aNewDomain — I discovered Elem Klimov’s “Come and See” at the 1998 San Francisco Film Festival. I’d heard a rumor that it was Sean Penn’s favorite movie. That factoid might not seem like such a persuasive reason to see a film in this day and age, but in 1998 Sean Penn was considered one of the top three or four American film actors plying their craft.

aNewDomain — I discovered Elem Klimov’s “Come and See” at the 1998 San Francisco Film Festival. I’d heard a rumor that it was Sean Penn’s favorite movie. That factoid might not seem like such a persuasive reason to see a film in this day and age, but in 1998 Sean Penn was considered one of the top three or four American film actors plying their craft.

I was not disappointed. Truly, this is the best war movie ever made — and the best you’ll ever see.

War is a crowded film genre, but “Come and See” is so unlike any other movie ever made that it is unforgettable.

Nothing about the movie is predictable. Unlike American propaganda war pictures such as last year’s “America Sniper,” “Come and See” shatters every myth it encounters with an instinctive attraction to historical and political elements that you have never seen addressed in such personal, abstract and concrete terms. Sounds impossible right?

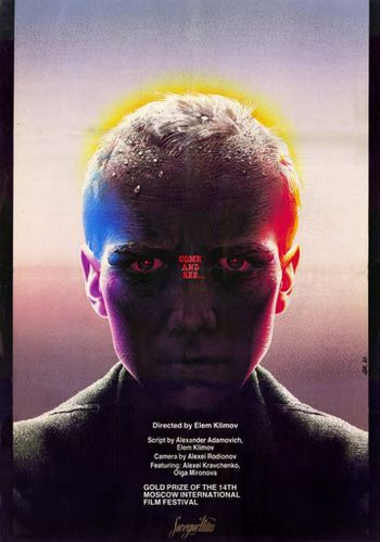

Stalingrad-born Klimov’s “Come and See” is an undiluted expression of cinematic poetry in the service of an unspeakably turbulent, fact-based, anti-war narrative about the 628 Belarusian villages burnt to the ground along with their inhabitants by the Nazis.

The film is a disorienting vision of a genocide hell on Earth that would pale Hieronymus Bosch‘s most gruesome compositions. An electricity-buzzing stench of death and social decay hangs over the picture’s constant volley between neo-realistic, formal and documentary styles that Klimov uses to convert as wide a range of specific wartime experience as possible.

The film is a disorienting vision of a genocide hell on Earth that would pale Hieronymus Bosch‘s most gruesome compositions. An electricity-buzzing stench of death and social decay hangs over the picture’s constant volley between neo-realistic, formal and documentary styles that Klimov uses to convert as wide a range of specific wartime experience as possible.

The director takes the viewer on a quicksilver descent into an existential madness of war through the eyes of his 14-year-old peasant protagonist Florya. Alexei Kravchenko’s extraordinary performance as the film’s subjective guide encompasses a lifetime of suffering over a period of a few brutal days of the Nazi invasion.

Born into a communist family on July 9, 1933, Elem Klimov’s parents constructed his first name as an acronym of Engels, Lenin, and Marx. In his 70 years, Elem Klimov made only five films: “Welcome, or No Trespassing” (1964), “The Adventures of a Dentist” (1965), “Agony” (1975) and “Farewell” (1981). “Come and See” was his astounding final picture that would establish Elem Klimov as a storyteller of untold narrative depth and intuitive sensitivity.

For the film, Klimov fashioned a detailed visual vernacular of dialectic form. His original, rigorous narrative format compresses the overwhelming heartbreak of Hitler’s war. We experience its many jolts, shocks and horrors. By the film’s end, we witness a young boy’s soul so terribly ravaged by the war’s horrors that he resembles an old man.

For the film, Klimov fashioned a detailed visual vernacular of dialectic form. His original, rigorous narrative format compresses the overwhelming heartbreak of Hitler’s war. We experience its many jolts, shocks and horrors. By the film’s end, we witness a young boy’s soul so terribly ravaged by the war’s horrors that he resembles an old man.

When Klimov sat down to write the script with his collaborator, the Belarusian Soviet author and critic Ales Adamovich, the ardently intellectual director crafted an acutely personal story about a boy who goes to fight against Nazi troops occupying his native Belarus in 1943, after joining up with a ragtag army of partisan soldiers taking shelter in the middle of a wooded area.

Objectively, “Come and See” is Elem Klimov’s brave attempt to cinematically compartmentalize and contextualize his own wartime experiences as a child escaping the battle of Stalingrad, in the company of his mother and younger brother, by raft across the Volga while the city burned to the ground behind them.

Klimov said of the indelible event, in relation to “Come and See,” “Had I included everything I knew, and shown the whole truth, even I could not have watched it.”

The director asserts the story’s peculiar social parameters with an old man holding a horsewhip while calling for two boys guilty of incessantly “digging.”

