aNewDomain — So your company’s top researcher quit in June to take a new job at a competitor as vice-president of research. Fair enough. But in August, all the engineers working on your most promising new product leave en masse to work at the same competitor. What are you going to do?

You call your lawyer and talk about suing — for theft of trade secrets.

That’s your easiest legal remedy and your best cause of action. You need to put those stray ex-employees on notice, even before you start figuring out what exactly they might have stolen.

That’s your easiest legal remedy and your best cause of action. You need to put those stray ex-employees on notice, even before you start figuring out what exactly they might have stolen.

It’s a course of action that might even keep them from spilling still more magic beans, even if those magic beans exist only in their heads.

The trade-secret remedy also comes in handy when you need to protect your company from the damage employees accidentally do, like letting slip secret prototypes in a bar, hotel room, convention center or some other place they shouldn’t be outside the facility.

What’s a trade secret, really?

A lot of people think a trade secret has to be technical, like what chemical re-agent your detergent is using or what code powers the DSL chips in your hot new gadget.

But even customer lists and customer survey data counts as a trade secret. If I’m selling pound cake, knowledge about my customers’ preference for intensely yellow cakes counts as a trade secret, too, especially if you happen to know that intensely yellow cakes generate 25 percent higher sales.

See, the legal definition of a trade secret is really broad. Any information that’s not public and has economic value to the company potentially qualifies. Key employees, especially key technical employees, salespeople or other folks privvy to your secret sauce, probably do hold your trade secrets, even if those secrets reside only in their heads. People who pioneered new technology, strategies or methods on your dime also hold intangible assets in their heads. Those assets belong to you, and they’re valuable.

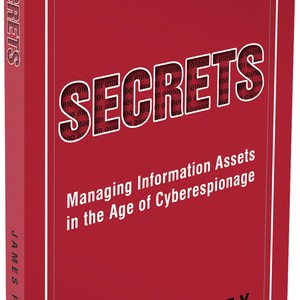

You need to protect your valuable human capital assets, says Silicon Valley litigator Jim Pooley in his new book, Secrets: Managing Information Assets in the Age of Cyberespionage. It offers an excellent, plain-English summary and starting point for understanding the basics of corporate trade secret protection and how to put in a robust trade secret protection plan in your company.

You need to protect your valuable human capital assets, says Silicon Valley litigator Jim Pooley in his new book, Secrets: Managing Information Assets in the Age of Cyberespionage. It offers an excellent, plain-English summary and starting point for understanding the basics of corporate trade secret protection and how to put in a robust trade secret protection plan in your company.

Sample consulting agreements, sample non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) and sample warning letters to departing employees are just a few of the handy tools you’ll find inside.

“More than anything, protecting trade secrets is about managing people,” says Pooley, adding that “your company should really create an information protection plan.”

Why corporate spies steal your trade secrets

Used to be, the only effective way for a competitor to snag your trade secrets was to physically break into your facilities or bribe one of your less loyal employees. No more.

“Because more and more company information resides on computer servers that are accessible over the Internet, companies now offer nearly infinite portholes for theft,” Pooley says. That explains the relatively recent jump in computer espionage incidents.

Pooley adds that the advent of cloud services has further fueled corporate spies with more ways to filch your most important company secrets. And “with the growth of cloud services, companies these days might not even be storing their most secret information on their own servers … and even if they are, a lot of this data has gone out over the Internet and come back again,” he says.

That gives corporate spies more and more opportunities and methods to get away with the goods.

So an iPhone 4 walked into a bar …

One particularly high-profile example of smart  trade secret protection was the Apple iPhone4 case. You’ve probably heard about it, and we covered it heavily, too, back in the day. Right before the iPhone4‘s release in 2010, an Apple employee out for an evening of fun accidentally left a prototype of the then-top-secret device on a Silicon Valley bar stool.

trade secret protection was the Apple iPhone4 case. You’ve probably heard about it, and we covered it heavily, too, back in the day. Right before the iPhone4‘s release in 2010, an Apple employee out for an evening of fun accidentally left a prototype of the then-top-secret device on a Silicon Valley bar stool.

