aNewDomain — In the psych hospital system our model of milieu management emphasized control and containment for decades. We had takedowns and Seclusion & Restraint rooms. These were used frequently. When things were too boring on a unit, or tension was building up around the edges, the old guys said they used to defray that tension with a show of force — and by setting an example.

This was the unprovoked takedown.

About 10 to 15 years ago, we started really emphasizing patient safety. We had initiative to reduce S&R incidents and takedowns became therapeutic holds, also discouraged. We taught and learned soft self-defense: Vow to not get punched and secure a situation without hurting anyone, all with minimum risk.

About 10 to 15 years ago, we started really emphasizing patient safety. We had initiative to reduce S&R incidents and takedowns became therapeutic holds, also discouraged. We taught and learned soft self-defense: Vow to not get punched and secure a situation without hurting anyone, all with minimum risk.

Those initiatives have largely been a success. The number of acts of violence between staff and patients is radically less than it was 60, 40 or even 20 years ago. And now, as the old-line staff retire or die, that number should continue to decline. These people will be replaced by people who just understand this is how we do business, not a “new” way we should resist because our hair is gray.

I remember a giant who came to live on our unit for a few days. He was only about 5’10” but he worked out all the time, had Schwarzenegger shoulders but Johannsson ankles. He had a nasty reputation, came to us by way of another state. They couldn’t work with him, so they put him on a bus to anywhere he wanted. Our bad luck.

The guy was trouble. He tried to get what he needed with intimidation, was full-on antisocial with us. Most of the staff hid in the nurses’ station and planned how to take him down when things got violent. Go for the legs, they said; friends don’t let friends skip Leg Day, but this guy obviously had no friends.

We had massive confrontations at medication time. All the safety officers came up, there was a giant standoff. Eventually he agreed to take his pills if he could smoke – nobody smoked at the hospital. But we let him.

On day two, though, seeing how our visitor affected all the other patients, I decided to try a new approach. Actually, the approach we were being paid to take but were too scared to try.

So I went out and talked to the guy.

He was suspicious at first, squared off with me like we were going to Fight Club our relationship. But I sat on a couch, invited him to do the same.

Sitting down was not as scary.

The guy leaned forward, elbows on knees, tense. I made myself relax, sit back, cross my ankles. “Hey, dude,” I said. “We can’t go on this way. You’ve got everyone scared of you and that’s no good for anyone. Look, here’s the game. Go to a couple of groups, make nice, they’ll let you out of here in a couple of days.”

He presented his list of demands. I explained the reason he didn’t have everything he wanted was just that he squared off with people and demanded it. Except for smoking and leaving the unit, everything he wanted was on the schedule.

Then we were cool.

I basically ran the floor because nobody else really wanted to come out of the nurses’ station, but we were cool. Then our state did what the last state had done. The choice was put him in jail or put him on a bus, and there was nothing serious enough to charge him with, so he got Greyhounded out of our system.

What is illustrated here is that the patients never needed the violence used against them. They did not need to be controlled, taken down, tied up, locked away. They needed to be included, talked to, understood and loved well.

We predicted the end of the world when we were asked to hurt people less. The end never came. It’s going to be the same out there, in the world. When police no longer have recourse to firearms for every situation, they will have to learn to talk things down, sidestep conflict, control — when control is necessary — with safe techniques rather than pain.

The soft model in the hospital system required one thing over everything else in order to succeed: a relationship with each patient.

It’s well-known in therapy circles by now that what kind of therapy we’re doing is much less important than that the therapist and the therapy-goer have a strong relationship. The relationship heals, and the therapy is like the game of Monopoly you play that gives you an hour or so to hang out together. Our problem in the hospital since 1940 was we were using a police model, not a therapy model: we give drugs, hold groups, set schedules, takedown and seclude for control, not to make anyone better. In the modern world, we’re doing what we can to get past that history and move into a therapeutic model. And if we want to help people, it is going to be the relationship that does it.

The trouble with police right now is they’re also using a police model. They ask for and receive military hardware. Vests, helmets, riot shields, armored personnel carriers, tanks, assault weapons, military training and tactics. These all point to a policy, a strategy, of containment and control.

The Baltimore curfew worked. People were cordoned off, sent home, these orders enforced by police in riot gear and soldiers from the National Guard. Sent to keep peace, restore order.

Take control.

But the problems aren’t solved. There remains racial strife enacted through de facto segregation and crushing poverty. A solution to the problem is not going to involve taking control — seclusion and restraint are a failed policy, a failed strategy, inhumane and increasingly illegal. The problem is going to be solved by teaching police ways to solve problems without controlling people, and especially with recourse to the use of force.

It is going to be solved by the relationships you’ve heard so much about on the cable news. By people understanding one another, empathizing, listening well.

People need to be heard. And, in the end, the measure of whether people are heard is whether some action is taken, some relational, empathic action to make things better.

Jobs. Ending intimidation and harassment. Not using the back of the police van as a Fourth-Amendment violating punishment.

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

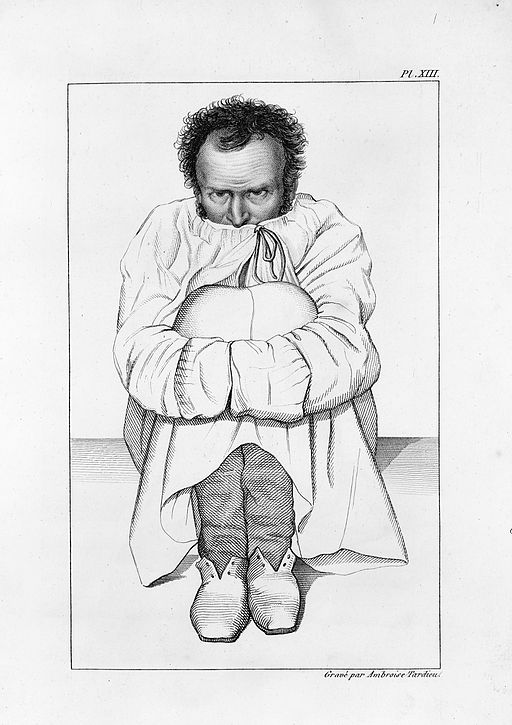

Inside image: Public domain image of Alabama Insane Hospital, circa 1909, via Wikimedia Commons

Cover image: [CC BY 4.0], via Wikimedia Commons