aNewDomain — Warning: This Crimson Peak review is full of spoilers. I’ll talk about inconsequential stuff for a moment while you decide whether to hang around.

aNewDomain — Warning: This Crimson Peak review is full of spoilers. I’ll talk about inconsequential stuff for a moment while you decide whether to hang around.

When I first saw previews for “Crimson Peak,” I thought Mia Wasikowska, who plays Edith Cushing, looked uncannily like a young Gwyneth Paltrow. Impossibly young. But later, through the movie, she appeared younger and younger. A design feature, a make-up induced regression, or simply my imagination at work? Whatever, by the end of the film she seemed hardly a woman, just a child.

Still here? Then I assume you don’t mind seeing plot points revealed.

This is a classic gothic horror, full of mood pieces and melodramatic romance. The script is good enough for the job it must do and the acting is more than competent, Wasikowska, Chastain and Hiddleston putting life into quite a workaday script. As you must have read elsewhere by now, though, it isn’t the script or the acting that stand out.

The real star of the show, the reason we all went to see the movie, is the direction of Guillermo del Toro.

His work on Hellboy I & II and especially Pan’s Labyrinth established del Toro as the go-to person for over-the-top, sumptuously horrifying settings, characters and effects. And what he provides here is a surrealist-Gothic wonderland, a place where the ground bleeds, where the real elements are so real that the surreal elements are totally believable. I haven’t been frightened by a ghost in a ghost story since I was nine, or shocked by violence since Hostel or, before that, Robocop. And del Toro’s realism/surrealism made a film I lost sleep over.

Yeah, a silly ghost-story script, well-acted and well dressed, did what any number of Alien sequels couldn’t do.

Some of the visuals were heavy-handed: ants devouring butterflies, a smashed-in face, the hole in the ceiling of the gothic mansion with a seemingly endless supply of leaves, rain and snow constantly falling into the house. Hair made immaculate in minutes into a style that must have taken a team of costumers at least a couple of hours.

But even the less subtle elements made an impression.

And, like a good Airplane movie, sometimes it’s what is going on in the background that is the most important.

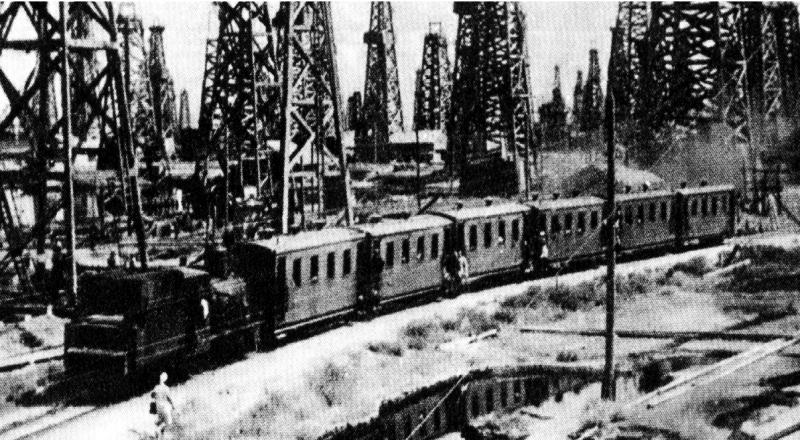

Thomas Sharpe, the male romantic lead, works through the movie on an automated mining machine. A sort of bucket system attached to a steam locomotive, the machine is among the more powerful and less subtle metaphors the film has to offer.

It runs on coal spared from the kitchen. Surrounded by the relics of former failed attempts, discarded locomotives with rusted teeth and rusted cranks, it rends and tears at the bloody ground – soil the color of open wounds.

Noisy, dangerous (it burns Sharpe at one point) and efficient, the thing is made to bring up fresh clay from mines otherwise played out, too risky to send people into.

Now one can look at this machine as a metaphor for Sharpe’s previous failed loved interests. He travels from country to country, seducing the daughters of rich men and murdering them once they sign over their assets. But four such marriages have ended thus far in continued penury, in a house that still rots around the demented, incestuous family he constitutes with his murderous sister.

The roof is broken open to the sky and the floor sinks slowly into bloody clay, the scheme a failure. The fortunes swindled away have resulted only in the broken and rusty relics that fill the yard.

When Edith moves in, though, finally Thomas falls in love with one of his victims. Her fortune never arrives; the machinery outside begins to work – and Thomas finally goes through with a marriage, properly, carnally.

When Edith moves in, though, finally Thomas falls in love with one of his victims. Her fortune never arrives; the machinery outside begins to work – and Thomas finally goes through with a marriage, properly, carnally.

His sister, Lucille, has always played the music to which he has danced, but now things finally play out as they must: an inevitable collision, a machine on a track that leads only one direction.

But behind this melodramatic metaphor is something more ominous, and the characters tell us all about it themselves. Edith says what a baronet is: someone who grows rich off the labor of farmers bound to the land.

And Thomas, under duress, tells her what she is: a spoiled child who knows nothing of real love, or of real ghosts.

Thomas is an English man who has endured privilege, who has seen what it does. His fortunes are gone, abused away by his father, and he is left with land he cannot escape. His rights are all tied up with his responsibilities in a country that did away with peonage and slavery decades earlier.

Edith’s father, Carter, played by a superb Jim Beaver, gives Thomas a self-righteous lecture about having calloused hands, about rising up out of hard work and sweat, not out of privilege and money.

But Carter goes to a club where he gives orders to a black servant. The only people of color in this melodrama, in this gothic romance, are servants, very shortly after the time of American slavery.

The machine outside represents more than the lust of one man, more than the rusty emotions grinding back into gear after decades of horror-induced numbness.

Thomas and Lucille have an incestuous relationship that parallels that of royalty of the era; the bloody ground has much to do with the hemophilia endemic to royal blood at the time. And the grinding, tearing machinery is all about Empire.

It is steam locomotives and steam ships and mechanical power that allow England to crush, grind, mine and exploit all the other peoples of the world and the nation that begins the downfall of Empire, the United States, does not do so by setting people free but by building her own empire, on the blood and callous hands and backs of her own people.

An American girl, a hale, strong youth, fights an incestuous queen in the bloody snow, ankle-deep in the gore of all the people murdered to make these empires possible, against the backdrop of a sinking house, rotting and corrupt, and whirring, grinding machinery that digs and batters against clay that can’t be told from flesh.

England is its people, not only the ground upon which it rests or the house that governs it. Thomas knows all about ghosts. England is far from blameless of the crimes of empire but America is blind as well as guilty.

Guillermo has Thomas, privileged, white Thomas, yell at us about how blind we are to our privilege, knowing we will miss the message as we always do. We’ll run upstairs, heartbroken and unimproved, while the business of empire continues unabated.

Yeah, the violence is intense, and the scenery is sumptuous, but that isn’t why a ghost story cost me a night of sleep.

Ghosts are real, Edith informs us. And they are not to be taken lightly, Thomas reinforces. But after Edith and Lucille kill each other, the machines run on and on and on, fed with coal spared from the kitchen.

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

Cover image: imdb.com, All Rights Reserved; image one: imdb.com, All Rights Reserved; image two: imdb.com, All Rights Reserved; image three: ThatMomentIn.com, All Rights Reserved; image four: coub.com, All Rights Reserved; image five: “Baku-promyselraiway” by Unknown – bdzd.narod.ru. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.