Apple managed to regain the lost hardware without too much loss, Pooley explains in his book, thanks largely to the force of trade secret protection. Photos of the device were splashed all over the Internet, but no key details leaked out, and the guy who found the device and took it was forced to do community service after behing charged with misappropriation of lost property, a misdemeanor.

Weirdly, a year later, Apple relived the horror: Again, an Apple employee left a prototype iPhone in a Silicon Valley bar. This time it was the Apple iPhone5 prototype. Once again, trade secret protection helped the company regain its lost device, though not before a leaker shared photos and specs with the media.

Well, shit happens. At least trade secret protection lets you clean up most of the mess.

Because we can’t all hire hordes of Oompa-Loompas …

Remember how, in “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory,” Willy Wonka decided to protect his chocolate recipes against chocolate spies?

Wonka’s solution was to fire all the employees and replace them with hundreds, maybe thousands, of Oompa-Loompas.

Sadly, it’s pretty hard to get hard-working Oompa-Loompas these days. Your best recourse, says Pooley, is to put a serious trade secret protection policy in place at your company.

So think about what pieces of valuable corporate information you need to protect, and how you plan to go about protecti ng it. But it’s important to stay realistic. No matter what you do, the cold, hard fact of it all is that all your employees, even the best ones, are eventually going to slip away. Trade secrets age, too.

ng it. But it’s important to stay realistic. No matter what you do, the cold, hard fact of it all is that all your employees, even the best ones, are eventually going to slip away. Trade secrets age, too.

As Pooley points out, trade secrets typically grow less and less valuable as the products or methodologies they apply to fall out of common use.

The Ashley Madison adultery website hack happened a few days before I interviewed Pooley for this article. It isn’t a trade secret case, but it does illustrate one of the limits of trade secret protection, Pooley said. And that’s the potential inability of trade secret thieves to compensate you.

Now, even if Ashley Madison were able to catch the hackers who snatched the personal data of its wannabe adulterers, how could the firm really ever be compensated for being forced to pause its planned $200 million IPO on the London stock exchange?

Trade secret protection is nonetheless a critical tool for any company with trade secrets, which pretty much means every company.

So should you buy this book?

Yes. Pooley’s book provides an excellent introduction for what you need to know about trade-secret protection now. It’s breezily written and entertaining, so far as a book on trade secrets can be entertaining. And the inclusion of sample documents you can use in building your company’s trade-secret plan is thoughtful and useful.

Yes. Pooley’s book provides an excellent introduction for what you need to know about trade-secret protection now. It’s breezily written and entertaining, so far as a book on trade secrets can be entertaining. And the inclusion of sample documents you can use in building your company’s trade-secret plan is thoughtful and useful.

Secrets, by design, doesn’t veer too deeply into the specifics of any recent trade secret litigations. That really isn’t the point of this book, but if you’re aiming to build a really decent plan to protect yourself against trade-secret theft, you need to be up on what works and what doesn’t in courts and in the court of real life.

So I put some information together for you on a recent, high-profile case that deals with employee raiding. Here are the details on an important trade-secret litigation that just wrapped up, A123 Systems v. Apple. Read about some of the court documents below.

Employee raiding claims in practice: A123 Systems v. Apple

Automotive battery developer A123 Systems sued Apple earlier this year. The litigation tested the strength of A123’s strategy for protecting its human capital and its know-how assets. The case affords a lot of insight on how A123 Systems managed to protect its trade secrets in its battle with Apple, a company many, many times its size.

Remember the hypothetical I started this column with? This case was similar in that a top engineer left A123 Systems for Apple and soon, a bunch of other key employees followed suit.

The battery developer’s suit against Apple centered on five key scientists and engineers who left the firm for Apple and, in the same suit, A123 also sued the engineers individually for violating various clauses in their employment contracts.

