aNewDomain — Recently, I wrote a bit about the statistical refutation of libertarian philosophy. A friend (who is a politician and was perhaps trying to change the subject) asked, but can you really evaluate philosophy statistically?

— Recently, I wrote a bit about the statistical refutation of libertarian philosophy. A friend (who is a politician and was perhaps trying to change the subject) asked, but can you really evaluate philosophy statistically?

This raises a corollary question: What else might be the purpose of statistics?

Ideally, statistics have no purpose. The utility of the vessel is in its emptiness. One approaches reality with the closest thing possible to objectivity, asks questions, obtains data, and lets stand (provisionally) those theories that survive attempts to falsify them.

When we approach statistics with a purpose, this quickly becomes a dubious way of knowing. Statistics don’t lie but people do, using statistics – even people who think they are telling the truth.

From trolling to confirmation bias to simple misunderstanding, there are many ways to misuse statistics — as there are any faith system.

Stats, though, have a great deal to do with uncertainty. What can be known? Epistemology asks the question but does not provide the answer, only limitations. You can know nothing at all, really, not with certainty. You cannot have certainty because information exists and information changes over time. What is certainty if not the decision to refuse any further information?

The judge brings down the gavel and issues a verdict. That is certainty. This person is guilty, that one innocent — the truth of whether they committed the crime of which they are accused, that cannot be known, only judged to be beyond a reasonable doubt.

The judge brings down the gavel and issues a verdict. That is certainty. This person is guilty, that one innocent — the truth of whether they committed the crime of which they are accused, that cannot be known, only judged to be beyond a reasonable doubt.

And only particular information is admitted and considered, other information deemed inadmissible, or simply unknown. We didn’t know how to ask the right questions to elicit the testimony.

This is statistics. We ask a question, devise a way to get numerical answers to it. And we know it is possible to get results due to error, and that there are statistical artifacts like regression to the mean that make our data seem more or less impressive than it really is.

With all sorts of safeguards to the integrity of our data, finally we are willing to assert: These two phenomena seem to be related; this variable seems to be changing over time. Or, with extreme care, even that x seems to cause y.

But humility is always needed in such assertions. Error exists. So does bias. Human failings, like a failure to ask corollary questions, have us chasing down the wrong phenomena. How much time have we wasted pursuing ghosts, aliens and monsters?

Well, none, really. Negative results are results, are they not?

Stats are really about this, about uncertainty. About there being no final, definitive, concrete answers, only more refined questions and investigations that lead to better data. Is evolution true? Well, we can’t say for sure. We can only say that we’ve attempted to falsify the idea and, so far, there are no better contenders that have withstood as many attempts.

Now with all of this philosophy, this acceptance of ambiguity, we turn our eye to other branches of philosophy. Politics and religion are particularly pernicious habitats of certainty and what we find, with our epistemology of uncertainty, is that such certainty is generally undue.

Now with all of this philosophy, this acceptance of ambiguity, we turn our eye to other branches of philosophy. Politics and religion are particularly pernicious habitats of certainty and what we find, with our epistemology of uncertainty, is that such certainty is generally undue.

The way people have decided their beliefs has little to do with a rational examination of the facts and much more to do with cognitive dissonance, nationalism, inherent bias. I can’t answer with statistics such questions as is there a god, but it is certainly possible to examine the claims made by religious texts — the specific ones.

The Old Testament is not only falsifiable but falsified: The data support deep time rather than literal biblical creation. Equivocating arguments, sophistry and apologetics are necessary to answer otherwise.

Thus it is with philosophy. “All people are essentially good.” That’s a philosophic statement, and it is open to investigation. First, we have to define “good.” Then we can test whether some people are not good, and how they got that way.

Statistically, we can demonstrate that people make less ethical choices as they grow in wealth and that religion is tied to racism. People are not inherently good by these standards; they are easily corrupted by money and privilege.

We can also falsify the idea by studying the behavior of babies: they are inherently racist, as it turns out, a point I’ve made more than once.

So the philosophic precepts of a political position like libertarianism are easily investigated and refuted by statistics. The basic statements — that people act in their best interests, that charity is best left to individuals, that people will tend to behave in rational ways that are good for the collective — these philosophical elements of a political ideology are falsifiable and falsified.

There really is no better way than stats to evaluate a philosophy. That doesn’t mean statistics is a great way, it just means all other ways are worse. They appeal to our nationalism, our inherent biases.

They lead us away from considering ideas case by case and towards accepting a whole platform even though some planks are weak. We change our minds on the weak planks rather than seeking a better candidate.

We do things based on tradition and ideology, making the decision to discount all new information.

If the Bible is literally true, then nothing we have tried to do in the last four thousand years has been good for anything. No new information is valid. And then there is no point asking any questions.

If philosophy cannot be checked by statistical reasoning, then why bother to reason at all? But we have to, because all philosophic statements are otherwise equal.

In which case I have no reason to prefer an inclusive faith over an exclusive one, or to favor integration over segregation, or to favor democracy over totalitarianism. Without stats, I cannot even begin to discover what results in the most good for the most people.

And isn’t this a common goal in most religious and political and philosophic systems? The most good for the most people?

Yes, good is arbitrary and our measurements are imperfect. But what else are you going to stand on? How else to evaluate principles?

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

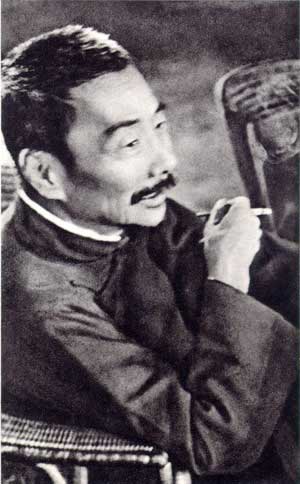

Cover image: Public domain via Wikimedia; image one: by unattributed (Christie’s) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons; image two: by Anonymus [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons.