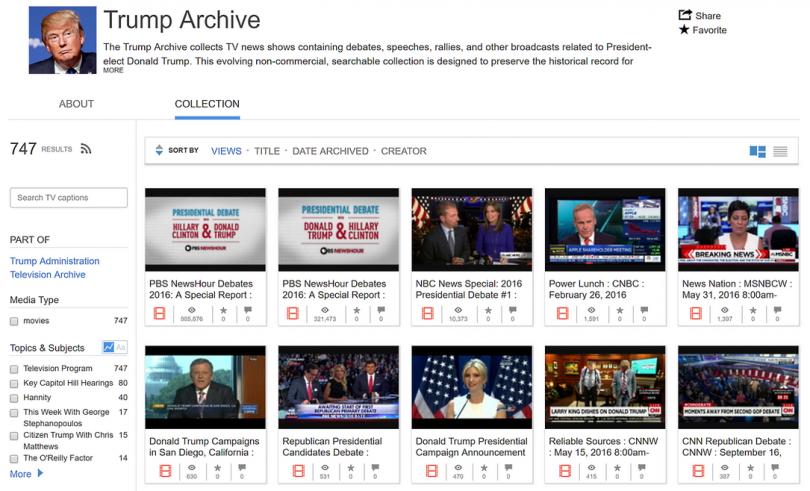

aNewDomain — I watched with great interest this week as the Internet Archive launched its newest collection, The Trump Archive.

The point of the Trump Archive, said organizers, is to hold the incoming US president responsible for his ever-changing pledges and contradictory statements — and to preserve, to the degree that it’s possible, a truthful historical record for future generations.

“Reporters, researchers, Wikipedians, and the general public are invited to quote, compare and contrast televised statements made by Trump,” Internet Archive managing editor Nancy Watzman said in a blogpost.

“Reporters, researchers, Wikipedians, and the general public are invited to quote, compare and contrast televised statements made by Trump,” Internet Archive managing editor Nancy Watzman said in a blogpost.

“We hope to provide assistance for those tracking Trump’s evolving statements on public policy issues. For example, in July 2016 Trump told ABC’s George Stephanopoulos, ‘I have no relationship with Putin.’

“But Politifact,” Watzman continued, “ruled this statement by Trump as a ‘full flip flop’ (because) … it contradicted what he had said on multiple previous occasions.”

True.

Trump’s comments to Stephanopoulos contradicted comments he made to MSNBC ‘s Thomas Roberts in November 2013, when he said “I do have a relationship” with him, or to an audience at a March 2014 CPAC conference when he bragged that “Putin … sent me a present, a beautiful present.”

To a National Press Club audience in May 2014, he said that in Moscow, he’d spoken “indirectly and directly with President Putin.” And in a Nov. 15, 2015 Fox Business News debate, Trump said “I got to know him very well because were were both on 60 minutes .. we were stablemates, and we did very well that night.”

Enter the Trump Archive

“By providing a free and enduring source for TV news broadcasts of Trump’s statements,” Watzman said, “the Internet Archive hopes to make it more efficient for the media, researchers, and the public to track Trump’s statements while fact-checking and reporting on the new administration.”

Can the Internet Archive, a public foundation that has strived to provide “universal access to all knowledge” with its 15 petabyte digital archive and associated Wayback Machine web archive for two decades now, keep Trump honest?

It sure can try.

In the beginning, we were so naive

<

div class=”post-body”>

My optimism in the early days of the internet was for sure naive. And I wasn’t alone.

My optimism in the early days of the internet was for sure naive. And I wasn’t alone.

Most of us back then believed the new medium would both enhance democracy and produce mounds of valuable, objective data for historians, too.

Remember the Soviet coup attempt of 1991? At the time, I was working on a team to create an archive of the network traffic going in and coming out of the Soviet Union and also within it.

The traffic flowed through a computer called “Kremvax,” operated by RELCOM, a Russian software company.

The content of that archive wasn’t government or media-generated. It was true citizen journalism, the collective work of independent observers and participants working through a university and storing at a server there.

It was as objective as we could possibly make it.

It was as objective as we could possibly make it.

What could go wrong?

What fed my optimism was the advent of the Web and, then, services like Wikipedia.

For example, when terrorists attacked various locations in Mumbai, India in 2008, citizen journalists inside and outside the hotels that were under attack began posting accounts.

The Wikipedia topic began with two sentences: “The 28 November 2008 Mumbai terrorist attacks were a series of attacks by terrorists in Mumbai, India. Twenty-five are injured and two killed.”

