aNewDomain — The other day, a friend asked me if I thought today’s computers would ever be truly capable of artificial intelligence.

aNewDomain — The other day, a friend asked me if I thought today’s computers would ever be truly capable of artificial intelligence.

It depends, I told him. How do you define intelligence?

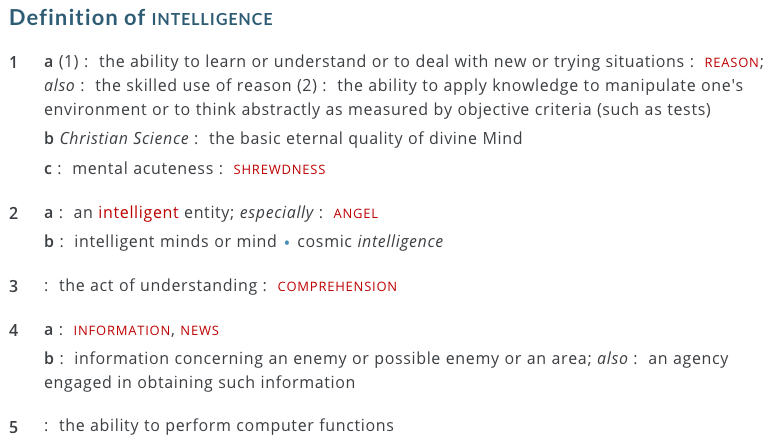

Webster’s primary definition of intelligence is “the ability to learn or understand or to deal with new or trying situations.” In other words: Adaptibility. Flexibility.

Now, by this definition AI is already there, I told him. Look at the Google car: It already has the ability to adapt to changing circumstances: traffic, detours, pedestrians.

And the autonomous Google car is designed to even learn on its own — just by observing outcomes based on decisions it or other Google cars have made. It’ll share those discoveries with other AI enabled cars and systems, which will in turn build on that knowledge …you get the idea.

And the autonomous Google car is designed to even learn on its own — just by observing outcomes based on decisions it or other Google cars have made. It’ll share those discoveries with other AI enabled cars and systems, which will in turn build on that knowledge …you get the idea.

So yes, I told him. We’re there. Mission accomplished.

This was disingenuous of me, you know. Because I knew from the start that he was asking the wrong question from the start. It wasn’t what he really wanted to know. What he really wanted to know — what most people want to know — is when do I think computers will be able to think, reason, perceive and relate as well as humans or better. When will they be sentient?

That’s a totally different question.

To address that one, I’d have to take him back all the way to 1950, when computing pioneer Alan Turing came up with that broadest way of testing computer intelligence, The Turing Test. Tech readers of this publication for sure know Turing and how he came about the now famous computer intelligence test that bears his name.

Passing the Turing test is a straightforward challenge. A computer just has to trick a human in a double-blind test that it also is a human. And it has to do it solely through a natural language conversation. As Turing wrote it, a computer only needs to fool its human judge at least 70 percent of the time. Then it can be said to exhibit intelligent behavior.

But having a computer that’s a champ at such foolery doesn’t mean it’s sentient. (And it’s worth noting that while only a few AI systems have passed the Turing test, plenty of computers out there are way smarter than the one Turing test winning system rumored to have threatened its humans with the idea of a “people zoo.”)

This is why the Turing test is not too low a bar, as some have claimed. It’s too high a bar.

This is why the Turing test is not too low a bar, as some have claimed. It’s too high a bar.

There are plenty of intelligent AI systems out there already that would fail that test, but are sufficiently advanced to trick you in other, more important ways.

Make it till you fake it

With his test, you know, Turing is avoiding the whole notion of whether a computer can think. The test is merely to establish whether a given computer imitate a human and fool another human by miming what a human might be like.

That is advanced enough.

But a computer that is as good or better at humans at some task or category of tasks is definitely a smart one, Turing be damned.

Don’t believe me?

Say you were blindfolded and placed in the back of a self-driving car. Would you assume you were being driven by a robot if no one said otherwise? The car can successfully imitate a human driver, albeit one that observes all traffic laws. In fact, tests have shown it is actually a safer driver, too.

This is what bothers me about the whole line of questioning around future sentient computers and how we’ll recognize them. It’s unproductive. It’s also ridiculously vague.

To have this conversation about the future of computing or the value of the intelligent systems cropping up around us right now, we need to know what we mean by words like ‘intelligence,’ ‘better’ and even sentient.

If it is the ability to fool a human into thinking the computer is a human then I am at once sad and happy to say we are very nearly there. Sad because it’s not that hard to fool us humans — and happy because, well, we did it. That’s a pretty big deal, considering how far we’ve come in just the last 10 years, much less since 1950 when Turing devised his test.

Riddle me this

Once we can define just what we mean by intelligence, sentience, all of it, we should move on to the larger question. And that is: What happens when (not if) we develop a program that can learn, reason, deduce and infer in a way that equals or rivals human thinking?

And while you can envision a scary, Singularity type uber-machine running everything and maybe even plotting our demise, it’s better not to if you really are a technologist coming up with better, smarter technologies and deep learning systems that will benefit mankind — and which ones we can imagine right now that definitely, most assuredly won’t.

Perhaps focus your question on the military.

What will happen when an AI military system seems to be so much better than humans at predicting disasters and reacting to them that humans gradually cede their veto seat at the table. Ever heard of the Russian who saved the world from nuclear war in the 1980s. It was all because he didn’t trust the computer that erroneously told him US nukes were on the way.

In the future, will such a save be possible? Will humans stupidly pull themselves out of the decision loop? I can tell you that that’s what keeps lots of AI and robotics ethicists awake at night.

Or focus on medicine. Just recently, AI systems have made huge strides. Especially when it comes to computer vision, which really is just the ability to recognize and interpret images. Just last week, Google Brain chief Jeff Dean told my colleague Gina Smith that he never could’ve predicted how fast or how good computer vision has become. In medicine especially, Dean said, there are lots of examples now where deep learning algorithms aren’t just as good as humans, but better.

When that’s the case in vertical after vertical, what then?

This is a good question to ask. Why? Because we know that future is coming. Some people want to know who will watch the people who watch the machines watching the people? That’s a good thing to wonder.

Others pontificate about whether Asimov’s Rules for robots should be programmed into all computers. That sounds like a good question, and maybe it is, but the answer is: No. Those rules didn’t even work in fiction, which is why Isaac Asimov created them. They’re straw men, just literary devices. And please. How are you going to program a rule like “never harm humans” into an autonomous weapon that’s programmed to kill as many as possible, as efficiently as possible.

Questions of computer and AI ethics do loom large, and people are wrestling with these issues as I write. They are good questions. And they are the right ones, too.

It won’t be long before asking a computer what the meaning of life is — and hoping for a 42 — doesn’t seem the least bit clever anymore. It’ll be cornpone, a question from yesteryear for historians and trivia nuts. But so it goes.

For aNewDomain in New York, I’m Jim McNiel.

Cover image by Bruce Rolff, Shutterstock.com, via Banknxt: All Rights Reserved.