The following is an excerpt of Brian Blum’s new book, Totaled: The Billion-Dollar Crash of the Startup that Took On Big Auto, Big Oil and the World.

aNewDomain  — If the charge spots were the day-to-day charging apparatus for Better Place’s customers, the battery switch stations were the “backup system,” a psychological boost that enabled drivers to push past “range anxiety”—to feel they could travel unlimited distances in their electric cars because they could always swap batteries if they were running low—even if, in general practice, 90 percent of charging would be done at home or at work.

— If the charge spots were the day-to-day charging apparatus for Better Place’s customers, the battery switch stations were the “backup system,” a psychological boost that enabled drivers to push past “range anxiety”—to feel they could travel unlimited distances in their electric cars because they could always swap batteries if they were running low—even if, in general practice, 90 percent of charging would be done at home or at work.

The switch stations were to become the public face of the company. And why not? They were sexy and oh so futuristic: a network of filling stations run entirely by robots.

Better Place CEO Shai Agassi preferred another metaphor.

“Ever been to a carwash?” he asked, while on stage during an appearance at the NDN think tank’s “Moment of Transportation” conference in Washington, D.C., in March 2008.

[mks_pullquote align=”right” width=”388″ size=”24″ bg_color=”#000000″ txt_color=”#ffffff”]

Danny Weinstock was a big fan of fast charge, where you stop and plug in for 40 minutes and get an 80 percent charge. Like the battery switch station, it was a psychological trick that allowed drivers to feel they wouldn’t get stranded, even though they would rarely use it.

“Shai always considered himself an average person, and if he wouldn’t wait, no one would,” Weinstock said. “I told him, you’re not average. Other people aren’t flying 200,000 miles a year. Not everyone is as busy as you. So what if a driver has to wait while the car is charging? Give him a croissant. It’s a marketing issue.”

[/mks_pullquote]

A carwash has lots of moving arms. Now, if I wanted to scare you, we’d call them robots. They move in all kinds of directions, they have shampoo, they have wax. Stuff is coming in. A battery switch station, on the other hand, has only one arm. It only goes up and down. It comes underneath your car, like you’re sitting in a carwash. The empty battery goes out and a full battery goes in.”

Better Place’s battery switch stations would be a wonder of automation.

As the car approaches, the station identifies it through a cellular connection to Better Place’s central Network Operating System, a room filled with enormous screens and technicians hunched over computer terminals, resembling the iconic Mission Control Center of the NASA moon launches.

After the identification is complete, a swinging gate at the entrance to the switch station automatically opens. Large, color LCD signs guide the driver to pull the car up to a stopping point, then to switch the vehicle into neutral and turn off the engine.

Hydraulic clamps grab the car and move it slowly forward while the platform rises slightly. It’s all very graceful. While the driver must stay with the car, passengers can get out and watch the process from a glassed-in observation deck.

Once the car is in exactly the right spot, a mechanism gives the underside of the car a quick wash, to avoid dirt contaminating the battery and to make sure none of the parts have gotten rusty.

At this point the real magic begins.

Beneath the back half of the car, a secret door slides open, revealing a deep well.

The first robot sidles up to the car from the right, rises up and twists open four screws. The car’s 500-pound battery drops slightly from its location between the rear passenger seat and the trunk onto the robot’s sturdy serving tray. The battery is then whisked into the bowels of the station, where up to 16 other batteries are being cooled to ensure that, when they’re charged under these optimal conditions, any degradation will be kept to the absolute minimum.

On the other side of the observation deck, a window allows drivers to peer down several stories into the ground, where the interior of the station is laid out like a giant jukebox—except one filled with batteries, not vinyl records.

The spent battery goes into one bay, while a second robot plucks a fresh battery from its resting spot and sends it along a conveyer belt until it is ready to be inserted into the car. Up it goes, jiggling gently until snugly in place. The screws are returned, the hidden well is sealed and the car is lowered back to ground level.

Once the clamps are released, the LCD screen, which has been providing progress reports the entire time, changes to green, indicating it’s time to put the car back in drive and head on your way.

The biggest difference between a battery swap and a carwash: If you stay with your car, you can’t listen to the radio. After all, during the switch, your car has no battery!

Better Place’s switch stations would be fast, Agassi predicted—faster than a carwash and certainly faster than plugging your car into the charge spot on the wall.