In fewer than 22 hours, 242 people had edited the page 942 times expanding it to 4,780 words organized into six major headings with five subheadings. (Today it is over 130,000 bytes, revisions continue and it is still viewed more than 2,000 times per month).

The Arab Spring protests in 2010 were also seen as a demonstration of the power of the internet as a democratic tool and repository of history.

Eventually, though, or maybe inevitably, the internet turned out to be a tool of governments and terrorists as well as citizens. Furthermore, historical archives can disappear or, worse yet, be changed to reflect the view of the “winner.”

Our Soviet Coup archive was set up on a server at The State University of New York at Oswego, by Prof.  Dave Bozack.

Dave Bozack.

But what if he retires? What if someone deletes it?.

On Wikipedia, for example, if someone tries to delete or significantly alter the page on the Mumbai attack, he or she will probably be thwarted by one of the volunteers who has signed up to be “page watchers.” Such people are notified whenever the page they are watching is edited.

And it gave everyone hope, as Jon Udell described in this podcast, that Wikipedia vandalism on that page was rapidly corrected.

But does that scale?

Volunteers burn out over time. The page on the Mumbai attacks has 358 page watchers, but only 32 visited the page after its most recent edits.

And, even if a Wikipedia page remains intact, links to references and supporting material will eventually break. That’s what’s known as link rot.

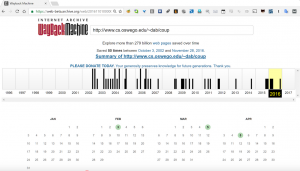

So, if our Soviet Coup archive disappears after Dave’s retirement, all links to it will break.

Now, by the time of the Arab Spring protests, most early internet observers were aware of how naive they’d been at the start of it all. By then, cyberwarring governments and terrorists alike were already using it for their own ends.

That’s when, for most of us, any hopes and dreams we had about the internet being a medium that would ensure the delivery of raw, objective historical data began to fade.

Early visions

I was slow to understand the fragility of the internet. But other observers, like Internet Archive founder Brewster Kahle for instance, picked up on that fact early.

In 1996, Kahle established the Internet Archive for the purpose of preserving a cache of web pages as they existed at various points of time, which he hoped would preserve them against deletion or modification.

In their two decades of existence, Kayle’s Internet Archive has amassed a massive online repository of books, music, software, educational material, and, of course, web sites, including our Soviet Coup archive. (As shown here, it has been archived 50 times since October 3, 2002 and it will be online long after Dave retires — as long as the Internet Archive is online, anyway.)

Kale understands that saving static Web sites like the Soviet Coup archive only captures part of what is happening online today. Since the late 1990s, we have been able to add programs to Web sites, turning them into interactive services.

That’s why the organization’s recent project to archive virtual machine versions of interactive government services and databases is so critical.

Understandably, Kahle is especially concerned by the election of Donald Trump, who has demonstrated a keen ability to exploit the internet and a disregard for truth.

And so he is raising money to create a backup copy of the Interent Archive in Canada and working to archive US government sites and services, too.

But the internet is inconceivably large and growing exponentially.

And there is no way the Internet Archive can capture it all.

The Internet Archive may be the world’s leading internet preservation organization, but this is nonetheless a massive challenge.

Khale and his staff will continue their work and will inspire and collaborate with other relatively specialized efforts like that of climate scientists who are working to preserve government climate-science research results, data and services.

As for the Internet Archive’s Trump Archive, it so far features 700 plus televised speeches, interviews, debates and other news broadcasts. Mention by a fact-checking site was the signal used for inclusion of a video and links to the fact-check document are included in a companion spreadsheet.

I hope they use speech recognition to produce searchable transcripts, too.

I also hope we will have similar, timely archives in the future. One can even imagine similar archives for state and local campaigns if a crowd-sourcing system were developed.

It may be the only hope we have.

Too bad we didn’t have Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton archives during the campaign.

For aNewDomain, I’m Larry Press.

<

div class=”separator”>

For more on the Internet Archive, check out this recent PBS News Hour segment.

You can read the transcript here.

I’d also recommend listening to this short (5m 14s) podcast interview of Brewster Kahle.

In it, Kayle describes the End of Term project, a collaborative effort to record US government (.gov and .mil) Web sites and services when a new administration takes over. He describes deletions and modifications from 2008 and 2012 and feels a special urgency today — for obvious reasons.

Read a transcript of the interview here.

Cover image: The Internet Archive, All Rights Reserved. Inside images: Kremax image: Larry Press, All Rights Reserved; Mumbai terrorist attack image from 2008, Brittannica.com, All Rights Reserved.

<

p style=”text-align: center;”>An earlier version of this article ran on Larry Press’ CIS471 blog. Read it here. -Ed