aNewDomain — The issue of sentience is a prickly one in psychology. No part of the psychology text I use to teach my class deals directly with the issue of sentience. Consciousness gets a couple of mentions, sentience none at all.

aNewDomain — The issue of sentience is a prickly one in psychology. No part of the psychology text I use to teach my class deals directly with the issue of sentience. Consciousness gets a couple of mentions, sentience none at all.

We’re unable to imagine any really good definitions or measurements for sentience. And measurements are useless without definitions.

We’re unable to imagine any really good definitions or measurements for sentience. And measurements are useless without definitions.

We reify our concepts all the time in psychology. This means we take our abstractions and treat them as real things.

Consider intelligence. We started measuring it on the assumption it was a real thing in the world, but we didn’t do a great job of defining it first. So we ended up with a weird tautology, namely: Intelligence is that which is measured by intelligence tests, which are instruments that measure intelligence.

Intelligence, personality, mental illness and wellness, all are concepts heavily reified by psychology. These ideas can have real-world implications as our reifications become instruments of oppression. In particular, a person’s mental health status can become a point of intervention. Those interventions might be intrusive and less than gentle, such as incarceration and forced medication, including injections. But what about consciousness?

Is consciousness a real thing?

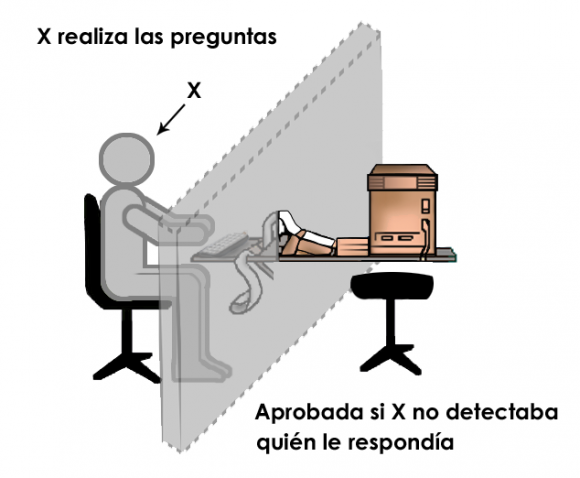

Turing’s test is pretty famous by now. The question is, really, whether Turing understood the phenomenon he was attempting to test for. His idea was that a human would interact with an artificial intelligence without being able to see the entity. If the artificial intelligence could convince the person it was a person, then it would have achieved intelligence.

Is this consciousness – the ability to seem conscious?

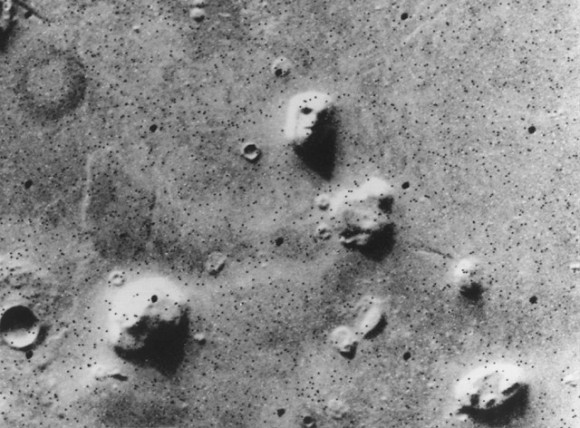

The thing is, people are over-specified to detect consciousness the way we are over-specified to detect faces. We see faces everywhere because they are a central feature of our existence. Faces tell us who is friendly and who is a stranger; who is like us and who is different; what people feel, want, are thinking.

So we see faces not just where they really are – on the front of human heads – but in the arrangement of headlights and bumpers on the front of cars, in the windows and doors of homes, on Mars.

It’s called pareidolia.

It’s called pareidolia.

We see consciousness the same way. We’re over-specified to interact with conscious beings. So we talk to babies, cats and dogs as though they can understand us. We talk to the television as if the characters can hear us. We yell at players on our favorite team, shouting encouragement or warnings. We talk to the car when it won’t start, the lawn mower, even the coffee maker (“Brew faster, if you want to keep working in this  kitchen …”).

kitchen …”).

We see order in random events, and blame that order on some universal agency.

Like a cosmic joker.

The apparent irony of life seems to be the outcome of a grand design. You spend an hour doing your hair for a wedding, then a gull shits on your head as you get out of the car. Figures.

Well, strictly speaking, it doesn’t. It doesn’t figure at all. You want to blame an agent for your misfortune, but there is no agent to blame.

How to make your machine aware of itself

So, consciousness. Take your laptop. Plug in an external webcam. Point the cam at the laptop. Tell the computer to look at it. Now the machine is aware of itself. It can see itself in the cam.

If consciousness is merely awareness of self and environment, then your neighbor’s pretentious luxury car is conscious. It sends out tweets about its maintenance status and monitors radar for impending collisions.

If consciousness is merely awareness of self and environment, then your neighbor’s pretentious luxury car is conscious. It sends out tweets about its maintenance status and monitors radar for impending collisions.

Sentience is a necessary ingredient to consciousness. Consciousness must include a self of which to be conscious.

The self is another sticky wicket, though. Is it real? Is it more than the illusion that arises from a consistent memory of one’s integrated experiences over time combined with the idea we consciously made decisions and enacted them?

