aNewDomain — Multinational companies like Google, Facebook, Starbucks and Amazon pay less tax in Austria than a sausage stand in that country, complains Austrian chancellor Christian Kern.

“Every Viennese cafe, every sausage stand pays more tax in Austria than a multinational corporation,” Kern added.

Kern isn’t alone in his outrage. This summer, the European Union hit Apple with a 14.6 billion dollar tax bill, claiming that a dodgy transfer pricing tax arrangement it had with Ireland enabled it to dodge those taxes.

Apple CEO Tim Cook called the bill “total political crap” and defended its tax relationship with Ireland, but no one can deny the fact that corporate tax rules differ widely from country to country, a difference that makes tax havens possible for the world’s wealthiest corporations.

Every year multinational companies dodge between $100 and $240 billion in tax due to the world’s inconsistent corporate tax rules, according to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), a 35-member intergovernmental economic organization that held its latest round of hearings on the matter last week in Paris.

Put another way, the amount of tax dodged is somewhere between the entire annual economic output of Kuwait or Israel or nearly 15,000 brand new American schools.

For multinational companies in general, and Silicon Valley tech behemoths in particular, there is a lot at stake here.

Once approved by member governments, the OECD regulations could put an end to the corporate tax department as a profit center, said the tax project’s director, Pascal Saint-Amans.

The OECD aims to reduce if not eliminate the advantages of transfer pricing, he added.

The new tax rules would cost corporations, no question, but they’ll bring lots of cash to governments. In the absence of collecting these taxes, governments must either cut programs, raises taxes for other folks and/or increase their debt limits, but the new tax rules would create a windfall that enables them to collect billions in taxes that currently is slipping through the net.

No one has calculated how much of the world’s governmental debt can be laid at the door of transfer pricing, he said.

The move to level the playing field and get rid of corporate tax dodge techniques is a direct result of the 2008 financial crisis; all 35 members of the OECD are now willing to share tax data with each other and to work together to close loopholes.

Saint-Amans explained that the new program aims to eliminate both double taxation and double non-taxation, both of which cause revenue collection problems for governments worldwide.

Stories are supposed to be about good guys and bad guys. This simplistic meme doesn’t fit transfer pricing and base erosion and profit shifting. If the world’s tax rules allow Bloato Co., a multinational company, to park assets used heavily in the United States in say low tax Kleptostan, and Bloato Co. pays its share of taxes based on this arrangement, then Bloato Co. hasn’t violated existing laws or cheated anyone.

In fact, if Bloato Co.’s executives owe their first duty to their shareholders, then not taking advantage of transfer pricing is arguably violating a duty to increase shareholder value. Basically, the US has just been stupid for allowing Bloato Co. to allocate its profits this way.

Saint-Amans explained that the basic principal behind the complicated new tax scheme is: arm-length transactions looked at in reality rather than what can be shown on paper. So, for example, if a company parks legal ownership of all its intellectual property assets in a low-tax country for IP assets, then the company needs to explain how parts of the company negotiated arms-length licenses for these IP assets in other parts of the world.

Meanwhile, multinationals scramble

The new OECD rules apply to more than just intellectual property assets, but the OECD rules have made a special effort to look at the treatment of intellectual property assets – patents, copyrights, trademarks, trade secrets, and know how, as companies often park these assets in countries where they are not taxed or lightly taxed.

To properly account for their intellectual property assets under the new OECD rules, many companies will need more formal procedures for documenting inter-company agreements and inventorying their intellectual property assets. This will require a level of rigor that many companies have not previously employed.

The new OECD rules highlight the importance of intellectual property management systems. Tech companies may need to acquire fairly sophisticated systems for inventorying all their IP assets, well as systems for recording the metadata related to these IP assets, such as inter-company agreements.