The director asserts the story’s peculiar social parameters with an old man holding a horsewhip while calling for two boys guilty of incessantly “digging.”

“Playing a game? Digging? Well, go on digging you little bastards,” the old man shouts at the boys.

From the distance arrives what seems to be a short, stout military officer carrying a stick and frothing at the mouth with recriminations for the little old man that he approaches with measured steps. We realize that the apparent military officer is, in fact, one of the little boys — speaking in a raspy fake adult voice to play his imaginary part of a menacing armed forces commander.

Exasperated, the old man who fathered at least one of the “bastards,” gets on his horse and cart, telling his defiant son that if he won’t listen to his father then he’ll “listen to the cane.” Klimov uses the vision of a young boy appearing as an old man to bookend the story as a manifestation of the war’s aging effect on its survivors.

The once-fresh-faced Florya will switch places with his young friend, whose fate falls to Nazi soldiers. The impersonating-child deliberately chooses to comport himself as a veteran soldier. For his part, Florya will have his youth stolen from him in unspeakable ways.

Florya’s smaller companion walks along the beach to find Florya laughing manically at nothing in particular while crouched down in bushes. We are introduced to Florya as a child not in control of his behavior. There is already some madness present in his manic laughter. Florya is subordinate to his peer, who orders Florya to get back to work “digging.”

Florya’s smaller companion walks along the beach to find Florya laughing manically at nothing in particular while crouched down in bushes. We are introduced to Florya as a child not in control of his behavior. There is already some madness present in his manic laughter. Florya is subordinate to his peer, who orders Florya to get back to work “digging.”

We, the audience, know already that everything is not right with the boys and their surroundings.

It’s a powerful metaphor that Klimov employs, that of the boys attempting to gain escape from the outside world by digging deeper into the earth. The oddly naturalistic scene exerts a primal human motivation at odds with the noisy warplanes that pass overhead.

Buried in the sand up to his shoulders, Florya struggles with both arms to pull something from under the sand — it appears as if an unseen monster is swallowing the boy, attempting to drag him to the depths of hell.

Buried in the sand up to his shoulders, Florya struggles with both arms to pull something from under the sand — it appears as if an unseen monster is swallowing the boy, attempting to drag him to the depths of hell.

After much struggle, Florya excitedly extracts a prized rifle that he believes will give him entree into joining a partisan troop of soldiers so that he can help battle Hitler’s rampaging armies.

A German recon warplane flies overhead to the sound of German radio-broadcast propaganda. Klimov will reuse the same archive footage of the bomber plane many times over during the course of the film to achieve a droning visual effect of an authentic historical reference that contributes to an unrelenting rhythm of sudden violence, and brutal spatial dilemmas. Already Florya’s journey is a person that we can relate to only with total involuntary commitment.

The endemic breakdown of family and society is confirmed in the next scene where Florya’s frantic mother pleas directly to Klimov’s empathetic camera for her son to take the axe that she places in his hands, to kill her and her twin daughters rather than abandon the family. Florya’s peasant mother is disconsolate as she beats him with a bundle of rope, refusing to allow him to leave.

But Florya is immune to his mother’s panic. He winks at his little sisters while he holds the axe, playing a secret game with them.

But Florya is immune to his mother’s panic. He winks at his little sisters while he holds the axe, playing a secret game with them.

Two protestant soldiers peer in through the family’s window before entering the home to take Florya to join a nearby regiment of soldiers. It is the last time that we will feel any sense of home or normal life in the film. The soldiers’ politeness turns abruptly to that of menacing authority figures taking Florya with them as a kind of willing prisoner.

In the military camp, Florya meets a lovely but deranged teenaged girl named Glasha (disconcertingly played by Olga Mironova). The wild-eyed stare of her steel-gray eyes makes Glasha as much of a monster as a would-be love interest for Florya to gravitate toward.

That Glasha, dressed in a pretty green party dress, is carrying on some kind of affair with the troop’s military chief only momentarily distracts from the extent of her mental instability — inasmuch as we subjectively bestow sanity to the partisan group’s stern military leader.

There’s contagious insanity in the air that seems to have infiltrated every character that Klimov introduces.

There’s contagious insanity in the air that seems to have infiltrated every character that Klimov introduces.

The film’s first act closes with a group photograph of the troop that provides a formal tableau of thick narrative subtext — witness a wounded soldier bandaged like a mummy and a black female cow with “Eat me before the Germans do,” written in white on its side.

Upon their departure, the ragtag troop abandons the young boy that the military chief has quietly deemed unsuitable for the demands of battle. Florya’s inconsolable anguish at being deserted by his surrogate family boils to a breaking point when he accidentally steps on a nest of eggs, killing the tiny birds in a glimpse of nature made horribly grotesque by his unavoidable human brutality.