All parties reached a settlement just a few months after the case was filed — we don’t know why or in whose advantage, though I suspect it settled in A123’s favor because of the speed with which they reached settlement and Massachusetts’ strong pro-company laws. The point, though, is that the case settled many months before there were any significant decisions on the merits of the case.

In the media, the particulars of this trade-secret case seemed less intriguing than speculation around Apple’s plans to sell electric vehicles. After all, it was hiring teams of tech people from a car-battery maker.

From an intellectual property standpoint, A123’s lawsuit is fascinating because the case tested how various trade protection legal strategies worked for A123 in its fight to protect the brain capital held by key employees that Apple hired away.

For any company willing or able to employ layers of trade secret protection techniques, this case is a great, recent example.

A close examination of the lawsuit also informs one of the sorts of management techniques that could help you avoid such litigations and even reduce the harm inflicted before legal action is taken by your company. Scroll below for the relevant trial documents.

What exactly was A123 complaining about?

The complaint, originally filed in Massachusetts state court and later moved to Massachusetts federal court, included seven causes of action. You can read the full complaint below. They are:

(1) Breach of contract, non-compete covenant; (2) Breach of contract, violation of employee non-solicitation covenant; (3) Breach of contract, violation of non-disclosure covenant; (4) Tortious interference; (5) Unfair competition; (6) Misappropriation of trade secrets and (7) Employee raiding

Legal regimes around the world provide companies with varying degrees of freedom for suing their employees using causes of action such as covenants not to compete.

In some countries and states such clauses are unenforceable even if the employee has signed the contract. But Massachusetts, the U.S. state in which the employees worked, provides somewhat more employer-friendly rules than other jurisdictions, such as California where such clauses are unenforceable.

These engineers all worked in A123’s Waltham, Mass. research facility, in which it was developing Lithium-ion batteries. According to the docs, one of the defendants ran the Waltham facility and was in charge of the Lithium-Ion division. And this complaint from A123 suggests that this particular employee helped Apple select which employees to recruit into Apple’s new battery program.

The raiding cause of action is somewhat unique to this litigation, as complaints against employee raiding would typically be handled by the other complaints aimed against Apple.

In its complaint, A123 claims that Apple had also poached battery scientists from LG, Samsung, Panasonic, Toshiba and Johnson Controls. So far, though, none of these parties have sued Apple.

The complaint also named as defendants five former A123 employees. The three breach of contract claims are leveled against them. The NDAs that these employees signed were likely very helpful to the overall case. Too many small companies don’t NDA their employees adequately. The A123 case is a good reminder for why you definitely want to make sure you’re not one of them.

In short, A123’s trade secret protection plan was sterling in that it really did everything it could do early on so that, if it needed to, it had all the legal weapons it would ever need to fight anyone. Even giant Apple.

For court documents and other key information regarding the A123 Systems v. Apple case, scroll below the fold.

The A123 v. Apple complaint:

Employment agreements and correspondence between A123 and Apple:

More correspondence between A123 and Apple:

For aNewDomain, I’m Tom Ewing.

Photo Credits:

Cover: World War II secrets poster courtesy Wikimedia Commons, This work is in the public domain in the United States because it is a work prepared by an officer or employee of the United States Government as part of that person’s official duties under the terms of Title 17, Chapter 1, Section 105 of the U.S. Code; Das Geheimnis – Le Secret, “Das Geheimnis – Le secret“ by Felix Nussbaum – http://www.felix-nussbaum.de. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons; James Pooley, courtesy Veruspress, All Rights Reserved; book cover for “Secrets – Managing Information Assets in the Age of Cyberespionage, courtesy Veruspress, All Rights Reserved; Oompa-Loompas, courtesy The Telegraph, all rights reserved; Bran castle secret passage,”Bran castel secret passage” by Alessio Damato – Own work (I took this picture by myself). Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons. See Copyright; Ashley Madison company logo, “Ashley Madison logo” by Source (WP:NFCC#4). Licensed under Fair use via Wikipedia.