aNewDomain — U.S. currency looks pretty boring compared to other currencies. Its somber color scheme and stern political images distinguish it. But don’t expect the look of U.S. money to get snazzier anytime soon. There’s so much subtle symbolism going on that our money is unlikely to change much for a long time.

Adding the first woman to U.S. banknotes and excising the Stars and Bars of the Confederate Battle Flag from public life 150 years after the end of slavery are hot news stories, sure. But both developments are so late in coming. American symbolism is pretty stodgy and ingrained.

That said, as the saying goes, Where one’s treasure lies, so lies one’s heart. America’s treasure lies in worldly goods, and U.S. bills deeply reflect that. Here’s what else the symbolism and colors on currency tell us about ourselves, our allies and our enemies.

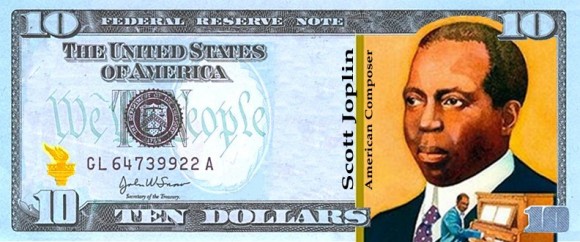

If American currency followed the pattern set by democratic countries like Canada, the UK, Denmark and Sweden, we’d have colorful banknotes bearing cultural images like this $10 Scott Joplin note:

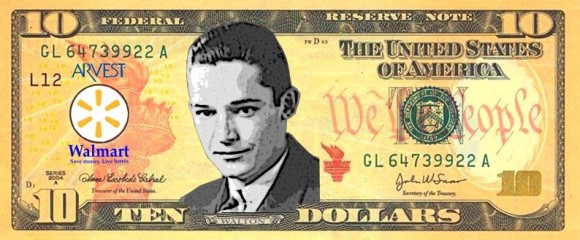

But American currency like this isn’t likely to happen any time soon for the reasons I explain below. What we’re more likely to get if we decide to change is corporate-sponsored currency that depicts beloved industrialists like this $10 Sam Walton note, endorsed in this specimen by both Walmart and the Walton family’s Arvest bank:

Why does U.S. money look so boring?

Among democratic countries, American currency stands out not only for its narrow palette of green but also for its ultra-authoritarian images of political figures. Compare the stern image of Lincoln (an elected president) on the $5 bill with the somewhat bemused expression of the Queen (a hereditary monarch) from the £20 pound note:

The Lincoln depicted on the $5 bill doesn’t look like the guy who would quip, “Better to remain silent and be thought a fool than to speak out and remove all doubt.”

The Queen looks merciful. Lincoln, ironically, does not.

But would you risk the economy for creativity?

Some of the seriousness of U.S. currency has an obvious explanation: The U.S. dollar is the world’s dominant currency. Not only is the U.S. the world’s largest economy, but the U.S. dollar is the official currency of eight countries besides the U.S., and it is the unofficial currency of 15 other countries.

Some of the seriousness of U.S. currency has an obvious explanation: The U.S. dollar is the world’s dominant currency. Not only is the U.S. the world’s largest economy, but the U.S. dollar is the official currency of eight countries besides the U.S., and it is the unofficial currency of 15 other countries.

Would you believe that more than half of all U.S. banknotes in circulation are held outside the United States? That’s part of what they mean by the term “reserve currency,” of course. U.S. banks also hold vast amounts of money in reserve as “reserve currency.”

And like it or not, U.S. money concerns lots of folks outside the U.S.

To sustain world confidence in its currency, U.S. banknotes include a number of features that the public can use to readily judge the currency’s authenticity and seriousness.

In other words: Don’t hold your breath for the Mickey Mouse dollar (shown above) or the Elmer Fudd $20 note. Cute ideas. Not practical for American shores, though.

And anyway, were America to issue some kind of dorky or funny currency, the U.S. economy would be the butt of that joke, and it wouldn’t be pretty.

Symbolism. It matters more than you think.

But how much does the symbolism in currency images really matter?

The answer depends on the image.

Every country’s currency amounts to a product of sorts that says something about the country that produced it. Currency, particularly a banknote, provides one means for branding a country.

The design of a currency tells us a lot about the country that produced the currency if we look closely enough. Currency can even change the tone and timbre of a dialogue both within the country and without.

This makes sense intuitively, doesn’t it? We see our money at every cash transaction. We see the images often. Surely they seep into our collective consciousness.

And think about this: U.S. currency has not substantially changed within the lifetime of any living American. That’s a lot of repetition of the same set of images over and over for the course of more than a few generations. You know those old commercial jingles from your childhood that you still remember? Same idea.

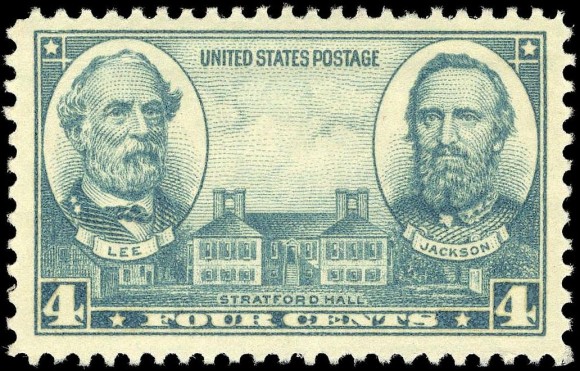

Luckily, Stonewall Jackson will never be allowed.

Of course, some images just won’t do on U.S. currency anymore.

Although Confederate Generals Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee were honored on a U.S. postage stamp in 1936 — and again in a somewhat veiled form as late as 1970 — it’s highly unlikely that the U.S. government will ever again honor a Confederate general on a postage stamp, much less on our all-important paper currency.

Today, we understand both men as treasonous racists. They also played for the losing side in the U.S. Civil War. Why let losers adorn our money? Won’t happen.

In case you’re curious, here’s that stamp I told you about:

Can you imagine the worldwide impact of a Stonewall Jackson $50 bill, though? The simple act of honoring a racist general would be incredibly costly to the U.S. economy — so costly that I suspect that even the most conservative U.S. presidential candidate you could think of would never be so nearsighted as to even ponder such a thing.

Harvey Milk will never see a buck, either.

What about the prospects for images of U.S. progressives on federal banknotes?

Unlikely. While such images would strengthen America’s worldwide brand, the domestic political consequences of such a move would be huge. It’s one thing to have a Shirley Chisholm stamp and a Harvey Milk stamp. They’ll never make it to U.S. paper currency.

It is true, though, that democratic countries often place images of influential artists and scientists on their currencies. Such countries also often refrain from including political images on their currency, apart from the inclusion of hereditary monarchs like, say, the Queen of England.

Could this seemingly mild step ever happen for U.S. banknotes? Well, let’s consider.

You will see such figures on the currency of most other democratic countries. There are images of Adam Smith and Charles Darwin on British currency, and Jane Austen is soon to join the mix. Danish money depicts Danish composer Carl Nielsen and Danish physicist Niels Bohr. And Swedish currency depicts scientist Carl von Linné, engineer Erik Dahlbergh, and author Selma Lagerlöff, who was the first woman in the world to win the Nobel Prize in Literature:

The reverse of the Lagerlöff note depicts one of her characters, Nils Holgersson, flying on the back of a goose over the Swedish countryside.

Now ask yourself: Do these cultural images make British, Danish and Swedish currencies weaker?

Clearly they don’t. The pound sterling until recently was the world’s third most held reserve currency. The Danish and Swedish economies on a per-capita basis equal or exceed the U.S. economy.

The point is, there’s no compelling economic reason for adorning U.S. currency with only the grim images of political figures.

Maybe Scott Joplin has a chance …

Consider the chances for a Scott Joplin $10 bill and its political impact.

Joplin’s ragtime style and compositions were extraordinarily influential in American music. They were game-changing. Joplin rejuvenated American popular music and created an appreciation for African American music among all Americans, regardless of race and across musical genres. Joplin’s syncopation and rhythmic drive drove out the stuffy Victorian-influenced music that preceded him. And he created all this without creating any controversy. Sounds like an American hero worthy of at least a $10 bill, no?

The nation has previously honored Joplin with a postage stamp, but would it ever depict him on currency? Nope. The whole country would have to change for that to happen for reasons I’ll get into in a second.

Not really. Joplin has no chance. Here’s why.

U.S. currency depicts only authoritarian political figures. In this, we have parted company with most other democratic countries in the world. We are more similar in our preference for stern politicians to states like Iran, Saudi Arabia, North Korea, Moldova and Malaysia.

It is no accident, then, that the U.S. rate of prisoner execution and incarceration is more similar to such totalitarian states than to that of our European allies.

Currency not only reflects a country’s political identity. It also reinforces it. We see ourselves as stern and tough, and we see our government at the center of it all.

OTOH, the Nazis were tough but their money was soft.

Like kings and queens, dictators love to adorn their currencies with their own images. Yet Adolf Hitler, for a time the most successful and ferocious dictator going, chose not to do this. Rather, he confined his image to postage stamps:

Nazi-era German money mostly depicted vague symbols of German ideals (like wholesome German country maidens) or German personalities who’d achieved success in humanities, the sciences and so on.