“We’re not dealing with electrons moving in and out, we’re dealing with mechanics moving in and out,” he told the NDN audience.

The first switch station to be prototyped took one minute and 13 seconds to swap a battery.

“If we can’t do this in less time than it takes to fill your gasoline tank,” Agassi told New York Times reporter Clive Thompson, “we don’t have a company.”

Agassi went farther in his NDN talk, calling the Better Place system a “social contract.”

“Technologists will tell you that, until you have a battery that charges up three hundred miles in three minutes or less, like you can do with gas, people won’t buy it,” he explained. “We think the social contract is a bit different. We think people are not going to be willing to stop more than fifty

times a year for more than five minutes [for a fill-up]. So if you can guarantee me [I’ll have to stop] less than 50 times a year—less than my current once a week fill-up model—and guarantee that it won’t take more than five minutes, I’m good. We do that; we guarantee that in our contract.”

Moreover, how often do you drive more than 100 miles non-stop? Agassi mused. “So we’re actually giving you a better contract. You’ll stop less than 50 times a year, because most of the time, you drive to work and an hour later it will be topped off magically.”

Better Place built its first battery switch station not at home in Israel or in the United States, but in faraway Japan.

Better Place won a government competition sponsored by the Japanese Ministry of the Environment to build a prototype battery switch station in Yokohama, an hour’s drive from Tokyo.

The Japanese government wanted to prove that electric cars were viable and had set a goal of having electric-powered cars account for 50 percent of the cars sold in Japan by 2020.

Nissan was pressing forward with the Leaf, which would, seven years later, become the best-selling 100 percent electric vehicle in the world. There were others, too: Subaru had a car called the Stella and Mitsubishi was pushing the i-MiEV.

But that old gremlin, range anxiety, was damping down sales. The Japanese were asking for innovative ideas on how electric cars could travel farther.

The first thing to build was the car itself, because the existing electric vehicle models in Japan were not switchable.

So Quin Garcia, who had cobbled together the first electric prototype in Israel just a few months earlier, was dispatched to the Land of the Rising Sun to work his magic again.

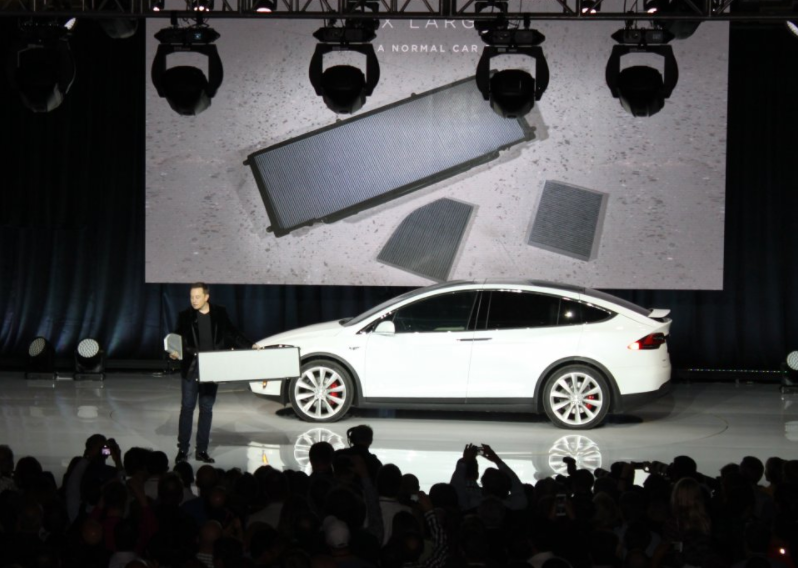

The vehicle chosen for the trial was a Nissan Qashqai, a crossover SUV. Garcia opted for what’s called a “pancake” battery, mounted on the bottom of the car, rather than in the trunk as the Renault design would be. The pancake design is what most electric vehicles – including the Tesla – use today.

“It’s much easier from an engineering perspective,” Garcia said. “You just push it up into the bottom of the car. You don’t have to line it up perfectly in a long deep cavern, as in a trunk-mounted design.”

Garcia and Better Place chief engineer Yoav Heichal traveled back and forth to Japan every two months until the station opened, a year later, on May 13, 2009.