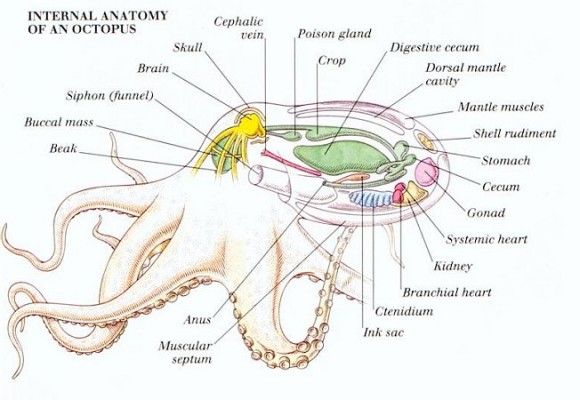

I mean, look at this octopus.

Is this a sentient being? It must scan the environment, understand the terrain, understand the ways it’s body is like and unlike the organisms it mimics. It makes decisions about what color and shape to be and can imitate new things – it isn’t merely programmed with a few basic shapes it can do.

It can learn new creatures.

Cephalopod intelligence is a thing to wonder at. The animal doesn’t have a brain the way humans do. It has a nervous system more  distributed than centralized but intelligence seems to arise from this system as much as from ours.

distributed than centralized but intelligence seems to arise from this system as much as from ours.

Birds have tiny brains compared to people, even when considered as a percentage of body mass. But birds have long shown great cunning and problem-solving skills.

Consider the crow in the video below.

Turning’s main mistake seems to have been to assume humans are sentient and nothing else is. Why is fooling a human the benchmark for artificial intelligence?

Why not consider a different construct? Why not consider sentience in a new and different way?

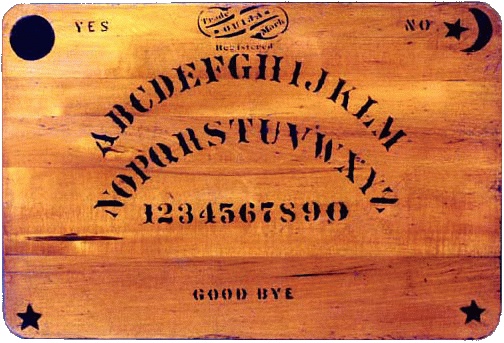

What’s more sentient: a cow or a Ouija board?

Humans are easily fooled but also stubborn. When studying the minds of animals, for example, we know we can’t have the experiences of dogs or monkeys or apes, so we are careful not to ascribe their apparent grief to actual grief or apparent comprehension of language to actual symbolic comprehension but merely to behaviorist stimulus-response paradigms.

We won’t say a cow has sentience, but we’ll say the planchette of a ouija board has it, that it is controlled by spirits. We give sentience to things we can’t even see, whose existence we can’t even verify (ghosts) but not to elephants that visit their dead relatives to touch their bones.

We really want to be different from animals, and this might be part of the problem. Trouble is, we don’t really have any quantifiable traits that other animals don’t share at least in small ways. Groundhogs have language, rats have a sense of empathy, dogs and monkeys go on strike if they see another animal getting more for the same work.

We really want to be different from animals, and this might be part of the problem. Trouble is, we don’t really have any quantifiable traits that other animals don’t share at least in small ways. Groundhogs have language, rats have a sense of empathy, dogs and monkeys go on strike if they see another animal getting more for the same work.

Definitions of consciousness that include our non-human companions on Earth necessarily make us uncomfortable. We haven’t even managed equal rights and protections for all our human brothers and sisters. Assuring such things for dolphins, elephants and dogs seems undue under the circumstances. But if fish feel pain, is it ethical to catch them on hooks for sport, release them, and catch them again?

People think all the time that their pets understand them. A test for intelligence, consciousness, or sentience that includes humans seems like it must always wind up catching things in the net that we want badly to throw back. So we have to be careful our definitions don’t exclude ourselves.

How about: sentient beings are capable of recognizing sentience in other beings.

How one would know that the being had correctly identified sentience is the stickiest of all the wickets, perhaps. But empathy would be a good start, and we can operationalize empathy: the empathic being refrains from harming beings capable of understanding that they are in pain. And it errs on the side of caution.

If this leaves you out, I’m sorry: you might not have achieved your optimal level of consciousness.

And if all this seems pretty murky, maybe it’s meant to.

Too easy an understanding of sentience, consciousness or intelligence is a dangerous understanding, one that reifies, and potentially one that oppresses.

So let’s throw some mud in the water by ending with the parable of the fishes.

The Happiness of FishZhuangzi and Huizi were strolling along the bridge over the Hao River. Zhuangzi said, “The minnows swim about so freely, following the openings wherever they take them. Such is the happiness of fish.”Huizi said, “You are not a fish, so whence do you know the happiness of fish?”

Zhuangzi said, “You are not I, so whence do you know I don’t know the happiness of fish?”

Huizi said, “I am not you, to be sure, so I don’t know what it is to be you. But by the same token, since you are certainly not a fish, my point about your inability to know the happiness of fish stands intact.”

Zhuangzi said, “Let’s go back to the starting point. You said, ‘Whence do you know the happiness of fish?’ Since your question was premised on your knowing that I know it, I must have known it from here, up above the Hao River.”

~ from Zhuangzi: The Essential Writings With Selections from Traditional Commentariesby Brook Ziporyn ~

For aNewDomain, I’m Jason Dias.

Image one: Pinterest.com, All Rights Reserved

Image two: Study.com, All Rights Reserved

Image three: “Prueba de Turing” by Mushii – Own work. Licensed under CC BY 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Image four: by Viking 1, NASA [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Image five: “Größte Kaffeekanne Selb” by Stern – fotographed by Stern. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

Image six: RedBubble.com, All Rights Reserved.

Image seven: Cephalove.blogspot.com, All Rights Reserved.

Image eight: MuseumOfTalkingBoards.com, All Rights Reserved.