aNewDomain  — The fundamental question of psychology, at least according to the first chapter of just about every psychology textbook, is this:

— The fundamental question of psychology, at least according to the first chapter of just about every psychology textbook, is this:

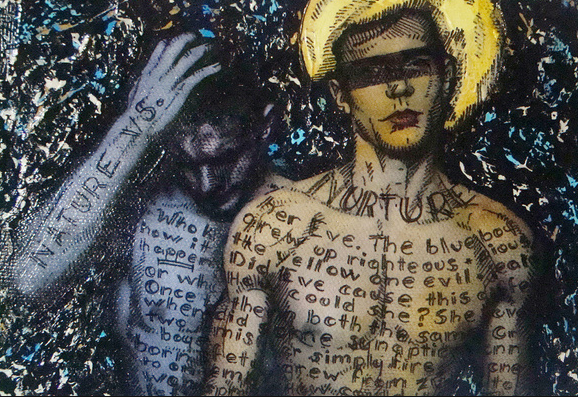

Are people who they are, more because of their biology (nature) or their family and social circumstances (nurture)?

In other words, what’s more influential: nature or nurture.

Unfortunately, the nature vs. nurture debate is crap.

Now, there is a central question in psychology: Is psychology going to be a profession? And, if psychology is to be a profession, who will control it?

Nature vs. nurture, you see, is a question outside of psychology. It kind of hangs out in the textbooks out of inertia because textbooks are mostly approved by people who do not understand the issues. But this particular question is, for a psychologist, largely invalid on its face. Because we’re psychologists.

What good is a psychologist at all if the fundamental answers to all our questions about people come down to their genes, neurotransmitters, brain lobes?

Our level of intervention is psychological – most obviously in the counseling and psychotherapeutic parts of the discipline.

We chose up sides a long time ago, you see.

Of course biology sets constraints. But if you cannot help someone change through interaction with them, what’s the point of doing psychology at all?

That is the point. And that might be another factor behind asking the question in every textbook as though it was ever a major issue for us.

Who will control psychology?

In the early days, psychology was part of medicine. Psychiatry still is – and look what they’ve done with that. The American Psychiatric Association is just about a wholly-owned subsidiary of psychopharmacology these days with few if any psychiatrists even attempting any interventions other than prescription ones.

Early psychologists had to struggle to create a licensing process, a professional code of ethics, an instructional and practical program separate from psychiatry. At the time they fought hardest against psychoanalysis, a division controlled at the time entirely by psychiatry. Breaking away from psychoanalysis was seen as a mutiny, serious damage to the empire. When behaviorism came along, it created another major rift. Humanistic and behavioral psychologies duked it out for decades, on opposite sides of an argument over free will.

But they mostly agreed, and still do, that humans are in nearly every significant way limited by their biology but heavily influenced by their environments. Even psychoanalysis at the time, while perhaps pessimistic about the possibility of long-term change, agreed on this. We just wrangled about the how.

And the who.

Who gets to control the profession? To whom do we pay our licensing dues?

The thing about the nature/nurture debate is kind of like the stickers conservatives make us put in biology textbooks about evolution being a theory to be considered critically. Of course you should consider everything critically. But the question here isn’t really a question.

Modern medicine has chosen up the other side. NIMH bit the same bullet, doubling-down on the assertion that neurotransmitter levels and so on are at the heart of mental illnesses. In some states, psychologists campaign to be allowed to prescribe psychotropic medications. All three of these stances benefit our for-profit pharmacological system.

If you want to do neurology, more power to you. That’s a worthy field of study and it is possible to help people from that stance. Things like Alzheimer’s disease aren’t going to be solved through good relationships and talk therapies; they’re going to be solved by medical professionals with neurological expertise. But as a psychologist, as a therapist, these perspectives just aren’t of any use.

People do get better through therapy. Mounds of data support this assertion now. And that was never a question. Keeping psychology part of medicine, though, funded through medical insurance, regulated through the psychiatric publication we use to code mental illnesses, is highly questionable.

The main evidence for problems of living as neurotransmitter deficits comes from the people making neurotransmitter drugs.

And, for a therapist, when a client explains their problems of living, you don’t get your microscope and a scalpel.

You talk to them. Love them well. Help them access agency, not quash it with talk of biological determinism.

Responsibility can be scary, especially if you can’t tell it from fault.

And I think we can still take responsibility for how we teach beginners in the field.

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

Cover image: Amelia Wilson, for Health, Culture and Society, All Rights Reserved