aNewDomain — Chogyam Trungpa writes about the heart warrior, the person who enacts peace through love and compassion.

aNewDomain — Chogyam Trungpa writes about the heart warrior, the person who enacts peace through love and compassion.

I’ve always had a problem with the warrior part of that idea. The Sacred Path of the Warrior is a beautiful treatise on the examined life, on the life of empathy and stillness, and it doesn’t deserve to be nit-picked. And yet …

I struggle to be peaceful.

This means I am peaceful as an aspiration more than as a matter of fact. But the attempt to be compassionate is not a war, and I am no warrior — spiritual or otherwise.

There are many alternative paths through life. I’ve chosen as peaceful a way as I can on mine. It’s helped to be large and clever.

Being large has opened a more peaceful path than might otherwise have been available. Being clever means I haven’t had to sell that size in service of violence.

And other perfectly decent people get pushed along other paths.

And other perfectly decent people get pushed along other paths.

How to accept death.

Sometimes, it isn’t possible or reasonable to accept death.

Denial of death is the only sensible recourse, as Ernest Becker pointed out in his brilliant book by the same name back in the 1970s.

First responders – police, firefighters, EMTs, others – experience the transient nature of life on a daily basis. All the chaos, unpredictability, impotence of life are evident and in their faces all the time. Body integrity becomes a serious concern for then. You really cannot ever forget that you are made of meat in this situation, can’t ever forget that there are people out there with knives, guns, cars. Disease. Fire. Smoke and unsound structures.

It’s relatively easy to accept death from a quiet place of contemplation. It’s going to happen, it’s inevitable. But for first responders, it isn’t inevitable only in the abstract sense. First responders hear every day about cops killed in the line of duty, patients lost, firefighters lost, first responders who “made the ultimate sacrifice.”

They never laid down their lives in a formal offering, like the Lion in Narnia. Instead they were nailed to a cross like Jesus.

In other words, the job comes with risks.

Accepting those risks is not the same as walking to the gallows proudly, head high, knowing your martyrdom is in service of something larger.

How can you be a soldier, a warrior, a first responder and, at the same time, operate from a place of inner stillness and peace.

It is possible. Really.

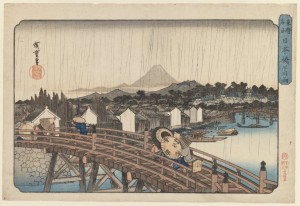

We could take, for example, the nihilistic style of Zen practice endemic to the Samurai of middle-ages Japan.

Reading Edo-period poetry gives us the impression of Samurai as sort of warrior-mystics, death-aware artists. You write your death-poem, accepting your end, then you have nothing to struggle for, nothing to lose: The battle occurs in the moment, free of complications and anxiety.

Trouble is, there wasn’t a lot of fighting left to be done by this period. The Edo period was so full of poems and paintings of flowers because all the warlords were confined to their fortresses or nailed down in Tokyo. Fighting was simply not permitted. The large-scale conflicts that dominated much of Japanese history were coming to a close.

If we examine the Samurai of the former periods before there was a solidly centralized government, when warlords contested for land and power, the Samurai weren’t actually such swell cats. They frequently changed sides, for example, for money or promotions or other favors. They didn’t, by and large, get formal educations and write poetry: they cut off each other’s heads to present to their lords for payment.

A substantial percentage of our first responders are diagnosable with post traumatic stress disorder. Many never seek diagnosis or treatment. The stress of the work is frequently evident in private lives – divorces, alcohol use, other problematic behavior. People get into fitness, health food, whatever it takes to tell themselves they can live forever.

For such people, a Bushido-style code of honor and obligation might not be terribly helpful. Accepting death is harder than denying it when it is real, in your face, every day. Doing so doesn’t necessarily make you a great person. It takes your beautiful philosophy and makes it nihilistic.

This is ultimately my problem with Trungpa: The words are wise and the ideals beautiful, but ultimately this philosophy is unrealistic for actual warriors.

The warrior does two things. First, he kills the enemy. Second, he protects his friends.

When I was in satellite operations, someone on my unit tried to say we were warriors. I was willing to hear an argument, but another colleague pointed to our flight commander, a Major who had transferred in from an F-16 unit. Ex-pilot. He said, read this, and handed us the write-up from his own highest medal. It was full of jargon about saving money, managing a difficult technical problem as part of a team. Then he said, “The Major has a bronze star. Want to hear what the write-up says? It says he killed [x number] of the enemy in combat.”

To this day I feel silly when someone calls me a veteran or, worse yet, thanks me for my service. I didn’t give that – in the end, I never directly sacrificed my clean hands for you.

I never killed someone.

I’m not a warrior. Not a soldier, not a killer. I’m out of the first-response business, too, if you can call psychiatric hospital work part of that endeavor – and I’ve run down enough hallways to rescue colleagues on other units that I’ll hear your argument. My partner there always said we were warriors, too, and I know what he meant: We had to show up to this violent place, work empathetically with people with violent minds and violent histories, sometimes defend ourselves and each other physically.

But it was never a war.

I couldn’t deny death there. It was in my face, all the time. I saw patients die no matter how they struggled to live, dying of their habits or their medications or simple old age. I was throttled nearly out by a guy who trained all the time, every day so that when the chance came, he could kill one of us.

Chance saved my life.

First responders face it every day, and they can’t be Samurai. We wouldn’t like that very much. When we see racial violence enacted by cops, we’re dangerously close to the Samurai ethic already: unquestioned authority to enact any whim up to and including murder. With impunity.

Where does that leave us?

Maybe with damage reduction. Denial of death can come in large or small packages. It can be scapegoating, nationalism, destiny – the Third Reich.

Or it can be shaving your legs and taking up cycling. Cooking. Programming. Going on a gluten-free diet.

Hey, it might be silly, but the worst thing a gluten-free diet is going to do to you is cost you more money at Whole Paycheck.

Sometimes, you must deny death. But you remain a free agent in the world. If you do that, can you at least try to choose a benign means of doing so?

I’m Jason Dias for aNewDomain, and I’m still on the right side of the dirt.

Image one: “Narbonne – Musée Lapidaire – 20150110 (3)” by Olybrius – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Narbonne_-_Mus%C3%A9e_Lapidaire_-_20150110_(3).jpg#/media/File:Narbonne_-_Mus%C3%A9e_Lapidaire_-_20150110_(3).jpg; image two: “Brooklyn Museum – Evening Shower at Nihonbashi Bridge, from Celebrated Places in the Eastern Capital (Toto Meisho) – Utagawa Hiroshige (Ando) – overall” by Utagawa Hiroshige – Online Collection of Brooklyn Museum; Photo: Brooklyn Museum, 41.471_IMLS_PS3.jpg. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Brooklyn_Museum_-_Evening_Shower_at_Nihonbashi_Bridge,_from_Celebrated_Places_in_the_Eastern_Capital_(Toto_Meisho)_-_Utagawa_Hiroshige_(Ando)_-_overall.jpg#/media/File:Brooklyn_Museum,Evening_Shower_at_Nihonbashi_Bridge; image three: “Sacred turtle in China” by Paul Munhoven – Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons; image four: “General Dynamic F-16 USAF” by U.S. Air Force photo – http://www.af.mil/shared/media/photodb/photos/021105-O-9999G-056.jpg. Licensed under Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Cover image: Birdcage https://www.pinterest.com/javiernicolas/instalaciones-artisticas/