Saint-Amans explained that the OECD does not like “patent box” schemes but that the new rules will sanitize patent box schemes for the countries that choose to implement them. Patent box tax schemes are ones that allow companies to lower their corporate tax burdens by exploiting a patent. The UK, for example, started a patent box tax scheme in response to the economic downturn of 2008. The new OECD rules will allow patent box under some circumstances, said Saint-Amans, but there must be a closer nexus between the patent and profits than has been the case with most laws, he said.

Here is an example of some of the tax implications of IP assets from the materials prepared by the OECD:

In Year 1, a multinational group comprised of Company A (a country A corporation) and Company B (a country B corporation) decides to develop an intangible, which is anticipated to be highly profitable based on Company B’s existing intangibles, its track record and its experienced research and development staff. The intangible is expected to take five years to develop before possible commercial exploitation. If successfully developed, the intangible is anticipated to have value for ten years after initial exploitation. Under the development agreement between Company A and Company B, Company B will perform and control all activities related to the development, enhancement, maintenance, protection and exploitation of the intangible. Company A will provide all funding associated with the development of the intangible (the development costs are anticipated to be USD 100 million per year for five years), and will become the legal owner of the intangible. Once developed, the intangible is anticipated to result in profits of USD 550 million per year (years 6 to 15). Company B will license the intangible from Company A and make contingent payments to Company A for the right to use the intangible, based on returns of purportedly comparable licensees. After the projected contingent payments, Company B will be left with an anticipated return of USD 200 million per year from selling products based on the intangible.

A functional analysis by the country B tax administration of the arrangement assesses the functions performed, assets used and contributed, and risks assumed by Company A and by Company B. The analysis through which the actual transaction is delineated concludes that although Company A is the legal owner of the intangibles, its contribution to the arrangement is solely the provision of funding for the development of an intangible. This analysis shows that Company A contractually assumes the financial risk, has the financial capacity to assume that risk, and exercises control over that risk in accordance with the principles outlined in paragraphs 6.63 and 6.64 (of the OECD’s report). Taking into account Company A’s contributions, as well as the realistic alternatives of Company A and Company B, it is determined that Company A’s anticipated remuneration should be a risk-adjusted return on its funding commitment. Assume that this is determined to be USD 110 million per year (for Years 6 to 15), which equates to an 11% risk-adjusted anticipated financial return. Company B, accordingly, would be entitled to all remaining anticipated income after accounting for Company A’s anticipated return, or USD 440 million per year (USD 550 million minus USD 110 million), rather than USD 200 million per year as claimed by the taxpayer. (Based on the detailed functional analysis and application of the most appropriate method, the taxpayer incorrectly chose Company B as the tested party rather than Company A.

The OECD’s introductory press conference for its adjustments to transfer pricing and base erosion and profit sharing:

Here are videos from the OECD’s hearings in Paris last week. If you have trouble viewing them in place in your browser, click to view it fullscreen.

The first session on Oct. 11:

The second OECD session on Oct. 11:

The third session on Oct. 12:

The fourth session on Oct. 12:

The OECD has produced numerous documents related to its efforts to curtail abuses in transfer pricing and base erosion and profit shifting. Here is the document for Actions 8-10: Aligning Transfer Pricing Outcomes with Value Creation:

[scribd id=327772981 key=key-PsWceWnzZXj6N3n4VcaE mode=scroll]

Here is the OECD’s document for Transfer Pricing Documentation and Country-by-Country Reporting, Action 13 – 2015 Final Report

[scribd id=327773988 key=key-Hur91rImPalP5Wx8rO7s mode=scroll]

For aNewDomain, I’m Tom Ewing.

Credits:

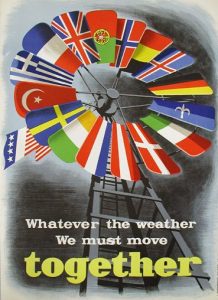

Cover art: Marshall Plan OECD poster: Selfish Shellfish At PixelACHE (2005) Finland by CC BY-SA 3.0, All Rights Reserved. Cover image: by E. Spreckmeester (also credited as “I. Spreekmeester”), via WC, All Rights Reserved.