aNewDomain — Viktor Frankl tells us that despair is suffering without meaning. The equation is D=S-M. Seeing those three letters together reminds me of the DSM, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Illness that psychologists use to tell you what you’re suffering from.

What are you suffering from? That’s something we’ll circle back over the next few hundred words.

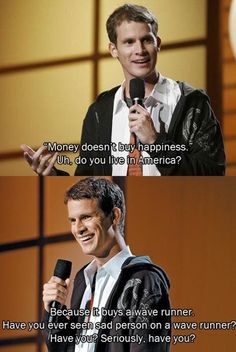

But first, watch this:

Frankl is in good company making the assertion that despair equals suffering without meaning. On this, he’s with Friedrich Nietzsche: A man with a Why can tolerate almost any How. He’s with Martin Luther King Jr., too: Unearned suffering is redemptive.

And he’s with Irving Yalom who, aware of all these others, said that we should certainly not seek out suffering for its own sake but, when presented with unavoidable suffering, we ought to consider whether that suffering has within it any potential for our growth and learning.

We cannot, of course, reduce all of Viktor Frankl’s legacy to just this one equation. Frankl’s work on logotherapy makes it clear that meaning is at the heart of life — that life minus meaning equals despair.

That is, suffering itself can be a product of meaninglessness.

Meanings need not always be overt.

Experimental evidence demonstrates that looking at a picture of loved ones helps us tolerate pain. The pain is inflicted as part of an experiment; we are not enduring the pain specifically for love of family or romance, though.

But love — connectedness — is intimately a part of meaning and meaning-making for humans. In other words, relationships might mean inherently nothing and yet do seem to provide sufficient reason (or meaning) for living.

What I wonder, though, is whether despair might be present without any suffering at all, so long as meaning is absent.

Imagine, for example, someone born into wealth.

Such a person is protected at all times from the concepts of time and aging, surrounded only with beautiful young attendants.

He is provided with only the best of foods, education that leaves out our history of violence, like war, rape, dispossession, invasion and poverty, and dwells on our freedom. That person is protected from illness, from injury.

And he is always kept safe. His attendants change day by day so they can never experience attachments and therefore never loss. His sexual encounters are unstressful. They are only casual and always gratifying.

Would that person arrive at adulthood happy?

Behind that happiness, might there be any sense that something is missing?

In the Little Buddha story, Buddha’s origin movie, exactly this setup occurs. But he discovers the real world by accident: he wants to go outside the palace walls, to see the people. His father poo-poohs the idea but, when Siddhartha will not relent, has all the old and infirm and poor people hidden, has Siddhartha paraded along a route carefully selected for its inoffensiveness.

But he accidentally sees an old person.

That sight makes him question everything and puts his feet on the path towards ending suffering.

It’s a nice story. But I tend to think suffering is necessary and human but I can’t argue with any person who wants to stop doing it.

I’ve suffered enough in my life to empathize.

But the question, really, is this: What makes Siddhartha want to go outside the palace walls in the first place?

Is it some feeling, some itch, some under-the-radar knowledge that life cannot possibly be so good? Or is it that such a life is devoid of any meaning?

At the very least it is empty. Every wish is granted, every pleasure is available, and there is nobody around to tell you no.

There’s a Twilight Zone episode, from the original series, called “A Nice Place to Visit.” In it, a hustler dies, wakes up in the afterlife.

In this version of death, he makes every shot on the pool table. He wins every dice throw and every coin toss. The booze is free and the babes always say yes.

An angel comes to check in with him. To the angel, he says “I don’t mean to seem ungrateful, but I’ve been here a few days and this is already boring.

“There’s no challenge, no fun in winning all the time with no effort. I’m bored. It is not my idea of Heaven.”

To which the angel replies, “Who said this was Heaven?”

How many of us seem to have everything — a big-ass TV, a house with nine rooms, an RV outside, and a fridge packed with indulgences — yet still we sense something is missing?

We go to our jobs anxious. We might get fired. Performance reviews are coming up. There’s a boss, there are also some people you barely like.

And you can’t shake the sense there’s something more fundamental wrong here – you spend your day selling people things they don’t need or even really want and you can’t quite square that with your conscience. Or you’re there in the room with your family but nobody has time for anyone else. The smartphone never stops talking to us.

And everyone else’s lives look way better than ours on Fakesbook.

We go to sleep anxious. We eat pills to get to sleep and then drink a six dollar cup of coffee on the way to work to shake off the fatigue.

But it isn’t fatigue. Not really. It’s despair you’re too happy to notice.

Something is missing, all right. What’s missing is meaning.

I mean, what the fuck is this all for?

Maybe you go to church on Sunday morning and you feel better for a while. But you don’t live any of your values, not really, so at night it’s still too many beers or a couple of Lunestra tablets or maybe both to stop that nagging feeling that everything isn’t okay, even though that is strange to say because it couldn’t be more perfect.

A life minus meaning. What does that equal?

What it equals is pointless suffering.

But what about pointless happiness?

Our solution to our problems of angst and anxiety is increasingly psychopharmacological.

We go to the doctor, who gives us pills. We get Xanax and Celexa.

And we get Ambien, Seroquel, Ritalin. We get whole great fucking fistfuls of pills to choke down.

Does that help?

And what if it did?

In other words, what good is happiness that comes out of a pill bottle? Isn’t that ultimately meaningless, too? This is not happiness that comes as a result of relatedness, of striving for something and succeeding or of taking a moral stand win or lose.

It’s an artificial mood adjustment.

Would you smile at a funeral? Laugh through a natural disaster? Meet others’ suffering with gladness?

Then why be happy in a banal, meaningless existence in which your most important concern in life is whether people can marry each other or if women are allowed in the new Ghostbusters movie?

We aren’t happy. We’re not even content.

We’re overfed and undernourished, entertained and disengaged.

We are hydrating and exercising to stay ‘fit’ for a long, pointless life.

Every psychology overtly or covertly espouses a “good life.” Psychoanalysis suggests a more conscious life is a better life. Behaviorism tells us a conforming life is best. Cognitive behaviorism wants us to be free of symptoms. Positive psychology wants us to have the right ratio of good to bad feelings.

The good life as proposed by the DSM is one well in line with behaviorism, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and the tenets of Positive Psychology.

A symptom-free life, well regulated and conforming, without too many bad feelings and only just enough good ones.

But maybe your feelings aren’t symptoms at all.

Maybe your feelings only reflect your inner Siddhartha wondering what might be outside the palace walls.

I doubt you live in a palace at all, actually, but you wonder instead what’s outside of a life of barely making your mortgage and car payments and credit card tabs. Of you wonder where the next meal is coming from, or you wonder why your expenses always increase to exceed your income.

I can’t tell you. No one can.

But you know where to start.

The truth lies off the path of the guided tour, in some unpleasant truths behind the bazaar.

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

Image one of Viktor Frankl: BrainPickings.org, All Rights Reserved; image two: Pinterest.com, All Rights Reserved; image three: “Little Buddha imp” licensed under Fair use via Wikipedia; Image four: TwilightZoneVortex.Blogspot.com, All Rights Reserved; image five: Gizmodo.com, All Rights Reserved.