Image credit: Madison Andrews

aNewDomain.net — Using Google Play for Education’s wireless distribution model, schools potentially spend far less on in-house technical support and maintenance. And that’s good news. But those savings pale in comparison to the up-front cost of Google’s mobile hardware. And that’s just one of the issues to consider when looking at the upside — and the downside — of mobile tech in schools.

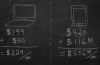

First consider. Wi-Fi-enabled Acer C7 Chromebooks cost $229 each for schools and educators in the United States. That’s $199 for the Chromebook and $30 for management and support.

Despite the reduced price, Chromebooks are still an expensive luxury for cash-strapped schools. Yet some U.S. districts have already paid much more for Apple iPads.

Take the San Diego Unified School District. It spent upwards of $2.8 million in capital appreciation bonds to invest in more than 21,500 Apple iPads and nearly 77,800 laptops last year. SDUSD bought its Apple iPads in two phases: For the first 10,729, it used a series of 40-year bonds. Each tablet cost $420, plus $116.50 for three-year warranties and accessories.

But, after reviewing the bond documents, the Voice of San Diego concluded that the district will pay roughly 7.6 times that amount in total — or $4,077 per iPad.

The second phase will be less burdensome, with similar per-device calculations amounting to $2,731.

That’s still some incredibly expensive hardware to put in the hands of students. The whole rigamarole incited serious outrage from San Diego’s County Taxpayers Association. But the district stands by its decision, citing projected improvements in their students’ educational experience as justification for the exorbitant costs.

But exactly how do devices like the iPad and Chromebook really improve the educational experience? And if so, to what degree?

The jury’s still out on these questions, at least in terms quantifiable results.

Even if schools do report higher scores after an infusion of pricey gadgets, how would they go about asserting a causal link between technology and student performance?

Any number of factors could contribute to those results, including — and perhaps most importantly — how teachers actually use the tools on a daily basis. In the hands of an unenthused or uninformed educator, new technology would make little difference.

Jennifer Carey said it well on the Powerful Learning Practice blog:

Simply handing out iPads to teachers and students (and going over the security protocols) isn’t going to accelerate learning in your school. Educators need to become skillful at using these tools and then think deeply about how to integrate them into the learning environment in powerful ways.”

Mobile technology provides endless possibilities.

But at the end of the day, it’s up to individual teachers to go home and re-imagine their classrooms in the light of a new device. Would Great Expectations by Charles Dickens be more engaging if students could leave comments on a classroom-wide e-book?

Are cell structures easier to memorize in the form of an interactive chart?

Could a YouTube video help students with their algebra homework, and ease the burden on parents who can’t remember how to solve for x?

My point is that technology — whatever the price or the logo attached — is not a panacea in and of itself.

At best, mobile devices and software are highly functional platforms for curricula, which can greatly enhance learning if implemented in thoughtful, creative ways. At worst, they are a huge waste of money for districts and taxpayers.

To put it another way, a pneumonic device may have helped me learn the quadratic formula in middle school. But it was my algebra teacher who really made it stick. Day after day, she led the class in a rousing chorus of variable recitation.

Years later, I rely on my iPhone for the simplest of calculations. But I can still sing that formula by heart.

Can an app do that?

Maybe.

But it still takes the dedication of individual teachers and the support of thoughtful administrators, to get an entire classroom of students excited about learning math.

Neither Apple nor Google is likely to care as much about the efficacy of technology as educators do.

The bottom line will always be more important. In the education market, that line includes not only selling products to schools, but seeding future generations of users. Apple has always been unique in its ability to capture the imaginations of young people.

But Google is out of its league in terms of such open-ended marketing expertise.

For aNewDomain.net, I’m Madison Andrews.

Madison Andrews is a journalist and graphic designer based in Austin, Texas. She is also the blogger and designer behind Mad Skills Vocabulary, a writing and SAT prep resource for K-12 students. Check out her Contently portfolio, follow her@madskillsvocab, or email her atmadison@anewdomain.net.