It’s this violent and immediate style of detailed poetic storytelling that grips you and pulls at your senses with an inescapable urgency of survival. Klimov’s precise use of graphic symbolism will steadily increase to a fever pitch in the film’s stunning postmodern climax where a backward-moving collage attempts to collapse the Pandora’s box of Hitler and the war that determines Florya’s survival.

The soldiers also abandon Glasha.

The two adolescent refugees cry into each other’s eyes in a heartbreaking expression of raw emotion that Klimov captures with extended fourth-wall-breaking close-ups that intuitively editorialize on their fragile mental states.

Florya recognizes Glasha’s strange psychosis, but is unable to evade her spell.

Florya recognizes Glasha’s strange psychosis, but is unable to evade her spell.

The pity that the soldiers take on the pair, by leaving them behind, backfires when a rash of falling German artillery shells permanently robs Florya of his hearing. The bombings are especially shocking for their violent realism that arrives suddenly with large swaths of forest ripped apart by earth-quaking explosions accompanied by a high-pitched ringing that destroys Florya’s hearing and wrecks his conscious mind.

Klimov utilizes Florya’s sensory deprivation with a twisted soundscape that indoctrinates us into Florya’s pain and panic via a claustrophobic sonic space that increases our sense of being badly wounded.

The next morning, Florya and Glasha frolic in the rain in a brief reverie where they forget the impending danger that awaits them. Under the muted sounds of sped up radio music, Glasha does a Charleston-styled flapper dance atop Florya’s rain-soaked suitcase.

There’s a dreamlike quality to the couple’s short-lived musical respite before an outlandish pelican-type bird conveys an unnerving omen of unexplained incidents to follow. Wild animal life will play an important part of the image system filigree that Klimov uses to regularly connect the story to its ecological foundation in the landscape of Belarusia.

Klimov is commanding in his willingness to create abstract visual motifs, as when Florya returns to his mother’s house with Glasha and peers down into a well while looking for his family. We view Florya through the back end of an organic cinematic telescope through which he sees himself.

What Florya doesn’t see are the mangled bloody bodies of his family and neighbors piled high against the backside of what was once his family’s home. Glasha looks back and sees the carnage as they walk away from the area, but worriedly refrains from alerting Florya to the horror just behind them.

Florya runs into a thick muddy swamp that he is compelled to cross, believing that his family is hiding on a small island that he must trudge through quicksand-like mud to get to.

Glasha follows Florya into the mud and holds onto the back of his coat as they painfully make their way through the thick brown sludge. Klimov layers on subdued layers of musical textures and ambient sound to weave a theme of self-flagellation, as assisted by Belarusia’s uncontrolled topography that threatens to swallow up our protagonist and his female companion.

Glasha betrays Florya the first chance she gets when a Belarusian peasant helps her escape the mud.

The traumatized Glasha loudly explains that Florya’s family was killed, and that now he is deaf and out of his mind. Through his muted hearing, Florya hears her cruel words that Glasha speaks and reacts with a pained cry that powerfully expresses a depth of agony that imprints the film with an indelible image of victimization.

Moments later, Florya will be led by peasants to the badly burned body of his friend’s father, who speaks his last words about how he begged the Germans that set him on fire to kill him.

A crowd of desperate peasants chant under Klimov’s soundscape of blowing wind. Florya sees a trenchcoat-dressed effigy of Hitler with a human skull head that the peasants put clay on to make more lifelike. A group cut off Florya’s hair and buries it as part of a cleansing ritual that reinvents the traumatized Florya as a walking ghost.

In the third act Florya becomes a roaming independent soldier with a knack for barely escaping Nazi attacks. Florya’s participation in expediting the extermination of a cornered group of Nazis by handing a gasoline-filled can to a Nazi collaborator, is as suggestive an act as it is a literal one, for the Belarusian peasants will open fire on the Nazis before the fuel is ignited.

Florya gains a historic perspective of Hitler that knows only annihilation. His hatred and fury seeks to eradicate the world of Adolph Hitler and his armies with tremendous prejudice. With his brain and body irreversibly changed, Florya has become the only thing that he will ever be capable of being for the rest of his life, a soldier against Hitler.

“Come and See” won the Moscow Film Festival’s Grand Prize in 1985.

Afterward, Klimov was elected as first secretary of the Soviet Filmmakers’ Union and, during his two years on the post, oversaw the release of more than a hundred previously banned Soviet films.

Elem Klimov went on to struggle with the idea of creating a film version of Bulgakov’s “The Master and Margarita,” and with making a film adaptation of Dostoevsky’s “The Devils.”

However, in 2000, he gave up filmmaking because he felt that he had done “everything that was possible.” The visionary filmmaker died on October 26, 2003, and left behind a war film that accomplishes everything possible in cinema, and reinvents it.

Here’s the trailer.

For aNewDomain, I am Cole Smithey.