Notice that the 100 reichsmark note (below) contains a swastika, but the image on the note portrays famed German chemist Justus von Liebig:

Liebig is inarguably the founder of organic chemistry and made important contributions to the agricultural sciences, which included work that led to the creation of popular British food spread, Marmite. He also was a fairly liberal scientist who didn’t have much to do with the Nazis, aside from having a grandson who belonged to Nazi Germany’s anti-Semitic Pan-German League.

The senior Liebig was far more interested in the “nutritional value of meat juices.”

Perhaps the Nazi regime was going for a far more subtle message in their selection of Liebig, one that did resonate well among Germans at the time. The use of innocuous figures and messages on everyday Nazi-era currency belied the truth of the totalitarian state Hitler and his cronies assembled. I can imagine someone arguing that Hitler was “modest” because his picture only adorned stamps — unlike the former Kaiser — but that probably was just clever PR.

And Harriet Tubman? Her prospects look awful.

Looking forward, U.S. currency is far more likely to be adorned with the face of a genocidal maniac like Andrew Jackson than a cultural hero like Harriet Tubman. Tubman isn’t likely to replace even a moderate capitalist and wannabe abolitionist like Alexander Hamilton. This is because many conservative eyes look at Tubman as less a cultural figure than a polarizing political one.

For the same reason, U.S. currency is unlikely to depict Frederick Douglass any time soon, even though Douglass has been dead for going on 120 years now.

It’s hard to imagine an accomplished American of any stripe who is free from conflict. Mark Twain, for instance, would never make the grade. His views were too flagrant, too divisive. The same folks who quietly oppose Tubman and Douglass would loudly oust Twain as a candidate, and the nation’s conservative religious leaders would back them 100 percent.

This says a lot about us, too. Looking at U.S. money, it’s pretty obvious that cultural heroes aren’t as important as political and financial leaders to us, the American people. We, the people — not “the Man” — in the end form the nation’s collective mindset, and it’s that mindset that U.S. currency reflects and reinforces.

Plus, many cultural figures on currency potentially evoke a complex web of emotions. Imagine a $5 bill that depicted abolitionist John Brown. Humanitarians and most liberals would cheer, for sure. But American Studies scholars and key economists around the globe would immediately conclude that U.S. diplomacy was about to enter a significantly more activist and pro-human-rights phase.

That might not play well in the world market, and we are the world’s dominant currency.

What about Ralph Waldo Emerson or Emily Dickinson? In the U.S., at least, the sudden inclusion of arts heroes might signal that arts and artists rival the power of the state in the American mindset. That would be a dangerous thing for the Feds to allow for all the obvious reasons — even though our allies made this leap a generation ago.

Power rarely gives itself up.

How about Sam Walton, does he have a chance?

Where our treasure lies, so lies our hearts. Americans love success, power and the powerful. If American currency dropped the exclusivity of political figures, the next most likely group to adorn banknotes would be American industrialists, not cultural figures.

The current generation of Americans likes proposals that seem “sensible,” so auctioning off the rights to put corporate images on legal tender has a certain ring of sensibility, at least to some Americans.

But a sizeable minority of Americans would likely oppose corporate sponsorship of U.S. currency. The issue could be held up in the courts for years. More importantly, the financial community itself might find corporate sponsorship a threat to the reserve currency status of the U.S. dollar and oppose sponsorship.

It seems unlikely for U.S. currency to have sponsors. But I’d give a capitalist idol Sam Walton greater mid-term odds for appearing on U.S. currency than a cultural hero like Scott Joplin.

So we’re stuck with boring money, aren’t we?

I don’t think U.S. money will even begin to resemble the currency of our democratic allies in Europe for many years. In the short run, the idea looks unlikely. Americans still have a relationship with their government of a type that faded away in most of the other major industrial powers at the end of World War I if not World War II. We, collectively, still love the idea of a state that is the end purpose of civilization and not a mere facilitator of it.

For what it’s worth, the government’s National Research Council, in conjunction with the Bureau of Engraving and Printing, concludes that the “perfect” currency would contain the following features:

- Extremely difficult to duplicate

- Easily recognized by the general public

- Durable (remains visible after considerable wear)

- Can be machine-readable

- Easy to produce at low cost

- Acceptable to the public (aesthetically pleasing)

- Non-toxic and non-hazardous

Aesthetically pleasing is low on the list. And now you know why.

For aNewDomain, I’m Tom Ewing.

Photo credits:

Scott Joplin $10 bill, author made.

Sam Walton $10 bill, author made.

$5 bill Lincoln and the £20 Queen note composite, author assembled.

1936 stamp honoring Robert E. Lee and Stonewall Jackson.

Selma Lagerlöff 20 Swedish crown note, author collection.

Hitler postage stamps, author collection.

Mickey Mouse Bill: Scottware.com.au.