aNewDomain — I made a new friend at a conference in California. He shares a name with a medieval author, which is a big plus in my book.

We were talking about racism in the United States. Specifically, what in the world could be done about it, given how entrenched the problem is. He mentioned that in the 1960s and 1970s, civil rights protest and resistance began on and centered around American universities.

Something snapped into place for me then. Everything suddenly fit together.

For-profit universities have been dominating the higher-education landscape for about the last 10 years. Some of the basic facts are presented here without a terrible amount of editorializing. The bare numbers are fairly eye-opening, detailing a rapid increase in enrollments, income, profit and market share in the for-profit sector.

At the same time, the public system and especially the community college system have been flagging. As we get more television stations, program quality tends to go down — the market being saturated with unscripted “reality” shows and gratuitous lies (“Mermaids! The new evidence!”) to compete cheaply for a share of the ever more divided market. Schools face the same problem: competition takes students out of the seats, creating more competition for the same funding.

For-profit schools with teeth. And fins

For-profit schools are very successful by some measures. Go back to those numbers and see how many federal dollars they are capturing in student loan and grant payments. As seats start to go empty, capturing those dollars becomes a priority. And public-sector schools start to think the for-profits are doing something right. They need to compete. So they don’t become sharks necessarily, but they grow the fins. And the teeth.

For-profit schools rely almost entirely on adjunct, contingent, part-time faculty. Such faculty are paid low wages, sometimes absurdly low. They can be fired at-will or simply not contracted for future work without the inconvenience of employee rights. They are independent contractors, paid in contract terms, disposable. In recent years, as public institutions recruit management from “successful” for-profit schools (often on the direction of or under pressure from state governments taking lobbying money from said schools), this reliance on adjunct faculty has spread. As many as three-quarters of all faculty may now be contingent.

To be sure, this is a trend sweeping the employment market at large. When faculty complain about working conditions we are often seen as whiners by a labor force that in many ways seems to have it worse. But my own example is completely typical: Last year I worked two jobs and earned 32,000 dollars a year. Between two part-time jobs I taught nearly thirty classes. And I have an advanced degree — a doctorate in clinical psychology.

Fading dreams of tenure

Not only is the use and abuse of adjunct faculty on the rise, but tenure is nearly a thing of the past. Again, the rest of the workforce wonders why we think we are entitled to tenure, and even some university faculty agree. For my part, I’d be perfectly happy with the dignity of full-time employment, tenure being a long-forgotten dream.

One way to look at tenure is a system of privilege that keeps us from firing incompetent teachers. In most jobs, if you are not up to snuff, your job is in danger. That risk is thought to keep people productive. Why would you work if you could get paid for doing nothing?

This idea is dangerously false. People work because we are proud. Because we are passionate, and driven, and madly in love. We work best in secure environments, where we know we can take a certain amount of risk and be supported in innovating. Moreover, tenure requires a massive vetting process in which the candidate is screened – sometimes for several years — in order to demonstrate their worth, commitment, and competence.

Sure, we could live without tenure. Again, I’d settle for just ordinary, non-contingent employment. But giving up tenure has broader implications. Big ones.

Why I did not get arrested in Ferguson

Cornell West went to Ferguson to get arrested. He succeeded. This was not a futile or pointless gesture and was not grandstanding. Dr. West was aware of the abuses perpetrated against people of color in America when they step out of line and knew his relative fame, position, and corresponding media attention would to some degree protect the people with whom he was arrested – or, as in the case of the Selma march, focus national attention if those abuses happened regardless. He would be there to document the truth of the matter with his own body, if necessary.

I did not go to Ferguson to get arrested.

I could not afford to take a day off from work. A week off during sessions would be an absurd luxury. And I do not have tenure. If I said or did anything on a protest line that anyone found even slightly disagreeable, both my jobs would be on the line.

And if either school declined to renew my contracts, I would have exactly zero recourse. I am not an employee covered by employment law. They do not have to fire me and document any reasons, or even document no reason as in an at-will firing; they simply need assign me no classes.

This is the case for most of us now out in faculty land.

Now the United States is a place where if something is happening it generally benefits rich people. The Scott Walker government, for example, was funded by enormous campaign contributions from just a small number of very wealthy people, and breaking unions was very much in the interests of those wealthy few. Turning public opinion against teachers was a major coup, a very impressive feat of public relations in a culture that reveres teachers so highly. Suddenly the public educator was seen as a privileged elitist with unrealistic job security.

So let’s go back to the beginning.

Four decades ago, universities and colleges were the central organizing and rallying point of public protest. We got things done, too. The civil rights movement owes its existence to education and educators. The end of the Vietnam war began in free speech and free press and flourished on campuses across the country. It flourished there because schools are centers of thinking, understanding. They are where we get the facts of the matter and think critically about the world, about what we want from the world, and they are energized by youth exploring their freedom for often the first time.

A convenient coincidence

It seems too convenient a coincidence that the modern world is absent these centers for free thought and protected speech, where the faculty are too frightened for their jobs to speak out or help organize. Cornell West should have had a great deal of company from schools all across the country; the few student marches that got started here and there should have turned into a movement, been celebrated in the media. But rather than encourage such movements, support them, stand with them, we covered our asses.

That’s what we do now in America. Not just faculty, by no means only on university campuses. People are struggling everywhere. Low-wage, part time, at-will service sector jobs dominate the employment scene and nobody can afford to go on strike, and even the people who need them most denigrate the very idea of unions and collective actions.

But as my medievally-named friend in California noted, it used to be universities that were the center of the public consciousness movements that started to change the political landscape. As the public university system fails, our centers for reasoned action fail. The country falls ever more into the hands of the rich, privileged few who can afford to buy politics and who control virtually all public discourse through the media.

Maybe that’s a coincidence. Maybe there is no meaning at all in the way the public higher education is being systematically dismantled – by proponents of big business, for-profit education, and even fossil-fuels magnates. As a scientist, I don’t like coincidences but I am forced to concede that they happen.

Therefore, I cannot claim a grand conspiracy here. On the other hand, things would not be worse if it were a conspiracy.

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

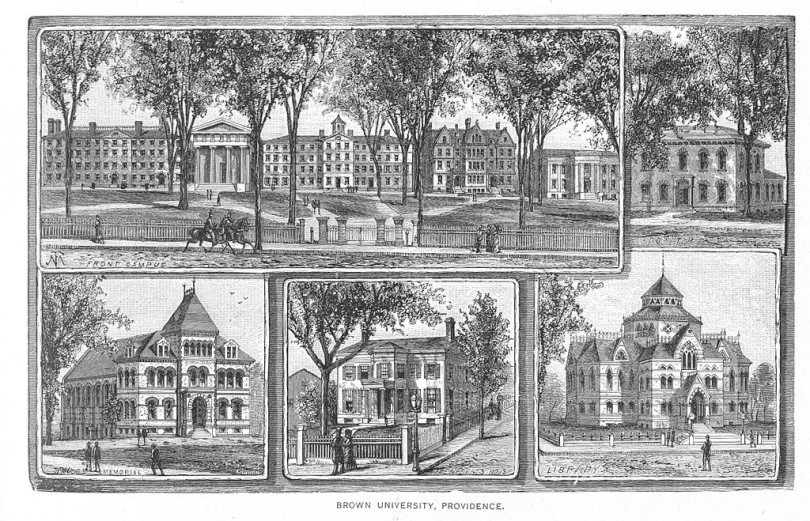

Historic 1886 engraving of buildings at Brown University, cover art: by Welcome Arnold Greene [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons