aNewDomain — Someone answers my call and says “Hello.” At least I think they do. I can’t really be sure.

aNewDomain — Someone answers my call and says “Hello.” At least I think they do. I can’t really be sure.

I begin talking, firmly and clearly, “This is Lamont Wood, calling for Epistemology Age. I’m doing a story on knowing what is known … or otherwise. Would this be a good time for an interview?”

And then comes the moment of truth.

“Gallup seismic porcupine,” the other person seems to say, his or her voice meanwhile constantly changing pitch and cadence while kettledrums seem to do a glissando in the background. Then there’s the muffled sound of someone teaching cats to howl pop tunes. That goes on for a while. Then there’s muffled traffic noises. Suddenly the muffling falls away.

“…proves the existence of reality. But you knew that,” the other person concludes.

“Excuse me—you were breaking up. Could you repeat that?” I ask.

In response there’s a sound like a drunken elf at the end of a rain pipe trying to imitate a bus changing gears. Then there’s the sound of a sawmill collapsing in a hurricane. “Gargle aluminum hyperextension … as I said before,” he finally adds.

“I understand,” I say.

Because I do understand. I understand that this person has a cell phone that he does not know how to use and he’s using it in a place where it should not be used. And he has probably put it in speaker mode.

This conversation might as well be taking place in the engine room of an aircraft carrier.

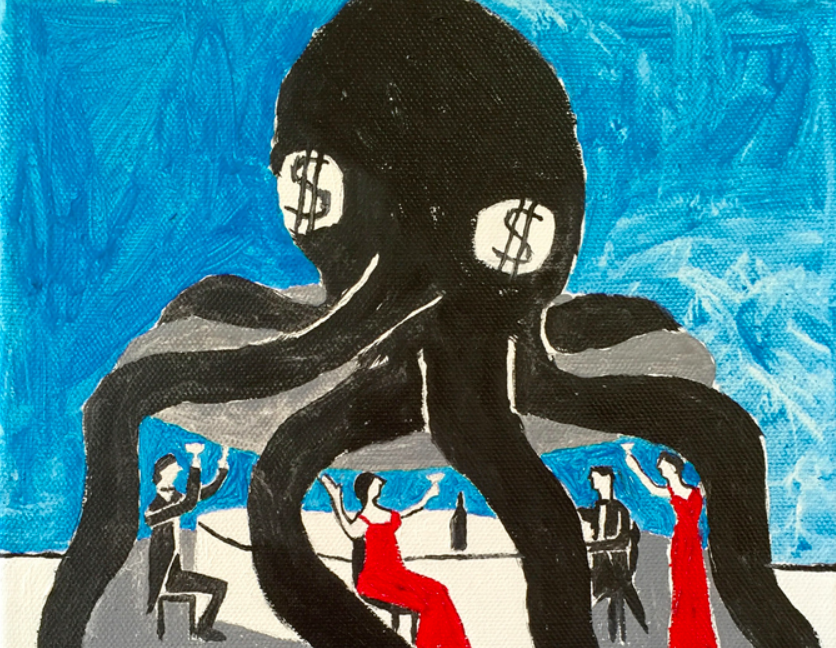

As you see, we’ve devolved into a nation of haves and have-nots — and I’m not talking about money, power, access to affordable health insurance, child-like faith in the Republicans or anything superficial like that. No, the real divide is between those who are equipped to communicate verbally at a distance and those who only think they are.

The haves are those connected by a landline to the public switched telephone network (PSTN). Now, the PSTN has accumulated some bad karma. For generations the phone companies put basic but reliable devices in homes and offices and milked the monthly rentals. Meanwhile, they smiled big and pretended they were a sanctioned monopoly that was morally justified in banning the connection of anybody else’s hardware to their network.

Their idea of customer service was to put up a sign saying “Line Forms to the Left.” When you reached the front of the line they tried to get you to add a second phone for your bathroom.

Maybe the public was cattle to put up with it. But you can understand why some would continue to use landline phones — because you can understand them. But with the Carterphone decision in 1968, the courts discovered that the phone companies were not, and never had been, sanctioned monopolies. The moralizing abruptly ended and suddenly anyone could sell devices that connected directly to the phone network. In fact, some eventually discovered they could erect cell towers, connect to the PSTN and call themselves a phone company.

And so now we have the have-nots — millions of people walking around with cell phones. Their batteries die suddenly, they lose their connections if you take a back road, they get lost in the laundry and, by the time you fish a ringing phone out of your pocket to answer it, the call has probably gone to voice mail.

Worse yet, they display Caller ID, so you don’t know if an unanswered call means the recipient is snubbing you or whether he’s lost his phone in the laundry or his pants.

“Why? Were you worried?” some kid said to me recently when I complained of his not answering his cell phone. “You could hear it ring, so you knew it was on. When you’re arrested the first thing the police do is turn off your phone, so you knew I wasn’t in jail …”

True. But if they do answer your call, they’re probably standing beside a jackhammer or sitting in the back seat of an open cockpit biplane or a sports arena. Or maybe they haven’t figured out which end to talk into …

Of course, there’s that alternative. Texting. Alas, the keyboards, if you can call them that. They are so obviously designed for diminutive young ladies with boney fingers — that’s who you see texting in public places, right? As for others, they ought to consider switching from sending pictures of body parts to sending pictures of scrawled messages. Or maybe just scrawl a five-by-five grid and put a letter in each cell, A through Z, with I and J sharing a cell. (They’ll get along fine.) ABCD would be in the top row, VWXYZ, would be in the bottom row and so on. And then, when you establish connection, you could just start tapping out the message on the mic, representing each letter with two series of taps indicating the letter’s position in the grid, row and column. A would be one tap and then one tap. E would be one tap and then five taps. N would be three taps, then three taps. You get the idea.

Yes, this method — called the Prisoner Code or the Tap Code — is klunkier than Morse code. But you don’t have to spend weeks learning it. You can scrawl the diagram anywhere. And you don’t have to look at a tiny keyboard ever — or talk over a jackhammer.

That’s right. Personal wireless communication is truly possible in this day and age. Think of the possibilities.

For aNewDomain, I’m Lamont Wood.