aNewDomain — At the beginning: Sartre suggests that there is no inherent meaning in life. Things happen for no reason, with no rationale or grand plan. People of course find order in events and comfort in that order; the idea of a meaningless universe is terrifying to us.

According to Sartre, if we have a job here on Earth, it is to accept meaninglessness and live with it bravely.

According to Sartre, if we have a job here on Earth, it is to accept meaninglessness and live with it bravely.

In other words, recourse to meaning is cowardice.

Or is it?

Viktor Frankl, generally accepted as an existential psychologist although he was a psychiatrist and called his own practice logotherapy, had a different opinion.

Despair, he suggested, equals suffering without meaning. He accepted generally there is no inherent meaning in events, but also that people have a need for it and that need is not cowardice at all.

In fact, it can be courageous to find meaning in the most desperate of places.

He knew what he was about. Frankl survived the camps in World War II. He chose not to flee the country even though he had permission to leave; his elderly Jewish parents needed his care. When the Nazis came for him, one of the first things they did was to burn his manuscript on logotherapy in order to debase, dehumanize him, return him to the state of animal they thought fitting for a Jew under the Third Reich.

On the way to the camps, he faced the Sartrean reality over and over again. He went with the soldiers because they said so; there was no inherent meaning in their authority. He was sent to one train rather than another, and so he lived. He was sent through one line rather than the other. His line went to the camps, the second line to the mass murder facility. Only the condition of his birth — maleness — saved him from gassing.

Over and over again, an arbitrary decision by a man in uniform saved his life but sent him into further suffering.

Interview with Dr. Viktor Frankl video: Yecto YouTube channel

There was no inherent meaning in any of this. No grand order set forth by a benevolent God. Just the whims of young men with authority loaded and chambered and carried in a spare hand.

Frankl didn’t give in to the Sartrean reality. He worked. Brutal work with little food, no medicine, nothing of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs fulfilled except that top tier: self actualization.

He observed that there were essentially two kinds of inmates. Some could think of the future: imagine their wives and children alive, or brothers or sisters, imagine going home. Having a career or at least a job. The others imagined no future, lived only for the next moment.

Despair equals suffering minus meaning

The latter group succumbed to despair. There was no meaning in their suffering: nothing to live for, no reason to wake up to more suffering tomorrow, no hope of an end other than death. These are the ones who gave up, climbed the hill the Nazis seemed to keep for this purpose, and jumped to a fatal end below.

Frankl had a meaning. He had his book, the story of logotherapy. It was just ashes in a waste tip now, except that it also lived in his head and lived in his observations. He imagined himself one day visiting America to lecture college students on the meaning of meaning, the use of logos to help distress.

He survived to enact this destiny.

Meaning can mean a lot of things. In Zen tradition, meaning is found in banality, not in spite of banality. The highest expression of enlightenment is to be ordinary, do ordinary things: sweep the floor, build your cooking fire, trim the hedgerow. The difference between the enlightened and the mundane is one does these tasks awake, with joy in all the small miracles of existence, while the other does them asleep.

Meaning can be fulfillment. Relationships that consume you, work that sets you afire, a life lived well.

Frankl knew these things, although he wrote too often and excitedly of finding an explicit meaning for someone, handing it to them, pronouncing them cured.

Everything happens for a reason? Really?

Here is the banality: everything happens for a reason. A well-intentioned platitude that leads us away from truth. Sometimes the truth is that grief matters, that trauma matters, that violation matters. “Everything happens for a reason” is an undue invitation to cheer up, get over it, move on, let it lie. Look to the future.

But there might be a bigger meaning in our grief. For example, grief informs us of our values. And grieving publicly, socially, helps us to achieve a new relationship with the dead — internalize their most important qualities, remember them in our actions and feelings and not only in stories. Death didn’t happen for a reason; it’s just that we are beings of a middle scale. Not gods or angels, not worms or feces. Not galactically huge, engulfing light-speed distances. Not microscopically tiny. Neither completely ephemeral nor eternal. Middling beings that come into being, do the best we can, and then die one day according to no special plan.

But there might be a bigger meaning in our grief. For example, grief informs us of our values. And grieving publicly, socially, helps us to achieve a new relationship with the dead — internalize their most important qualities, remember them in our actions and feelings and not only in stories. Death didn’t happen for a reason; it’s just that we are beings of a middle scale. Not gods or angels, not worms or feces. Not galactically huge, engulfing light-speed distances. Not microscopically tiny. Neither completely ephemeral nor eternal. Middling beings that come into being, do the best we can, and then die one day according to no special plan.

We are in deadly danger of taking too firm a position on this. Our get-over-it culture that values only optimism, youth and good looks represses too much of our guilt and grief in meaning-telling and conversely offers us too little time and space for meaning-making. Grieve in a way other people are distressed by and you might find yourself medicated for depression, unable to feel the anguish that informs you. Short of that, people will assail you with their platitudes around death and grief and loss. Drive you to feel your feelings are inappropriate. That your faith is too weak when you feel sadness. After all, if your loved one is with God now, how can you grieve them? Your tears seem a contradiction of the comforting story.

Life is no good without some trauma. On average, people need about three traumatic events in their lives in order to feel satisfied with their time on Earth by age 65. A weird finding, alluded to by the Mighty Mighty Bosstones:

I’m not a coward, I’ve just never been tested. I’d like to think that if I was I would pass. Look at the tested and think there but for the grace go I. I’m not a coward, I’m afraid I might find out.”

We need to be tested. We need to try ourselves against life, to discover in ourselves the courage, empathy, compassion, mettle, determination to carry on. To learn that grief is vital but not final. That truth and courage are in the event and in the rituals of burial and in the isolation of grief, and also on the other side of it – when we have grieved enough to make sense of the grief.

Perhaps everything does happen for a reason. I can’t prove otherwise, after all. But perhaps it is best to leave that reason be, not force it. Because the meaning is in the journey and there are no shortcuts.

I No Longer Seek It

A student asked his master, “What happens to a person after death?”

The master studied the student for a time until the student thought he was meant to learn from the silence of the master. But then the master spoke:

“Go out of this place and walk on the north road. Go through the towns and villages you find there, go through the forests that exclude the villages, go into the mountains. There you will find a bridge that has fallen. Walk across that bridge and you will know that which you seek.”

The student packed a meager bag and set out that day. He walked through the villages he found, eschewing succor or companionship from the people there. He walked through the forests where no person could live, refusing the bounty of the trees and roots he found there. Many days later, he came to that bridge in the mountains and stood looking down into a dark chasm, wintery waters rushing past far beneath his feet.

Some time later the master found the student in the village outside the monastery, consorting with the villagers and eating what they offered.

“Did you discover what happens to a person after death?” asked the master.

“I no longer seek it,” replied the student.

I No Longer Seek It: Excerpted from Paintings in Sand by Jason Dias, 2010.

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

Shanghai Garden cover image and image above: By Carsten Ullrich from Shanghai, China (2218 Yangshupu Lu, ShanghaiUploaded by Fæ) [CC BY-SA 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons

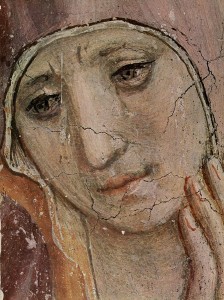

Fra Angelico image: “Fra Angelico 053” by Fra Angelico (circa 1395–1455) – The Yorck Project: 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei. DVD-ROM, 2002. ISBN3936122202. Distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH.. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.