is not kosher or halal. In other words, none of us is free until all of us are free.

For some folks this is all a problem. It’s called “moral relativism,” the idea that morality is not best expressed in absolute terms. But it’s important to try to accommodate as many systems of moral thinking as we can. That is called freedom and respect for diversity.

Scientifically speaking, ethics pioneer Lawrence Kohlberg outlined the development of human morality in a hierarchical system. At the lowest, least mature end of the scale, we have obedience to authority through promise of reward or threat of punishment. At the top end, post-conventional morality, the person carefully considers all the angles and acts on an internalized set of principles rather than the guidance or rules or laws.

Criticism came quickly that a hierarchical model is a masculine model and one that crushes diversity, valuing some kinds of moral thinking over others. How can we call one way of moral thinking “better” than another, and make it superordinate in a hierarchy? Again, morality is a loaded term and difficult to operationalize or even really define. In the United States, though, the constitution was written by people who seemed to believe that the most freedom for the most people, avoiding authority (tyranny), and encouraging the best education, would result in the most moral outcomes for her people.

If the most liberty means everyone has the same rights independent of their skin color or sexual orientation or religion, and if the data are correctly represented, then moral relativism is indeed more moral than moral absolutism. As the country grow less religious, we become more moral — not because God is bad or evil or because religion is small-minded, but because, without recourse to absolutes, we are forced to be more thoughtful.

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

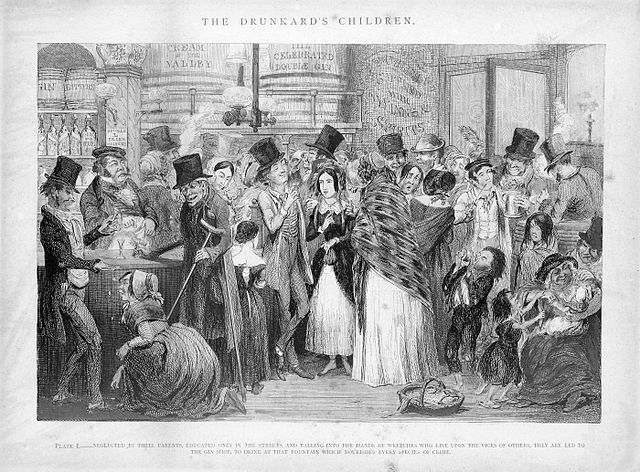

Cover image: “Cruikshank; The drunkard’s children Wellcome L0007439” by Wellcome Library, London – http://wellcomeimages.org/indexplus/obf_images/bb/85/d8a8317c0d9125b66f7136708bf4.jpgGallery: http://wellcomeimages.org/indexplus/image/L0007439.html. Licensed under CC BY 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons.