aNewDomain — You heard me.

You watch too many Sandra Bullock movies.

Don’t get me wrong. I love Sandra Bullock. She’s funny. Sexy.

But watching these films — Two Weeks’ Notice, Practical Magic, etc. — may give you a false impression of what love means.

Is love an emotion?

Probably not. It’s not something we feel for someone that is the same across contexts. It is at least several emotions. The love you feel for your siblings — the turbulent relationship that settles down later in life to the comfortable familiarity of long-term shared experiences — must be different from the passionate or even lustful chemistry of a turgid romance. And both of those are quite different from the love you feel for your children.

Even within one category, isn’t love made up of many experiences? Your romantic love, for example, is made up of groin-oriented feelings in combination with a feeling of companionship, ease of relating, commonality, convergence of values and the ability to confide.

These are all quite different elements of a romance and might be present to greater or lesser degrees with each person you love.

And contrary to what we tell them, we love each of our children differently.

Maybe your first son you love more protectively than your third or fourth. By later in your parenting career, you have learned to be less protective, less disciplinarian or authoritarian.

Or maybe your kids all have such different personalities their demand characteristics are very different. Of course you love them differently.

So maybe love is an umbrella term for all sorts of emotions, the way anger is an umbrella term that can encompass irritation and frustration to lividness and rage. Or the way happiness can describe the mild satisfaction of winning $3 on a scratch game, or the ecstasy of seeing someone you hate get hit in the genitals with a fast-moving object, or the joy of seeing your daughter marry the love of her life.

Is love a context for other emotions?

But don’t you feel all sorts of things for and about the people you love?

But don’t you feel all sorts of things for and about the people you love?

My friend, Scooby Doo, died recently. He was part of my life for fourteen years, give or take, as good a dog as you could ask for. At times I was angry with him (when I was in graduate school, he developed a habit of chewing textbooks). At times I was proud of him, like when my then-infant son bit his ear and he just looked at the boy forlornly, knowing better than to use his impressive dentition against a small child. At times I was sad for him, as when his disease progressed to the point he could no longer eat food and the weight started to drop off, and he couldn’t climb into the car for his beloved ride any more.

I was with him when he died, at the vet’s office, with everyone — the whole family — petting him until he went to sleep for the last time, never to wake.

Sometimes you hate your parents. They say ignorant, racist stuff, and they taught you better — they taught you to treat everyone the same. You hate them because you love them. Sometimes you’re angry with them. Maybe they buy your kids expensive crap for Christmas and you beg them every year not to do that. Or you take away your kids’ phones to teach them responsibility but your folks buy them contracts.

Sometimes you are proud of your parents, sorry for them, afraid for them. And those feelings occur in the context of your love for them. The choices you make about those feelings, the way you feel the anger or sorrow, occur in the context of the love you have.

So maybe love isn’t an emotion at all, but only the context of a relationship, an attachment.

Or maybe love is a verb?

Perhaps love has nothing to do with feelings at all. The confusion of body states, attachments and other emotions we all love is culturally specific. It varies geographically and over time. Our romantic notion of finding the love of our lives and marrying for love arose in this time and place. It has to do with Sandra Bullock movies, the bridal industry, selling diamonds; it has to do with romantic stories, books, fairy tales. It has to do with entertainment and poetry.

But, as Chaka Khan once said: What have you done for me lately?

In other words, love may be a verb. It means, in that context, to put the needs of others before your own.

Love means when money is tight, you go hungry so your kids can eat a full meal. It means cheering them on at a track meet even though they aren’t great runners, taking their side in public even though they might be wrong.

Love means when money is tight, you go hungry so your kids can eat a full meal. It means cheering them on at a track meet even though they aren’t great runners, taking their side in public even though they might be wrong.

It means letting your spouse put his or her cold-ass feet on you in bed.

It means rubbing her back because she’s tired, even though you’re tired. It means listening to him, even though you don’t really like the topic he’s on.

It means going to your folks’ house for Thanksgiving even though you want to be houseproud and make dinner for a change. It means putting off buying your new car to pay for your kids’ college.

In terms of loving people generally, it means riding your bike to work when you can, rather than driving, or walking to the shops if you just need tissues and a loaf of bread. It means flushing less to save water, buying fewer plastic water bottles.

Love is what we do for one another, every day, all the time.

I’m autistic; maybe I don’t really know what love is. Don’t ask me, sis/bro. But let me ask you this: if love really is the feeling Sandra Bullock gets in the middle of the movie and has to resolve in some slapstick denouement, what good is it without the verb form? In other words, just because I have these romantic notions towards you, does that matter if I don’t follow them up with putting you ahead of me?

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

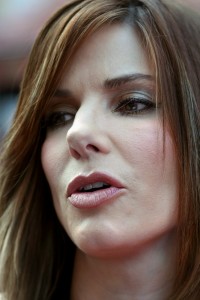

Header image: “SandraBullockLakehouse” by Caroline Bonarde Ucci. Licensed under CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image one: “SandraBullockLakehouse” by Caroline Bonarde Ucci. Licensed under CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image two: “Leno sandra bullock“. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.