aNewDomain — When I was thirteen, my mum said: “You know something about everything, don’t you?” I recognized the insult, but I’ve always been pleased to be the kind of person who knows a lot of stuff anyway.

aNewDomain — When I was thirteen, my mum said: “You know something about everything, don’t you?” I recognized the insult, but I’ve always been pleased to be the kind of person who knows a lot of stuff anyway.

I teach a college level introduction to psychology course that spans the sciences, for instance. To teach it, I have to know about neurology, cell biology, genetics, epigenetics, natural selection; statistics, philosophy of science, philosophy generally; theology, politics, government; racism, sexism, hetero-sexism; physics, organic chemistry; linguistics, elements of sign language, anthropology and international psychology.

When you study all that stuff just to make sense of the most basic elements of human nature and the study thereof, you find that most of the reasons for what we do are unknowable.

That’s why, in psychology, we have to be at least a little bit humble. We must accept that sometimes there’s going to be more than one right answer for something, and that psychology isn’t always the best way to understand a phenomenon.

In the modern world, psychologists tend to use a bio-psycho-social approach. In other words, we understand that human behavior originates in each of those three domains.

Biology covers everything from genes to hormones, sex differences to bone structure. Psychology has to do with the internal process of a given human – something increasingly difficult to isolate and define. And sociology has to do with the behavior of groups of humans, or of individual humans in groups.

All three perspectives potentially have something to add about a given phenomenon of interest to the psychologist. Take altruism. It defiitely has important origins from the standpoint of biology. Genetically speaking, organisms that can work in teams have an advantage over those that cannot; altruism must be encoded in the DNA itself. Psychology finds that there is no such thing as true selflessness: that we do good because it makes us feel good. And sociology lends this thought: that there are always bad people adapted to take advantage of good social structures.

Who’s wrong? Everybody — at least to the extent that they discount other perspectives.

Republicans and Democrats compared:

When it comes to politics, it seems that conservatives and liberals are each looking at life through a lens that shows them an aspect of the truth — but not the whole truth. And they each tend to discount the others’ viewpoint.

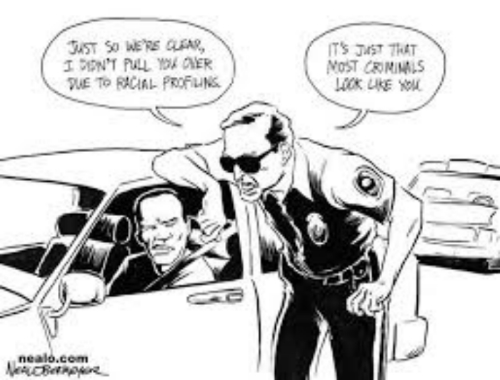

For liberals, the view tends to be sociological. Take the issues of race and economics. Liberals are much more likely to see the systems of inequity that maintain racial segregation in employment, vocation, education. Poor makes poor: Bad neighborhoods lead to schools without sufficient funding to do a good job and then lead to the problems of gangs, guns, crime and drugs. And lead to low college admissions, high incarceration rates and high unemployment.

Liberals also are more likely to understand the data when we see social psychology experiments. For example, given two resumes identical except for the name (John Smith versus Jamal Smith, for example) the resume with the ethnic-sounding name receives significantly fewer call-backs.

The conservative, however, prizing individual responsibility, lives more at the level of psychology: effort, choice, freedom, motivation. The conservative sees that black male unemployment is double white male unemployment and wonders why black folk just can’t get it together. They see those data about schools, crime, poverty and say, “I grew up poor and now I’m not.” Or say, “I grew up in a bad neighborhood and never turned to crime.” Or say, “Lots of white people are poor, too.”

Liberals tend to be as dismissive of arguments to personal responsibility. Conservatives tend to dismiss arguments to prevailing conditions.

So, who is right?

Both groups, to the extent that they dismiss the other.

This is true: While conditions for poor people are significantly harder to overcome than are conditions for middle-class people, it is not impossible to overcome those conditions.

How you read that sentence probab ly has a lot to do with who you vote for on election day.

ly has a lot to do with who you vote for on election day.

If you agree with the last clause and tend to ignore the first, you’re probably a conservative. If you agree with the first clause and feel anger or irritation about the second, while not disputing that it is essentially true, you’re probably a liberal.

Where we go wrong is assuming that one side is completely wrong. One true thing, though, is this: it’s hard to sit with the numbers all day, every day, and hold onto conservative ideologies.

The data are really, really clear at this point, and very hard to dispute. Racism is real and has many real effects on people. Sexism is real. We do in fact have double standards, and women do make less than men even when we control for time out of the workforce for raising babies.

Race is not actually a useful biological construct. But it’s a useful sociologic one because we put so much undue emphasis on it, living our daily lives with race always in mind somewhere – and the more you deny it’s on your mind, the worse you perform on tests for implicit bias.

In other words, hard work does matter.

In other words, hard work does matter.

It’s going to take hard work to get out of poverty, to overcome barriers set in place by biology, psychology, sociology. That’s true, irrefutable.

Hard work matters. It just matters more if you’re born into the favored groups – white, male, monied, straight.

And hard work is much more likely to pay off for the favored than the disfavored, and that’s ever more true as we deny it.

The math works out like this: A philosophy of personal responsibility that discounts the sociologic facts of the matter blames the individual entirely for conditions that are mostly beyond their control.

And that’s the definition of racism, right? The belief that some people are not as intelligent as others or work less, based on the race group they were born into. And it’s the belief that white people have more jobs and more money — not because of a lottery that occurred before our births — but because we deserve them.

People who are poor actually should work harder than people who are rich to get out of poverty.

If life hands you setbacks, it’s your individual choice in how hard you try to overcome them. The error in thinking isn’t in the assertions at all – it’s in the denials.

For aNewDomain, I’m not Ted Rall, which must mean I’m Jason Dias.

Image one: ArtOfManliness.com, All Rights Reserved; image two and cover: LeadFearlessly.com, All Rights Reserved; image three: lmerlobooth.typepad.com, All Rights Reserved; image four: SheNegotiates.com, All Rights Reserved.