aNewDomain — Be warned, fair reader: There are spoilers herein. But if you haven’t finished watching Dexter or reading the Dexter series of books by Jeff Lindsay, what’s keeping you?

aNewDomain — Be warned, fair reader: There are spoilers herein. But if you haven’t finished watching Dexter or reading the Dexter series of books by Jeff Lindsay, what’s keeping you?

An existential hero is someone who strives for authenticity even when it is costly, lives meaningfully in the midst of a banal, absurd world, and confronts rather than rejects reality regardless of the personal cost.

Dexter Morgan fits the bill.

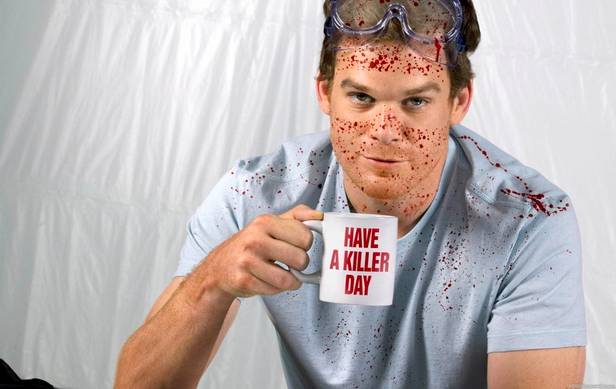

The central character of the eponymous cable show, Dexter (Michael C. Hall) is for sure more easily understood as an antihero. He’s a serial killer, confined by a code of ethics he received from his stepfather — to only kill other serial killers. He gets the bad guys that the system can’t get or won’t get. His brother assures him one cannot be a killer and a hero – the world doesn’t work that way. But Dexter is his sister’s hero — and he is his wife’s hero — and he is idolized by many.

It gets complicated here.

It gets complicated here.

We idolize many killers. Police have to kill in the line of duty; soldiers are trained to kill when necessary. Our action heroes on TV routinely rack up substantial body counts over the course of a movie or a TV series.

The fictitious ones we can let go as wish fulfillment or a safety valve. But the people who actually kill, well, conscience gets in the way.

PTSD doesn’t result only from watching mayhem, losing friends, being a victim – but also from the moral injury.

The moral injury results from crossing one’s own lines, acting in a way that conflicts with one’s own values. We’re taught young that killing is wrong and that’s a worthy thing, a great thing.

But when we do kill, that conflicts with the most basic parts of ourselves.

He’s gruesome and dispassionate when we first meet him, deliciously deranged in the grip of his “dark passenger,” the urge inside him that drives him to kill. Through the novels and the seasons, he seems to grow into his emotions.

As a man who has emotions but is unaware of them, Hall plays him to perfection.

Dexter dates a woman who has been heavily victimized in order to have cover – to seem normal – without the threat of real intimacy, and is surprised to slowly come to have real feelings for her and her children.

He watches others with a kind of mystified awe as they interact emotionally. He tries to do what others do – smile, laugh, make jokes – and the awkwardness of it all is hilarious and heartbreaking at once.

The humor in the series is as dark as in the books. One of my favorite cringe-laughing scenes happens after Dexter’s wife is murdered and he has to break the news to the children.

The humor in the series is as dark as in the books. One of my favorite cringe-laughing scenes happens after Dexter’s wife is murdered and he has to break the news to the children.

A funeral director tells him, “I’m sorry for your loss,” and Dexter marvels at his apparent sincerity. Later he says the same to the children, unaware that the line is specific to professional courtesy and that families need something more.

One of my guiltiest laughs happened watching that scene play out, watching the daughter as she begins to hate him.

Counterpoint: Dexter’s sister, Jennifer. She’s just a regular person. When she discovers what he is and, later, has to kill with him, she sustains a moral injury – several moral injuries – that are explicit in the show as leading to PTSD. Her conscience starts to get in the way. She acts badly, irrationally, self-destructively. Drugs, promiscuity, alcohol, risk, assault. These things, well, our returning soldiers struggle with them for the same reasons.

Dexter spends so long impersonating humans that he slowly becomes one. He fakes it and begins to make it. Unlike someone in a self-help group, though, he never expects to make it. He’s been taught that he is a psychopath: absent empathy or the potential for it, absent the ability to restrain his impulses – only to channel them.

It is the uprising of emotions that concerns us here.

Initially he denies them. For a while he battles against them. Then he goes along with them, for a little while.

He makes friends with a pastor, a reformed killer who helps other killers reform. He almost gets religion, toys with the idea of faith. But then the pastor is killer by one of his charges. Dexter returns to his old ways. He discovers lust as well as affection and these things end badly.

He tries to learn how to be a family man from an accomplished serial killer who seems to have a perfect family life. That is the incident that ends in his wife being murdered and his family dissolved.

More: he finds that perfect family life he tried to emulate was 100 percent fraud.

At every turn, his efforts to turn towards his humanity end in tragedy.

And at every turn he keeps turning back toward that humanity.

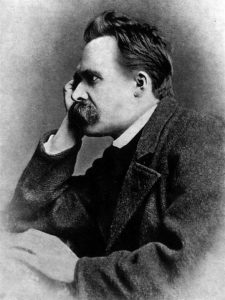

Never go against your true nature, said Nietzsche. And indeed, whenever Dexter turns away from his life as a killer, things go wrong. People die. He ruins everyone around him. Eventually, he has to turn back towards this life despite the personal cost.

Dexter’s existence is often banal and even meaningless. Chasing criminals through blood spatter analysis. Trying to fit in, to look normal. The things we all do, really – go to our jobs and try not to clue people in to the fact that we’re freaks.

Dexter’s existence is often banal and even meaningless. Chasing criminals through blood spatter analysis. Trying to fit in, to look normal. The things we all do, really – go to our jobs and try not to clue people in to the fact that we’re freaks.

But Dexter has a mission. It’s an evil mission, arguably, but a mission nonetheless.

In his world, killers know each other and cannot be changed. He always returns to killing in the end because other solutions don’t seem to stick.

And he knows he is just like all the killers. He faces these realities. He absorbs his losses. Wife, children, lover, friend, brother. Co-workers.

He knows he is at fault for most of them.

In the end, with a chance to start anew somewhere else with his son and a woman he loves, a woman who accepts him even though she knows just what he is, he pilots his boat into a storm to be presumed dead.

He lets them go because he knows he will destroy them. For him, this is a fact.

In the real world, we’d argue with this assertion. We would say Hannah, his girlfriend, and Harrison, his son, have the essential right to choose whether to accept the risk – to love him knowing that said love would eventually destroy them. In Dexter’s fictional world of more aggressive absolutes, he acts on his knowledge.

At the very end he is totally alone. Completely free. His attachments are gone. He has chosen a life of solitude, of penury, away from love not because love makes him weak, not because he can’t love, but because he loves. Deeply, intensely. He loves enough to get out of the lives of the people he loves.

He accepts the pain of loneliness, isolation, anonymity.

His mission has changed. While he may still kill, he is no longer a killer. Accepting his basic humanity opens him up to suffering and he chooses to suffer, to be human.

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

Cover image: RedBrick.me, All Rights Reserved. Dexter image inset: IMDB.com, All Rights Reserved; All other images: Jason Dias for aNewDomain