A white Nissan Qashqai with the words Better Place written across its rear left (a small blue Better Place logo balanced the text from the right) drove onto the grounds of the switch station, with its white canvas roof.

The Qashqai circled around the back before entering the station to roll on top of the charging platform, which was raised so audience members assembled for the demo could see what was happening underneath, before the Qashqai continued on its way.

For good measure, photovoltaic solar panels provided by Japanese manufacturer Sharp were positioned across the top of the switch stations, “creating a truly zero-emission solution,” according to a Better Place press release.

Better Place had invited an international coterie of reporters and automotive bloggers to the event. The Danish and Israeli ambassadors to Japan were there, as were most of Better Place’s key executives. The entire event was webcast live.

Not everyone within Better Place backed the battery switch station concept, though.

Danny Weinstock should have been a believer—it was his job as charging grid manager—but looking back, he admitted the company’s tireless focus on switch “never made sense” to him.

Weinstock, who previously worked at the Israeli Energy Ministry, was concerned about the high cost of maintenance.

“When you come from low-tech like me,” he said, “everyone knows that if you have something that’s moving, there’s going to be costs involved for maintenance. But Better Place never took that into account. There were all these moving parts that needed to be very accurate, with optical sensors and the like.”

Car manufacturers are conservative, Weinstock warned. “Shai thought he could change the whole industry, to force everyone to take the battery in and out. But it was against their nature.”

Car manufacturers are conservative, Weinstock warned. “Shai thought he could change the whole industry, to force everyone to take the battery in and out. But it was against their nature.”

Shmuel Harlap felt Better Place’s solution was actually moving backwards.

They’re setting up “the world’s biggest puncture repair shop,” said Harlap, who is the chairman of Israeli Mercedes importer Colmobile. He likened it to the battery-switch process to that of fixing a flat tire by swapping in a new one rather than by making a better, puncture-proof tire.

“It’s a solution that belongs in the nineteenth century,” he said disdainfully.

Sue Cischke, group vice president for sustainability, environment and safety engineering at Ford, was doubtful Better Place could convince all carmakers to agree to design their cars around one standard-size battery bay.

“The chemistry is still changing, and it’s still a developing technology rather than a mature technology,” she told The New York Times. Given that cars can take years to design, making the wrong call on a standardized battery could be economically fatal for a carmaker, she added.

Better Place’s head of automotive alliances Sidney Goodman said he wasn’t worried.

Even though there would one day be many different makes and models of electric cars on the road, they’d use batteries from a relatively small number of manufacturers, Goodman explained to Wired at the time.

Others weren’t convinced.

Bill Reinert, national manager for Toyota Motor Sales’ Advanced Technology Vehicle Group, pointed out that “an electric vehicle battery pack needs to be weather-tight to keep water out, and … battery pack seals are not traditionally designed to be taken on and off all the time.”

Ford’s Cischke was worried that if there was an issue with the battery exchange, and the consumer has a bad experience, “then they will blame Ford, not necessarily Better Place.”

What could Better Place have done instead?

Danny Weinstock was a big fan of fast charge, where you stop and plug in for 40 minutes and get an 80 percent charge. Like the battery switch station, it was a psychological trick that allowed drivers to feel they wouldn’t get stranded, even though they would rarely use it.

“Shai always considered himself an average person, and if he wouldn’t wait, no one would,” Weinstock said. “I told him, you’re not average. Other people aren’t flying 200,000 miles a year. Not everyone is as busy as you. So what if a driver has to wait while the car is charging? Give him a croissant. It’s a marketing issue.”

Sue Cischke admitted that Better Place had “really energized people with thinking outside the box. But I don’t think that’s the answer that we’re looking at.”

In many ways, the debate was reminiscent of the Betamax vs. VHS wars of the 1980s. Even though Sony’s Betamax was arguably the superior video technology, consumers chose VHS—and Betamax tapes have been relegated to a footnote in a tech museum.

Would that be the fate of battery switch as well?

For aNewDomain, I’m Brian Blum.

Here’s Better Place CEO Agassi’s TED Talk from 2009.

Image credits: Christian Science Monitor, All Rights Reserved; EcoProfit.Ro, All Rights Reserved; BusinessInsider.SG, All Rights Reserved; GreenProphet.com, All Rights Reserved.