aNewDomain — As we near the moment of the Ghostbusters movie reboot parade, I’m reminded of the “Slimer” character. By an incident in psychotherapy.

aNewDomain — As we near the moment of the Ghostbusters movie reboot parade, I’m reminded of the “Slimer” character. By an incident in psychotherapy.

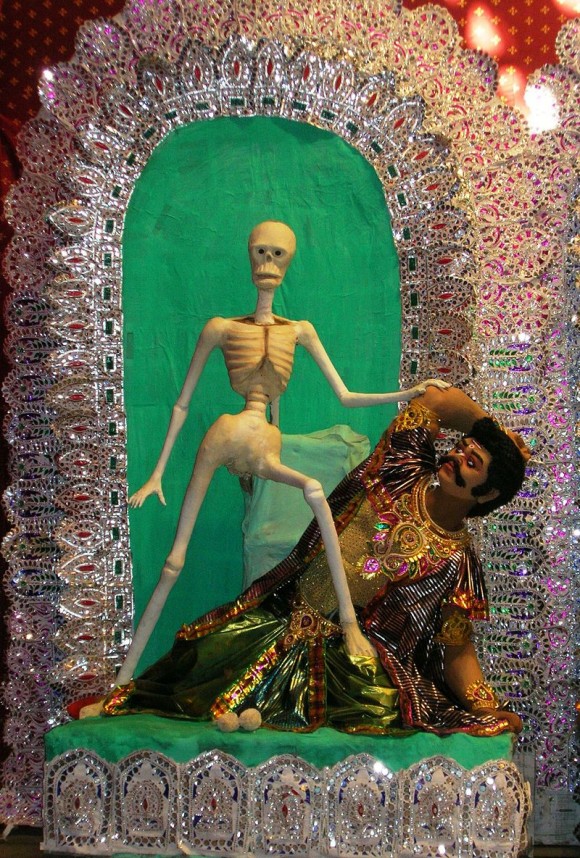

Chinese Buddhism and Taoism imagine characters they call hungry ghosts. These beings are departed souls too tormented to leave the world, who linger on and on past their time. They might haunt the edges of towns, never really able to go in, unseen during daylight and only partially at night. They might be very thin, emaciated, despite always having their mouths full of food.

They might feed on the dead or on garbage but the theme is always the same: hunger.

We currently suffer a glut of such images. Since the advent of the zombie movie, popularized if not exactly invented by George Romero, zombies have been steadily gaining acceptance until we can see them starring in their own television series. And, like vampires, some directors have even tried to make them “sparkly” (e.g., Warm Bodies).

Zombies eat the flesh of the living and are never satisfied and might eventually be reduced to skeletal forms.

The hungry ghost, though, is not so brutal, is more spectral. Zombies can get in. They will batter their way through fences, walls, chains, to devour you.

Even the Pirates of the Caribbean are not just the right movie reference. Those fellow are always hungry, and food turns to ashes in their mouths, and they are skeletal in the moonlight … but they are far too rapacious.

No, Slimer is the perfect illustration.

Slimer is the green, legless “spud” who appears as the Ghostbusters’ first paid case. It roams the halls of a hotel, snatching up whatever food it can find and stuffing its face. But it can consume nothing, being spectral. It is eternally hungry.

And, when cornered, it charges right at Venkman. It cannot really touch him or harm him, just passes on through, but it leaves him covered with disgusting slime. Ectoplasm. And Venkman says, “I feel so funky.”

We’ve all met this character in psychotherapy.

Food is love, an easy metaphor. Some heavy people like me take that a little bit literally and that’s fair, but we really are after the metaphor here. The hungry ghost in Eastern mythology has committed some human crime or sin: of lacking generosity, or of violence. Or sometimes they have merely run out of ancestors. Now they are condemned to always seek out the food they denied others. In other words, to be unloved on Earth. Starve not for sustenance, but for the sustenance of relationship.

When this person shows up in therapy, your first reaction is to note that they seem needy. The session progresses and, when it’s done, you feel unclean. Funky. Like you need a shower. The person has tried to touch you, to make unwelcome physical contact. A hug too long, too insistent; a touch of the hand that seems, well, manipulative. Slimy.

They’re hungry. They feel unloved and they need to feel the opposite. They need sustenance very badly indeed. Like the vampire, they will feed on you until you die. Like the zombie, they will consume you. But they are the hungry ghost.

They are Louis Tully (Ghostbuster neighbor and accountant), the original life hacker, some say.

He waits in his doorway for you to come home. When he hears you in the hall, he pretends he was just coming out for something, that he ran into you by accident. But really he’s stalking you. He needs something that you have. He seems pathetic and that’s more than an act: It’s a profession, a state of being.

You try to scrape off his increasingly desperate ploys for attention but he grows ever more disturbing, even monstrous.

Ghostbusters is about all the things you think it is about. And it is about this, too. Nearly every main character in the story is a hungry ghost. Spengler puts up with a lot of abuse because he is lonely, a misfit. He accepts love in the form of a candy bar, the odd backhanded compliment. Stantz takes out a third mortgage on a derelict building in the name of approval. Zeddmore will sell out his most basic beliefs for acceptance. Venkman substitutes sexuality for human contact, and Dana Barrett spends most of the movie scraping Venkman off, pushing away his semi-unwelcome contact.

She might be the only sane person in the whole thing.

At the end of a therapy session, we really want to contain the person. We don’t have confinement beams, nuclear accelerators, or storage grids in the basement. We try to set appropriate boundaries instead. It works sometimes. Other times, the person abuses our phone. They call at all times of day and night, seeking approval, seeking validation. Are you still there for me? How about now? Or now?

A student recently asked how to deal with such a person, with such a hungry ghost.

In Chinese tradition, the custom is to feed them. Leave offerings.

In psychotherapy, the solution is the same. It seems like they will bleed you dry by they can’t, not literally. You just have to be patient. It’s all right not to like clients sometimes. Positive regard needn’t always extend towards positive emotional responses. Love is not a feeling. Supply the food they need. Don’t try to force independence. Be patient. And, above all, have compassion.

These aren’t ghosts at all but people, real people. They can be loyal, charismatic, funny, brave.

Tully climbs out on the ledge to try to unplug Barrett’s cable, a risky and stupid act but ultimately a courageous and giving thing to do.

Try to see the whole person and not only the wound.

Therapy isn’t about dressing wounds or healing them so much as it is about helping the person grow to encompass the wound. To find meaning in it, in surviving it. To make a beautiful scar. And in this case, the wound is self-defense. By provoking rejection, the person can prevent rejection. If you’re never close, you can never leave them. So you have to get past that oily, slimy feeling, too find compassion, in order to nurture the rest of the person – the brave, loyal, giving person who would stand on a ledge for you, not for your approval but for your well-being.

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

Cover image: Moviepilot.com, All Rights Reserved.

Inset image: “Bhuta College Square Arnab Dutta 2010” by Jonoikobangali – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.